129

boots, holding a book in his hands.11 Such a distinctly dig-

nified likeness of the Reformer was further validated by

his tomb monuments: a memorial brass (which made its

way to the university church in Jena) and a painted me-

morial portrait in the Castle Church in Wittenberg.12

But, as stated by Treu, the key role in the dissemination

of images of this type was played by a woodcut executed

by Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-1586) around 1560

[Fig. 1].13 The heroic aspect of this representation, empha-

sised by the arcade framing Luthers figure in the wood-

cut, contributed to the fact that it was repeated in numer-

ous monuments to the theologian14, and recently also in

a plastic figurine, included in a set of the Playmobil toys

manufactured by the Geobra Brandstätter company on

the occasion of the Reformation jubilee.15

Protestant theologians proclaimed unanimously that

Luther in his lifetime was a device in Gods hands, and

was used by the Almighty to renovate the Church.16 This

conviction had led them to employ, after Luthers death,

his appropriately devised image to corroborate and dis-

seminate the reform initiated by him. Thus, by appropria-

tely exhibiting his chosen traits or underscoring such of

his actions that in the best way supported the ‘propagan-

dists line’ of the new confession, he was soon turned into

an elusive mythical figure’ or ‘the Luther of historians’.

The Catholics responded by exaggerating the vices and

misconducts of the Reformer.17 Such a narration of Luther

was particularly conspicuous in artworks, in which - be-

cause of the medium’s inherent quality of condensing the

message it conveyed - the content could not be attenu-

ated, even by means of smallest nuances, as it sometimes

Christo Soteri veritati.

TaaBww dtfbJ'cr , Кпсг^ыт-

VINDICI tLVCIS EVANGELICA. R EST I TV TORI,

'w сЧг. Tier JICax. lUtufa per Çftnw*: «xrf*urnt-i

rf—•£.. - il-__ J... f <■ wii

ТЛ VOCE proclamant

llWbif natus, Éipcns 4Uixpić rcòJitus oris.

Convelli* tumidi regna, LVTHERE,Paox

Pofte m fi laudi bené dogma Iccuta fuilsct

furba Ducis, iam mi fraus um,Roma,foret

vH -ut.u i ,

fcmjfeWKW à

fj wffïrfira Т11плш1*1{|у

tu Fl Airn ГК

tÄl fviVvnfi Двпя

VvT-.JAiarnI Cv 16

mVrrùi $aViwT».rr N#

J иииие rftüprttnoMmna .mdt

' lu. ‘ : t

£îi.fimi*wl4il;iirVnf WM«»)*': i

ЙяЯ ОД«£ыг№£ап*{<фпд>.

TuAm’wk&ibi (г44П01->1 СхН > .

OïaA;piin4Ti5abTTtAirit',rvv6n

CV,-ery u rtn

ÇW nvtl :Л1НИ| CfmfÏMléml*

£rtuie*n .

vrpffun ««iWmWrKifStKl

iZmtvnfAlU* tu,fi Anit Ąrtf. '

">vj WibrC* vitia bi frît

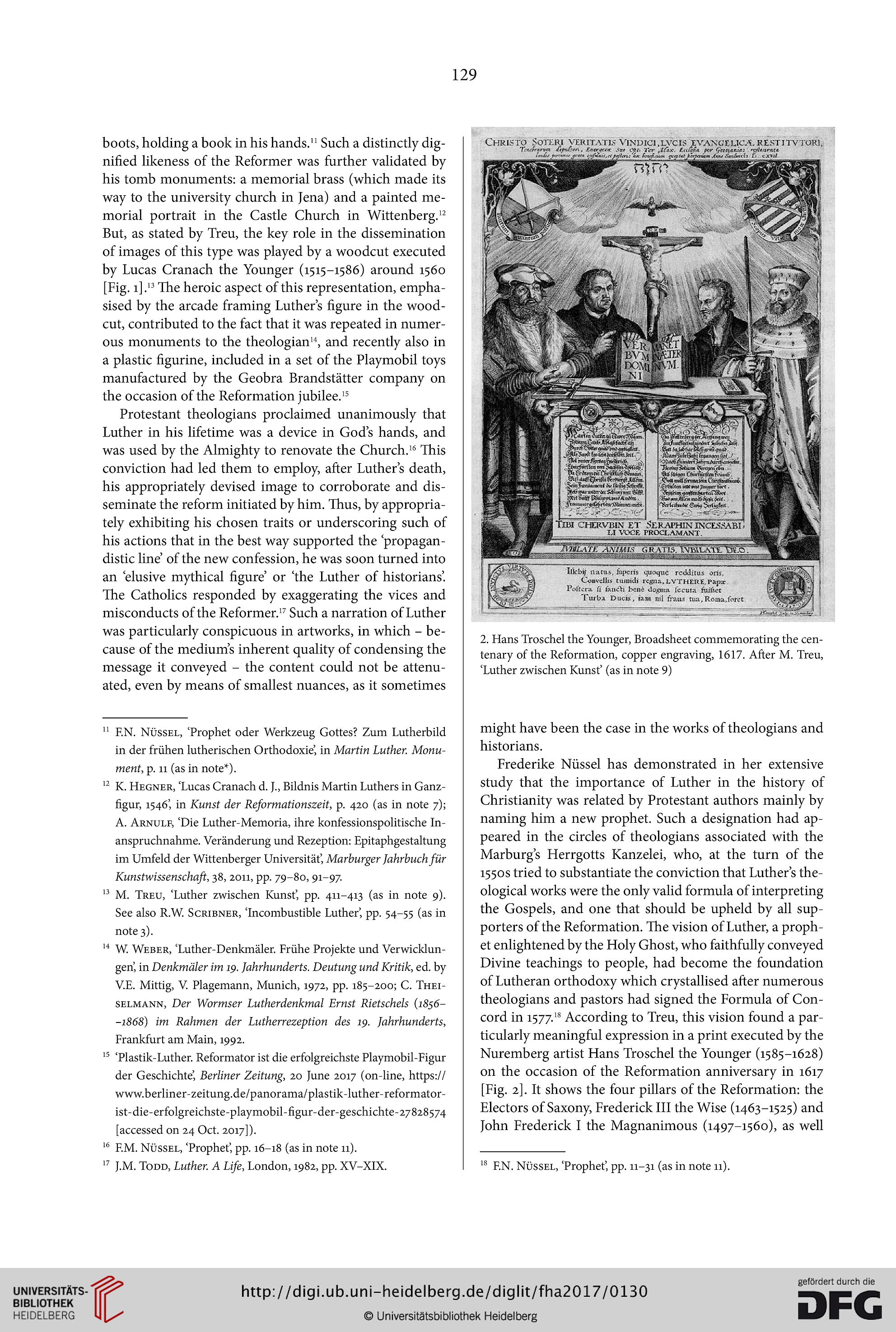

2. Hans Troschel the Younger, Broadsheet commemorating the cen-

tenary of the Reformation, copper engraving, 1617. After M. Treu,

‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as in note 9)

11 F.N. Nüssel, ‘Prophet oder Werkzeug Gottes? Zum Lutherbild

in der frühen lutherischen Orthodoxie’, in Martin Luther. Monu-

ment, p. 11 (as in note*).

12 K. Hegner, ‘Lucas Cranach d. J., Bildnis Martin Luthers in Ganz-

figur, 1546’, in Kunst der Reformationszeit, p. 420 (as in note 7);

A. Arnulf, ‘Die Luther-Memoria, ihre konfessionspolitische In-

anspruchnahme. Veränderung und Rezeption: Epitaphgestaltung

im Umfeld der Wittenberger Universität’, Marburger Jahrbuch für

Kunstwissenschaft, 38, 2011, pp. 79-80, 91-97.

13 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 411-413 (as in note 9).

See also R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, pp. 54-55 (as in

note 3).

14 W. Weber, ‘Luther-Denkmäler. Frühe Projekte und Verwicklun-

gen, in Denkmäler im 19. Jahrhunderts. Deutung und Kritik, ed. by

VE. Mittig, V. Plagemann, Munich, 1972, pp. 185-200; C. Thei-

selmann, Der Wormser Lutherdenkmal Ernst Rietschels (1856-

-1868) im Rahmen der Lutherrezeption des 19. Jahrhunderts,

Frankfurt am Main, 1992.

15 ‘Plastik-Luther. Reformator ist die erfolgreichste Playmobil-Figur

der Geschichte’, Berliner Zeitung, 20 June 2017 (on-line, https://

www.berliner-zeitung.de/panorama/plastik-luther-reformator-

ist-die-erfolgreichste-playmobil-figur-der-geschichte-27828574

[accessed on 24 Oct. 2017]).

16 F.M. Nüssel, ‘Prophet’, pp. 16-18 (as in note 11).

17 J.M. Todd, Luther. A Life, London, 1982, pp. XV-XIX.

might have been the case in the works of theologians and

historians.

Frederike Nüssel has demonstrated in her extensive

study that the importance of Luther in the history of

Christianity was related by Protestant authors mainly by

naming him a new prophet. Such a designation had ap-

peared in the circles of theologians associated with the

Marburg’s Herrgotts Kanzelei, who, at the turn of the

1550S tried to substantiate the conviction that Luther’s the-

ological works were the only valid formula of interpreting

the Gospels, and one that should be upheld by all sup-

porters of the Reformation. The vision of Luther, a proph-

et enlightened by the Holy Ghost, who faithfully conveyed

Divine teachings to people, had become the foundation

of Lutheran orthodoxy which crystallised after numerous

theologians and pastors had signed the Formula of Con-

cord in 15 77.18 According to Treu, this vision found a par-

ticularly meaningful expression in a print executed by the

Nuremberg artist Hans Troschel the Younger (1585-1628)

on the occasion of the Reformation anniversary in 1617

[Fig. 2]. It shows the four pillars of the Reformation: the

Electors of Saxony, Frederick III the Wise (1463-1525) and

John Frederick I the Magnanimous (1497-1560), as well

18 F.N. Nüssel, ‘Prophet’, pp. 11-31 (as in note 11).

boots, holding a book in his hands.11 Such a distinctly dig-

nified likeness of the Reformer was further validated by

his tomb monuments: a memorial brass (which made its

way to the university church in Jena) and a painted me-

morial portrait in the Castle Church in Wittenberg.12

But, as stated by Treu, the key role in the dissemination

of images of this type was played by a woodcut executed

by Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-1586) around 1560

[Fig. 1].13 The heroic aspect of this representation, empha-

sised by the arcade framing Luthers figure in the wood-

cut, contributed to the fact that it was repeated in numer-

ous monuments to the theologian14, and recently also in

a plastic figurine, included in a set of the Playmobil toys

manufactured by the Geobra Brandstätter company on

the occasion of the Reformation jubilee.15

Protestant theologians proclaimed unanimously that

Luther in his lifetime was a device in Gods hands, and

was used by the Almighty to renovate the Church.16 This

conviction had led them to employ, after Luthers death,

his appropriately devised image to corroborate and dis-

seminate the reform initiated by him. Thus, by appropria-

tely exhibiting his chosen traits or underscoring such of

his actions that in the best way supported the ‘propagan-

dists line’ of the new confession, he was soon turned into

an elusive mythical figure’ or ‘the Luther of historians’.

The Catholics responded by exaggerating the vices and

misconducts of the Reformer.17 Such a narration of Luther

was particularly conspicuous in artworks, in which - be-

cause of the medium’s inherent quality of condensing the

message it conveyed - the content could not be attenu-

ated, even by means of smallest nuances, as it sometimes

Christo Soteri veritati.

TaaBww dtfbJ'cr , Кпсг^ыт-

VINDICI tLVCIS EVANGELICA. R EST I TV TORI,

'w сЧг. Tier JICax. lUtufa per Çftnw*: «xrf*urnt-i

rf—•£.. - il-__ J... f <■ wii

ТЛ VOCE proclamant

llWbif natus, Éipcns 4Uixpić rcòJitus oris.

Convelli* tumidi regna, LVTHERE,Paox

Pofte m fi laudi bené dogma Iccuta fuilsct

furba Ducis, iam mi fraus um,Roma,foret

vH -ut.u i ,

fcmjfeWKW à

fj wffïrfira Т11плш1*1{|у

tu Fl Airn ГК

tÄl fviVvnfi Двпя

VvT-.JAiarnI Cv 16

mVrrùi $aViwT».rr N#

J иииие rftüprttnoMmna .mdt

' lu. ‘ : t

£îi.fimi*wl4il;iirVnf WM«»)*': i

ЙяЯ ОД«£ыг№£ап*{<фпд>.

TuAm’wk&ibi (г44П01->1 СхН > .

OïaA;piin4Ti5abTTtAirit',rvv6n

CV,-ery u rtn

ÇW nvtl :Л1НИ| CfmfÏMléml*

£rtuie*n .

vrpffun ««iWmWrKifStKl

iZmtvnfAlU* tu,fi Anit Ąrtf. '

">vj WibrC* vitia bi frît

2. Hans Troschel the Younger, Broadsheet commemorating the cen-

tenary of the Reformation, copper engraving, 1617. After M. Treu,

‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as in note 9)

11 F.N. Nüssel, ‘Prophet oder Werkzeug Gottes? Zum Lutherbild

in der frühen lutherischen Orthodoxie’, in Martin Luther. Monu-

ment, p. 11 (as in note*).

12 K. Hegner, ‘Lucas Cranach d. J., Bildnis Martin Luthers in Ganz-

figur, 1546’, in Kunst der Reformationszeit, p. 420 (as in note 7);

A. Arnulf, ‘Die Luther-Memoria, ihre konfessionspolitische In-

anspruchnahme. Veränderung und Rezeption: Epitaphgestaltung

im Umfeld der Wittenberger Universität’, Marburger Jahrbuch für

Kunstwissenschaft, 38, 2011, pp. 79-80, 91-97.

13 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 411-413 (as in note 9).

See also R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, pp. 54-55 (as in

note 3).

14 W. Weber, ‘Luther-Denkmäler. Frühe Projekte und Verwicklun-

gen, in Denkmäler im 19. Jahrhunderts. Deutung und Kritik, ed. by

VE. Mittig, V. Plagemann, Munich, 1972, pp. 185-200; C. Thei-

selmann, Der Wormser Lutherdenkmal Ernst Rietschels (1856-

-1868) im Rahmen der Lutherrezeption des 19. Jahrhunderts,

Frankfurt am Main, 1992.

15 ‘Plastik-Luther. Reformator ist die erfolgreichste Playmobil-Figur

der Geschichte’, Berliner Zeitung, 20 June 2017 (on-line, https://

www.berliner-zeitung.de/panorama/plastik-luther-reformator-

ist-die-erfolgreichste-playmobil-figur-der-geschichte-27828574

[accessed on 24 Oct. 2017]).

16 F.M. Nüssel, ‘Prophet’, pp. 16-18 (as in note 11).

17 J.M. Todd, Luther. A Life, London, 1982, pp. XV-XIX.

might have been the case in the works of theologians and

historians.

Frederike Nüssel has demonstrated in her extensive

study that the importance of Luther in the history of

Christianity was related by Protestant authors mainly by

naming him a new prophet. Such a designation had ap-

peared in the circles of theologians associated with the

Marburg’s Herrgotts Kanzelei, who, at the turn of the

1550S tried to substantiate the conviction that Luther’s the-

ological works were the only valid formula of interpreting

the Gospels, and one that should be upheld by all sup-

porters of the Reformation. The vision of Luther, a proph-

et enlightened by the Holy Ghost, who faithfully conveyed

Divine teachings to people, had become the foundation

of Lutheran orthodoxy which crystallised after numerous

theologians and pastors had signed the Formula of Con-

cord in 15 77.18 According to Treu, this vision found a par-

ticularly meaningful expression in a print executed by the

Nuremberg artist Hans Troschel the Younger (1585-1628)

on the occasion of the Reformation anniversary in 1617

[Fig. 2]. It shows the four pillars of the Reformation: the

Electors of Saxony, Frederick III the Wise (1463-1525) and

John Frederick I the Magnanimous (1497-1560), as well

18 F.N. Nüssel, ‘Prophet’, pp. 11-31 (as in note 11).