Political ideas were carried most expressively in the representations of burials, closely related

to the images of death, graves and cemeteries. Such representations had had a very long tradition,

had been approached from a number of angles and inspired a wealth of interpretations. They

accaiired a political significance in the iconography of Polish fights for independence, sińce they

depicted funeral processions following the coffins of victims fallen in mass patriotic demon-

strations against the invaders. This trend was represented at the exhibition by Władysław Maje-

ranowski's painting The Burial of the Victims Fallen in 1848 (fig. 6) and a very rich iconographic

materiał connected with the funeral of f ive participants in the street manifestations in Warsaw

in 1861, prior to the January Uprising of 1863.

A subject closely linked with those of death, burials and cemeteries is orphanhood, approached

in a variety of ways and penetrating in this symbolic expression. The treatmcnt of the subject

is permeated by a mood of loneliness and desertion, a loss of something very dear and indispens-

able. Dozens of Polish painters and graphic artists produces compositions dedicated to the

tragic hero : an innocent orphan. Among the best known Works are the paintings by Kazimierz

Alchimowicz, Walery Eljasz, Artur Grottger, Alfred Wierusz-ICowalski, Antoni Kozakiewicz,

Henryk Pillatti, Aleksander Kotsis, Józef Szermentowski, Władysław Slewiński, and Stanisław

Wyspiański. Their compositions, whether they represent village orphans (e.g. the paintings of

Kotsis or Szermentow-ski) or orphans of the royal blood (e.g. the works of Walery Eliasz) cause

one to see a lonely, parentless child as the embodiment of our national lot, of the lot of a Pole

deprived of his fartherland. The children's eyes, however, are fuli of confidence growing from

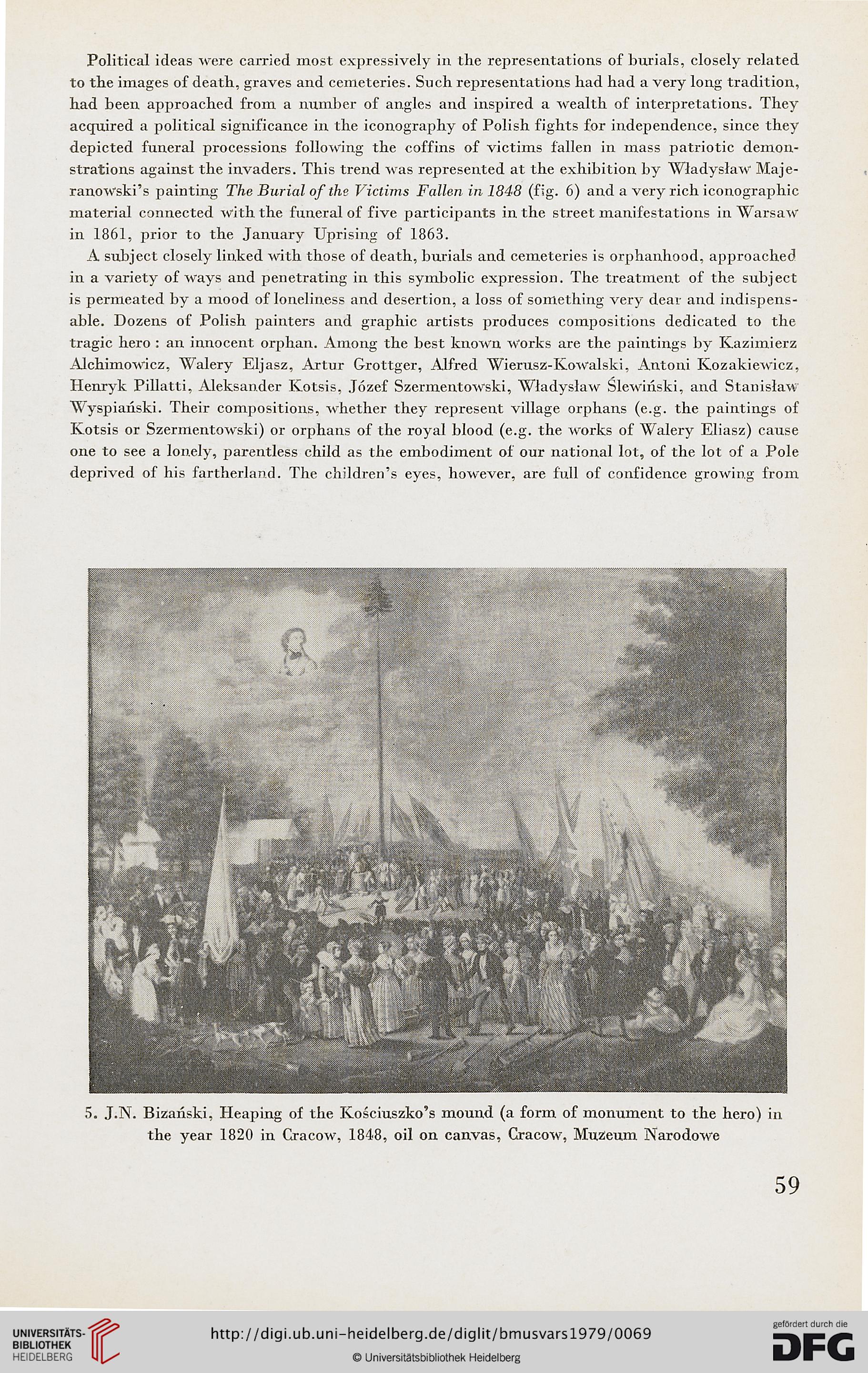

5. J.N. Bizański, Heaping of the Kościuszko's mound (a form of monument to the hero) in

the year 1820 in Gracow, 1848, oil on canvas, Cracow, Muzeum Narodowe

59

to the images of death, graves and cemeteries. Such representations had had a very long tradition,

had been approached from a number of angles and inspired a wealth of interpretations. They

accaiired a political significance in the iconography of Polish fights for independence, sińce they

depicted funeral processions following the coffins of victims fallen in mass patriotic demon-

strations against the invaders. This trend was represented at the exhibition by Władysław Maje-

ranowski's painting The Burial of the Victims Fallen in 1848 (fig. 6) and a very rich iconographic

materiał connected with the funeral of f ive participants in the street manifestations in Warsaw

in 1861, prior to the January Uprising of 1863.

A subject closely linked with those of death, burials and cemeteries is orphanhood, approached

in a variety of ways and penetrating in this symbolic expression. The treatmcnt of the subject

is permeated by a mood of loneliness and desertion, a loss of something very dear and indispens-

able. Dozens of Polish painters and graphic artists produces compositions dedicated to the

tragic hero : an innocent orphan. Among the best known Works are the paintings by Kazimierz

Alchimowicz, Walery Eljasz, Artur Grottger, Alfred Wierusz-ICowalski, Antoni Kozakiewicz,

Henryk Pillatti, Aleksander Kotsis, Józef Szermentowski, Władysław Slewiński, and Stanisław

Wyspiański. Their compositions, whether they represent village orphans (e.g. the paintings of

Kotsis or Szermentow-ski) or orphans of the royal blood (e.g. the works of Walery Eliasz) cause

one to see a lonely, parentless child as the embodiment of our national lot, of the lot of a Pole

deprived of his fartherland. The children's eyes, however, are fuli of confidence growing from

5. J.N. Bizański, Heaping of the Kościuszko's mound (a form of monument to the hero) in

the year 1820 in Gracow, 1848, oil on canvas, Cracow, Muzeum Narodowe

59