43

was to ensure a consistency of his subsequent directives

and decisions in the matters of art. Such an interpretation

of theoretical regulations contained in the Instructiones

seems to be confirmed by the actual deeds of Borromeo

who, during his episcopate in Milan, always collaborated

with Pellegrino Tibaldi (1527-1596), engaging him, for ex-

ample, to participate in teams conducting canonical visi-

tations. But, above all, he consistently commissioned him

to erect churches52 which, as attested by Giussano, served

as exemplary solutions which represented the church

types described in the decrees of the synod of 1565 and in

the Instructiones.53 It is impossible to determine the extent

of Tibaldis contribution in the latter work, but there can

be no doubt that, through his architectural work, he en-

sured the compatibility of the archbishops ‘theory of art’

with the actual products of his artistic patronage. There-

fore, it has been repeatedly emphasised in the literature

that, by permanently engaging this outstanding architect,

by making him familiar with the most intricate aspects of

sacred art, and by assuring him a very high standing in his

milieu, Borromeo indicated a successful model of achiev-

ing artistic solutions that strictly conformed to the needs

of the Church in the period of its renewal after the Coun-

cil of Trent.54 Significantly less attention has been devoted

to similar actions of prelates who, while trying to improve

the religious life in north-Italian dioceses in the first half

of the sixteenth century, resorted to comparable means in

order to deploy the talents of Giulio Romano (1499-1546)

in the effort of cementing their reforms.

52 S. Scotti, ‘L’architettura e riforma cattolica nella Milano di Carlo

Borromeo’, IlArte, 5, 1972, pp. 54-90; S. Della Torre, R. Scho-

lield, Pellegrino Tibaldi architetto e il San Fedele in Milano. In-

venzione e construzione di una chiesa essemplare, Milan, 1984,

passim-, J. Ackerman, ‘Pellegrino Tibaldi, san Carlo Borromeo

e l’architettura ecclesiastica di loro tempo’, in San Carlo e il suo

tempo, voi. 2, Rome, 1986, pp. 573-586; M.L. Gatti Perer, ‘Le

opere e i giorni. Pellegrino Pellegrini detto II Tibaldi e il rinnova-

mento dell’arte cristiana’, Arte Lombarda, serie nuova 93-94,1990,

pp. 7-11; R. Haslam, ‘Pellegrino Pellegrini, Carlo Borromeo and

Public Architecture of the Counter-Reformation’, ibidem, pp. 17-

-30; A. Rovetta, ‘Pellegrino Tibaldi e l’idea del Tempio San Se-

bastiano’, ibidem, pp. 105-110; D. Moor, Pellegrino Tibaldis Chur-

ch of San Fedele in Milan. The Jesuits, Carlo Borromeo and Reli-

gious Architecture of the Late Sixteenth Century, Ann Arbor, 1989,

passim-, J. Alexander, From Renaissance to Counter-Reforma-

tion, pp. 217-225 (as in note 6).

53 G.P. Giussano, Vita di S. Carlo Borromeo prete cardinale del tito-

lo di Santa Prassede arcivescovo di Milano, Rome, 1610, pp. 91-94,

624-629,471-472. See also A. Scotti Tosini, ‘La “bella maniera”:

architetti, committenti, teoria e forma dell’architettura tra Roma

e Milano nel Cinquecento’, in Lombardia manierista. Arti e archi-

tettura 1535-1600, ed. by M.T. Fiorio, V. Terrarob, Milan, 2009,

pp. 87-88.

54 Apart from the works cited in note 52, see in particular: E.C. Vo-

ELKER, ‘Borromeo’s Influence on Sacred Art and Architecture’, in

San Carlo Borromeo. Catholic Reform, pp. 122-187 (as in note 5).

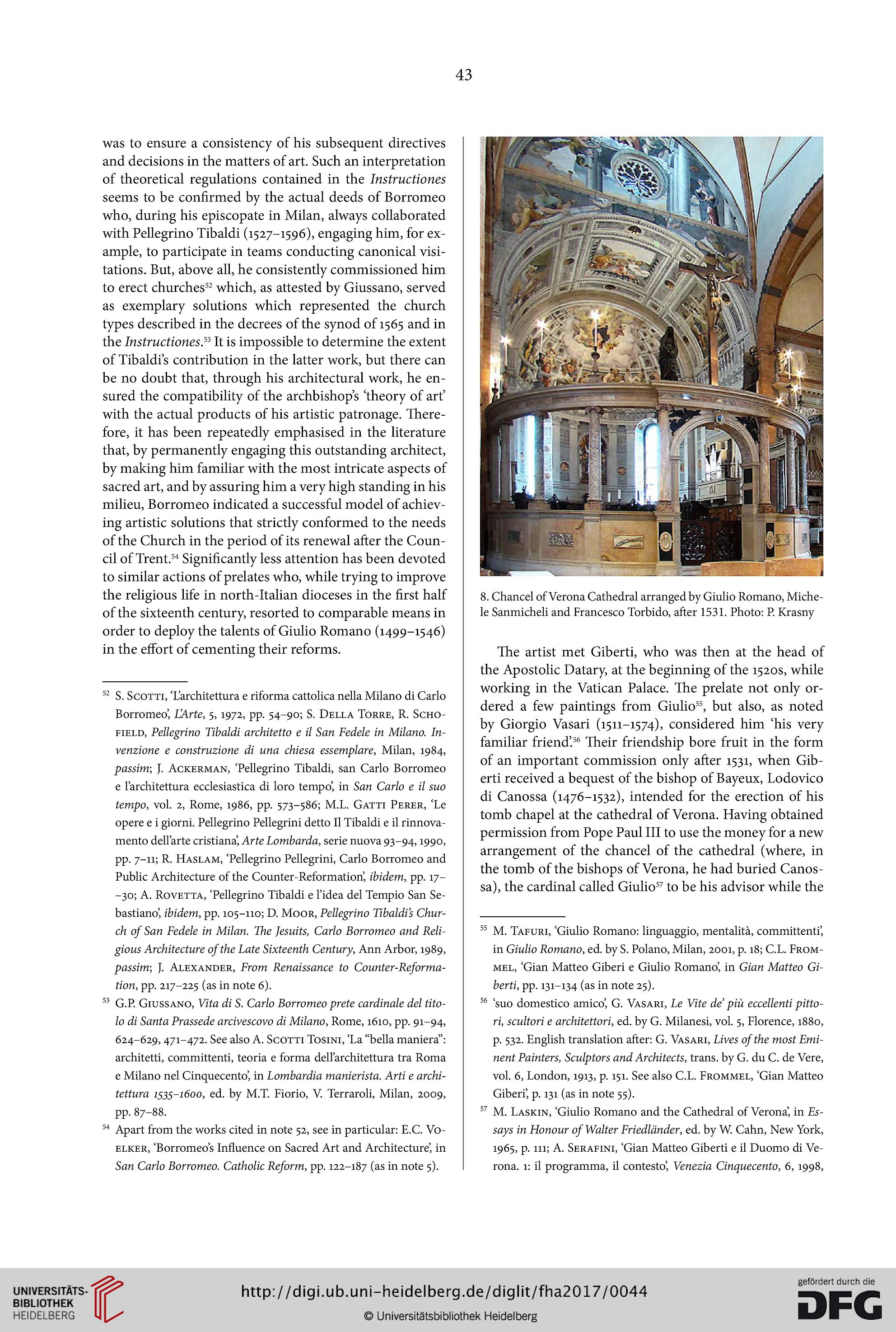

8. Chancel of Verona Cathedral arranged by Giulio Romano, Miche-

le Sanmicheli and Francesco Torbido, after 1531. Photo: P. Krasny

The artist met Giberti, who was then at the head of

the Apostolic Datary, at the beginning of the 1520s, while

working in the Vatican Palace. The prelate not only or-

dered a few paintings from Giulio55, but also, as noted

by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), considered him ‘his very

familiar friend’.56 Their friendship bore fruit in the form

of an important commission only after 1531, when Gib-

erti received a bequest of the bishop of Bayeux, Lodovico

di Canossa (1476-1532), intended for the erection of his

tomb chapel at the cathedral of Verona. Having obtained

permission from Pope Paul III to use the money for a new

arrangement of the chancel of the cathedral (where, in

the tomb of the bishops of Verona, he had buried Canos-

sa), the cardinal called Giulio57 to be his advisor while the

55 M. Tafuri, ‘Giulio Romano: linguaggio, mentalità, committenti’,

in Giulio Romano, ed. by S. Polano, Milan, 2001, p. 18; C.L. From-

mel, ‘Gian Matteo Giberi e Giulio Romano’, in Gian Matteo Gi-

berti, pp. 131-134 (as in note 25).

56 ‘suo domestico amico’, G. Vasari, Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pitto-

ri, scultori e architettori, ed. by G. Milanesi, voi. 5, Florence, 1880,

p. 532. English translation after: G. Vasari, Lives of the most Emi-

nent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans, by G. du C. de Vere,

vol. 6, London, 1913, p. 151. See also C.L. Frommel, ‘Gian Matteo

Giberi’, p. 131 (as in note 55).

57 M. Laskin, ‘Giulio Romano and the Cathedral of Verona’, in Es-

says in Honour of Walter Friedländer, ed. by W. Cahn, New York,

1965, p. 111; A. Serafini, ‘Gian Matteo Giberti e il Duomo di Ve-

rona. 1: il programma, il contesto’, Venezia Cinquecento, 6, 1998,

was to ensure a consistency of his subsequent directives

and decisions in the matters of art. Such an interpretation

of theoretical regulations contained in the Instructiones

seems to be confirmed by the actual deeds of Borromeo

who, during his episcopate in Milan, always collaborated

with Pellegrino Tibaldi (1527-1596), engaging him, for ex-

ample, to participate in teams conducting canonical visi-

tations. But, above all, he consistently commissioned him

to erect churches52 which, as attested by Giussano, served

as exemplary solutions which represented the church

types described in the decrees of the synod of 1565 and in

the Instructiones.53 It is impossible to determine the extent

of Tibaldis contribution in the latter work, but there can

be no doubt that, through his architectural work, he en-

sured the compatibility of the archbishops ‘theory of art’

with the actual products of his artistic patronage. There-

fore, it has been repeatedly emphasised in the literature

that, by permanently engaging this outstanding architect,

by making him familiar with the most intricate aspects of

sacred art, and by assuring him a very high standing in his

milieu, Borromeo indicated a successful model of achiev-

ing artistic solutions that strictly conformed to the needs

of the Church in the period of its renewal after the Coun-

cil of Trent.54 Significantly less attention has been devoted

to similar actions of prelates who, while trying to improve

the religious life in north-Italian dioceses in the first half

of the sixteenth century, resorted to comparable means in

order to deploy the talents of Giulio Romano (1499-1546)

in the effort of cementing their reforms.

52 S. Scotti, ‘L’architettura e riforma cattolica nella Milano di Carlo

Borromeo’, IlArte, 5, 1972, pp. 54-90; S. Della Torre, R. Scho-

lield, Pellegrino Tibaldi architetto e il San Fedele in Milano. In-

venzione e construzione di una chiesa essemplare, Milan, 1984,

passim-, J. Ackerman, ‘Pellegrino Tibaldi, san Carlo Borromeo

e l’architettura ecclesiastica di loro tempo’, in San Carlo e il suo

tempo, voi. 2, Rome, 1986, pp. 573-586; M.L. Gatti Perer, ‘Le

opere e i giorni. Pellegrino Pellegrini detto II Tibaldi e il rinnova-

mento dell’arte cristiana’, Arte Lombarda, serie nuova 93-94,1990,

pp. 7-11; R. Haslam, ‘Pellegrino Pellegrini, Carlo Borromeo and

Public Architecture of the Counter-Reformation’, ibidem, pp. 17-

-30; A. Rovetta, ‘Pellegrino Tibaldi e l’idea del Tempio San Se-

bastiano’, ibidem, pp. 105-110; D. Moor, Pellegrino Tibaldis Chur-

ch of San Fedele in Milan. The Jesuits, Carlo Borromeo and Reli-

gious Architecture of the Late Sixteenth Century, Ann Arbor, 1989,

passim-, J. Alexander, From Renaissance to Counter-Reforma-

tion, pp. 217-225 (as in note 6).

53 G.P. Giussano, Vita di S. Carlo Borromeo prete cardinale del tito-

lo di Santa Prassede arcivescovo di Milano, Rome, 1610, pp. 91-94,

624-629,471-472. See also A. Scotti Tosini, ‘La “bella maniera”:

architetti, committenti, teoria e forma dell’architettura tra Roma

e Milano nel Cinquecento’, in Lombardia manierista. Arti e archi-

tettura 1535-1600, ed. by M.T. Fiorio, V. Terrarob, Milan, 2009,

pp. 87-88.

54 Apart from the works cited in note 52, see in particular: E.C. Vo-

ELKER, ‘Borromeo’s Influence on Sacred Art and Architecture’, in

San Carlo Borromeo. Catholic Reform, pp. 122-187 (as in note 5).

8. Chancel of Verona Cathedral arranged by Giulio Romano, Miche-

le Sanmicheli and Francesco Torbido, after 1531. Photo: P. Krasny

The artist met Giberti, who was then at the head of

the Apostolic Datary, at the beginning of the 1520s, while

working in the Vatican Palace. The prelate not only or-

dered a few paintings from Giulio55, but also, as noted

by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), considered him ‘his very

familiar friend’.56 Their friendship bore fruit in the form

of an important commission only after 1531, when Gib-

erti received a bequest of the bishop of Bayeux, Lodovico

di Canossa (1476-1532), intended for the erection of his

tomb chapel at the cathedral of Verona. Having obtained

permission from Pope Paul III to use the money for a new

arrangement of the chancel of the cathedral (where, in

the tomb of the bishops of Verona, he had buried Canos-

sa), the cardinal called Giulio57 to be his advisor while the

55 M. Tafuri, ‘Giulio Romano: linguaggio, mentalità, committenti’,

in Giulio Romano, ed. by S. Polano, Milan, 2001, p. 18; C.L. From-

mel, ‘Gian Matteo Giberi e Giulio Romano’, in Gian Matteo Gi-

berti, pp. 131-134 (as in note 25).

56 ‘suo domestico amico’, G. Vasari, Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pitto-

ri, scultori e architettori, ed. by G. Milanesi, voi. 5, Florence, 1880,

p. 532. English translation after: G. Vasari, Lives of the most Emi-

nent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans, by G. du C. de Vere,

vol. 6, London, 1913, p. 151. See also C.L. Frommel, ‘Gian Matteo

Giberi’, p. 131 (as in note 55).

57 M. Laskin, ‘Giulio Romano and the Cathedral of Verona’, in Es-

says in Honour of Walter Friedländer, ed. by W. Cahn, New York,

1965, p. 111; A. Serafini, ‘Gian Matteo Giberti e il Duomo di Ve-

rona. 1: il programma, il contesto’, Venezia Cinquecento, 6, 1998,