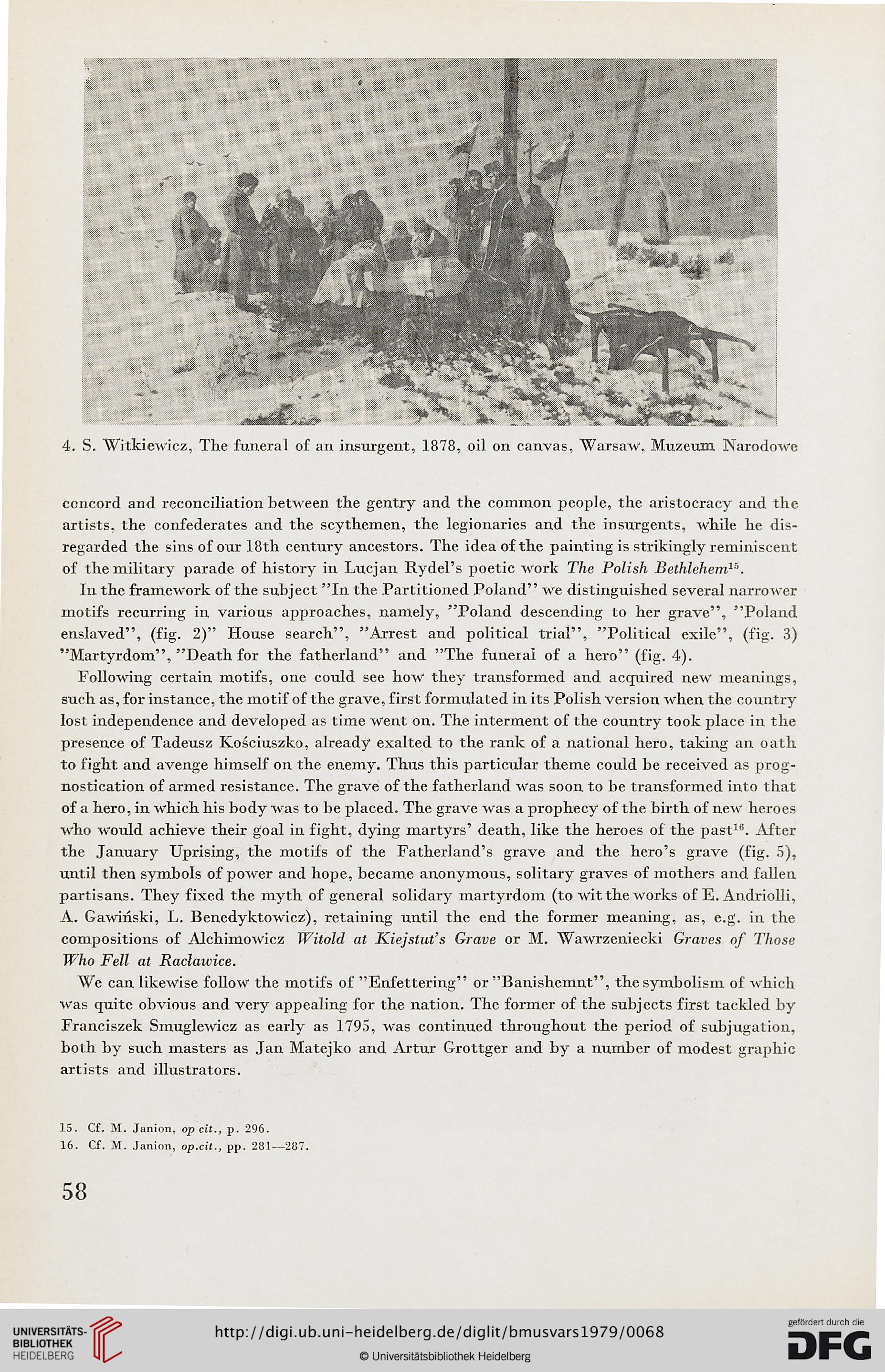

4. S. Witkiewicz, The funeral of an insurgent, 1878, oil on canvas, Warsaw, Muzeum Narodowe

ccncord and reconciliation between the gentry and the common people, the aristocracy and the

artists, the confederates and the scythemen, the legionaries and the insurgents, while he dis-

regarded the sins ofourl8th century ancestors. The idea of the painting is strikingly reminiscent

of themilitary paradę of history in Lucjan Rydel's poetic work The Polish Bełhlehem15.

In the framework of the subject "In the Partitioned Poland" we distinguished several narrower

motifs recurring in various approaches, namely, "Poland descending to her grave", "Poland

enslaved", (fig. 2)" House search", "Arrest and political trial", "Political exile", (fig. 3)

"Martyrdom", "Death for the fatherland" and "The funeral of a hero" (fig. 4).

Following certain motifs, one could see how they transformed and acquired new meanings,

such as, for instance, the motif of the grave, first formulated in its Polish version when the country

łost independence and deve!oped as time went on. The interment of the country took place in the

presence of Tadeusz Kościuszko, already exalted to the rank of a national hero, taking an oath

to fight and avenge himself on the enemy. Thus this particular theme could be received as prog-

nostication of armed resistance. The grave of the fatherland was soon to be transformed into that

of a hero, in which his body was to be placed. The grave was a prophecy of the birth of new heroes

who would achieve their goal in fight, dying martyrs' death, like the heroes of the pastlc. After

the January Uprising, the motifs of the Fatherland's grave and the hero's grave (fig. 5),

until then symbols of power and hope, became anonymous, solitary graves of mothers and fallen

partisans. They fixed the myth of generał solidary martyrdom (to wit the works of E. Andriolli,

A. Gawiński, L. Benedyktowicz), retaining until the end the former meaning, as, e.g. in the

compositions of Alchimowicz Witold at Kiejstufs Grave or M. Wawrzeniecki Graves of Those

Who Feli al Racławice.

We can likewise follow the motifs of "Enfettering" or "Banishemnt", thesymbolism of which

was ąuite obvious and very appealing for the nation. The former of the subjects first tackled by

Franciszek Smuglewicz as early as 1795, was continued throughout the period of subjugation,

both by such masters as Jan Matejko and Artur Grottger and by a number of modest graphic

artists and illustrators.

15. Cf. M. Janion, op cit., p. 296.

16. Cf. M. Janion, op.cit., pp. 281— 2U7.

58

ccncord and reconciliation between the gentry and the common people, the aristocracy and the

artists, the confederates and the scythemen, the legionaries and the insurgents, while he dis-

regarded the sins ofourl8th century ancestors. The idea of the painting is strikingly reminiscent

of themilitary paradę of history in Lucjan Rydel's poetic work The Polish Bełhlehem15.

In the framework of the subject "In the Partitioned Poland" we distinguished several narrower

motifs recurring in various approaches, namely, "Poland descending to her grave", "Poland

enslaved", (fig. 2)" House search", "Arrest and political trial", "Political exile", (fig. 3)

"Martyrdom", "Death for the fatherland" and "The funeral of a hero" (fig. 4).

Following certain motifs, one could see how they transformed and acquired new meanings,

such as, for instance, the motif of the grave, first formulated in its Polish version when the country

łost independence and deve!oped as time went on. The interment of the country took place in the

presence of Tadeusz Kościuszko, already exalted to the rank of a national hero, taking an oath

to fight and avenge himself on the enemy. Thus this particular theme could be received as prog-

nostication of armed resistance. The grave of the fatherland was soon to be transformed into that

of a hero, in which his body was to be placed. The grave was a prophecy of the birth of new heroes

who would achieve their goal in fight, dying martyrs' death, like the heroes of the pastlc. After

the January Uprising, the motifs of the Fatherland's grave and the hero's grave (fig. 5),

until then symbols of power and hope, became anonymous, solitary graves of mothers and fallen

partisans. They fixed the myth of generał solidary martyrdom (to wit the works of E. Andriolli,

A. Gawiński, L. Benedyktowicz), retaining until the end the former meaning, as, e.g. in the

compositions of Alchimowicz Witold at Kiejstufs Grave or M. Wawrzeniecki Graves of Those

Who Feli al Racławice.

We can likewise follow the motifs of "Enfettering" or "Banishemnt", thesymbolism of which

was ąuite obvious and very appealing for the nation. The former of the subjects first tackled by

Franciszek Smuglewicz as early as 1795, was continued throughout the period of subjugation,

both by such masters as Jan Matejko and Artur Grottger and by a number of modest graphic

artists and illustrators.

15. Cf. M. Janion, op cit., p. 296.

16. Cf. M. Janion, op.cit., pp. 281— 2U7.

58