132

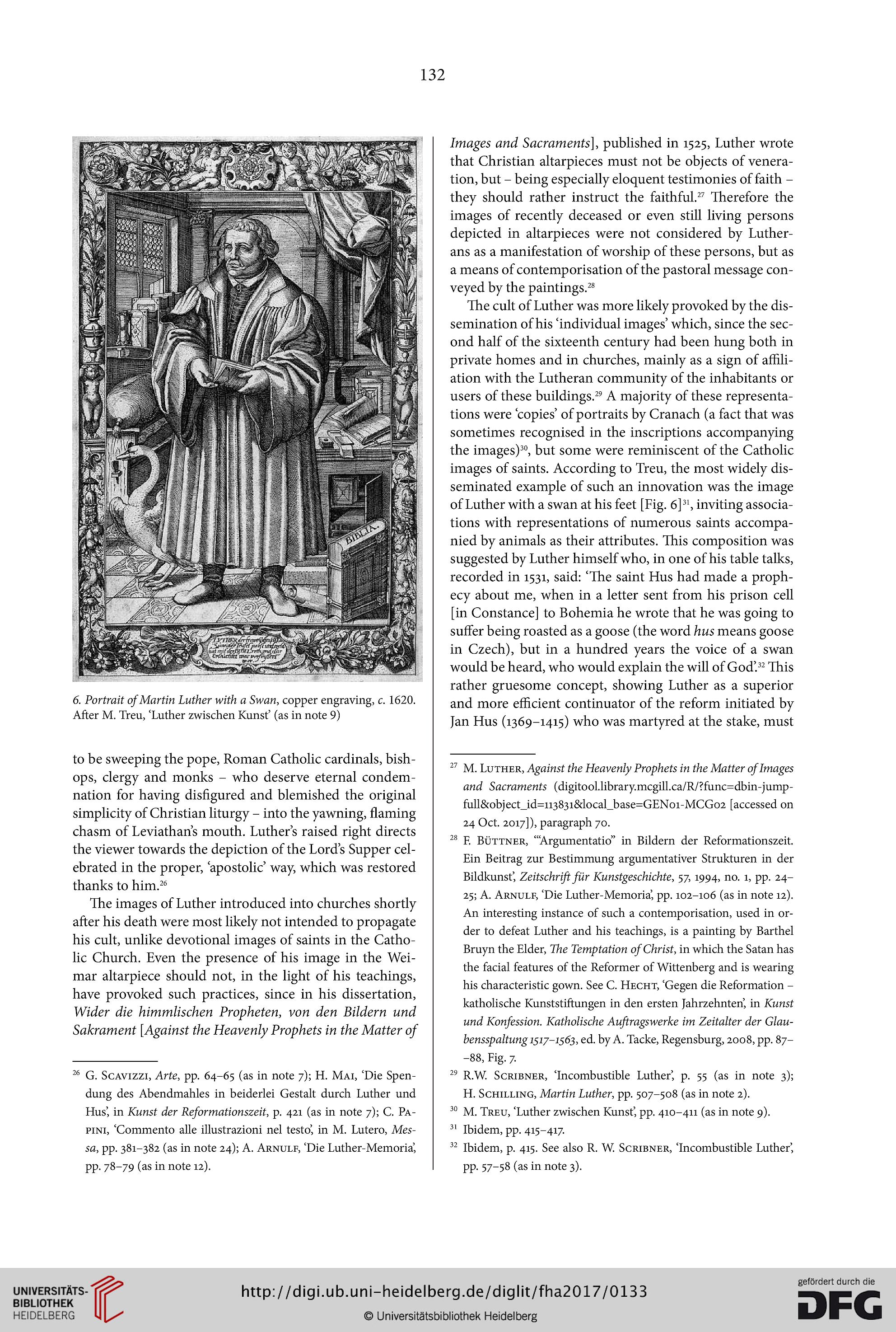

6. Portrait of Martin Luther with a Swan, copper engraving, c. 1620.

After M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as in note 9)

to be sweeping the pope, Roman Catholic cardinals, bish-

ops, clergy and monks - who deserve eternal condem-

nation for having disfigured and blemished the original

simplicity of Christian liturgy - into the yawning, flaming

chasm of Leviathans mouth. Luther’s raised right directs

the viewer towards the depiction of the Lords Supper cel-

ebrated in the proper, apostolic’ way, which was restored

thanks to him.26

The images of Luther introduced into churches shortly

after his death were most likely not intended to propagate

his cult, unlike devotional images of saints in the Catho-

lic Church. Even the presence of his image in the Wei-

mar altarpiece should not, in the light of his teachings,

have provoked such practices, since in his dissertation,

Wider die himmlischen Propheten, von den Bildern und

Sakrament [Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of

26 G. Soavizzi, Arte, pp. 64-65 (as in note 7); H. Mai, ‘Die Spen-

dung des Abendmahles in beiderlei Gestalt durch Luther und

Hus’, in Kunst der Reformationszeit, p. 421 (as in note 7); С. Pa-

piNi, ‘Commento alle illustrazioni nel testo’, in M. Lutero, Mes-

sa, pp. 381-382 (as in note 24); A. Arnulf, ‘Die Luther-Memoria’,

pp. 78-79 (as in note 12).

Images and Sacraments], published in 1525, Luther wrote

that Christian altarpieces must not be objects of venera-

tion, but - being especially eloquent testimonies of faith -

they should rather instruct the faithful.27 Therefore the

images of recently deceased or even still living persons

depicted in altarpieces were not considered by Luther-

ans as a manifestation of worship of these persons, but as

a means of contemporisation of the pastoral message con-

veyed by the paintings.28

The cult of Luther was more likely provoked by the dis-

semination of his ‘individual images’ which, since the sec-

ond half of the sixteenth century had been hung both in

private homes and in churches, mainly as a sign of affili-

ation with the Lutheran community of the inhabitants or

users of these buildings.29 A majority of these representa-

tions were copies’ of portraits by Cranach (a fact that was

sometimes recognised in the inscriptions accompanying

the images)30, but some were reminiscent of the Catholic

images of saints. According to Treu, the most widely dis-

seminated example of such an innovation was the image

of Luther with a swan at his feet [Fig. 6]31, inviting associa-

tions with representations of numerous saints accompa-

nied by animals as their attributes. This composition was

suggested by Luther himself who, in one of his table talks,

recorded in 1531, said: ‘The saint Hus had made a proph-

ecy about me, when in a letter sent from his prison cell

[in Constance] to Bohemia he wrote that he was going to

suffer being roasted as a goose (the word hus means goose

in Czech), but in a hundred years the voice of a swan

would be heard, who would explain the will of God’.32 This

rather gruesome concept, showing Luther as a superior

and more efficient continuator of the reform initiated by

Jan Hus (1369-1415) who was martyred at the stake, must

27 M. Luther, Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images

and Sacraments (digitool.library.mcgill.ca/R/?func=dbin-jump-

full&object_id=ii383i&local_base=GENoi-MCGo2 [accessed on

24 Oct. 2017]), paragraph 70.

28 F. Büttner, ‘“Argumentatio” in Bildern der Reformationszeit.

Ein Beitrag zur Bestimmung argumentativer Strukturen in der

Bildkunst’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 57, 1994, no. 1, pp. 24-

25; A. Arnulf, ‘Die Luther-Memoria’, pp. 102-106 (as in note 12).

An interesting instance of such a contemporisation, used in or-

der to defeat Luther and his teachings, is a painting by Barthel

Bruyn the Elder, The Temptation of Christ, in which the Satan has

the facial features of the Reformer of Wittenberg and is wearing

his characteristic gown. See C. Hecht, ‘Gegen die Reformation -

katholische Kunststiftungen in den ersten Jahrzehnten, in Kunst

und Konfession. Katholische Auftragswerke im Zeitalter der Glau-

bensspaltung 1517-1563, ed. by A. Tacke, Regensburg, 2008, pp. 87-

-88, Fig. 7.

29 R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, p. 55 (as in note 3);

H. Schilling, Martin Luther, pp. 507-508 (as in note 2).

30 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 410-411 (as in note 9).

31 Ibidem, pp. 415-417.

32 Ibidem, p. 415. See also R. W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’,

PP- 57-58 (as in note 3).

6. Portrait of Martin Luther with a Swan, copper engraving, c. 1620.

After M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as in note 9)

to be sweeping the pope, Roman Catholic cardinals, bish-

ops, clergy and monks - who deserve eternal condem-

nation for having disfigured and blemished the original

simplicity of Christian liturgy - into the yawning, flaming

chasm of Leviathans mouth. Luther’s raised right directs

the viewer towards the depiction of the Lords Supper cel-

ebrated in the proper, apostolic’ way, which was restored

thanks to him.26

The images of Luther introduced into churches shortly

after his death were most likely not intended to propagate

his cult, unlike devotional images of saints in the Catho-

lic Church. Even the presence of his image in the Wei-

mar altarpiece should not, in the light of his teachings,

have provoked such practices, since in his dissertation,

Wider die himmlischen Propheten, von den Bildern und

Sakrament [Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of

26 G. Soavizzi, Arte, pp. 64-65 (as in note 7); H. Mai, ‘Die Spen-

dung des Abendmahles in beiderlei Gestalt durch Luther und

Hus’, in Kunst der Reformationszeit, p. 421 (as in note 7); С. Pa-

piNi, ‘Commento alle illustrazioni nel testo’, in M. Lutero, Mes-

sa, pp. 381-382 (as in note 24); A. Arnulf, ‘Die Luther-Memoria’,

pp. 78-79 (as in note 12).

Images and Sacraments], published in 1525, Luther wrote

that Christian altarpieces must not be objects of venera-

tion, but - being especially eloquent testimonies of faith -

they should rather instruct the faithful.27 Therefore the

images of recently deceased or even still living persons

depicted in altarpieces were not considered by Luther-

ans as a manifestation of worship of these persons, but as

a means of contemporisation of the pastoral message con-

veyed by the paintings.28

The cult of Luther was more likely provoked by the dis-

semination of his ‘individual images’ which, since the sec-

ond half of the sixteenth century had been hung both in

private homes and in churches, mainly as a sign of affili-

ation with the Lutheran community of the inhabitants or

users of these buildings.29 A majority of these representa-

tions were copies’ of portraits by Cranach (a fact that was

sometimes recognised in the inscriptions accompanying

the images)30, but some were reminiscent of the Catholic

images of saints. According to Treu, the most widely dis-

seminated example of such an innovation was the image

of Luther with a swan at his feet [Fig. 6]31, inviting associa-

tions with representations of numerous saints accompa-

nied by animals as their attributes. This composition was

suggested by Luther himself who, in one of his table talks,

recorded in 1531, said: ‘The saint Hus had made a proph-

ecy about me, when in a letter sent from his prison cell

[in Constance] to Bohemia he wrote that he was going to

suffer being roasted as a goose (the word hus means goose

in Czech), but in a hundred years the voice of a swan

would be heard, who would explain the will of God’.32 This

rather gruesome concept, showing Luther as a superior

and more efficient continuator of the reform initiated by

Jan Hus (1369-1415) who was martyred at the stake, must

27 M. Luther, Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images

and Sacraments (digitool.library.mcgill.ca/R/?func=dbin-jump-

full&object_id=ii383i&local_base=GENoi-MCGo2 [accessed on

24 Oct. 2017]), paragraph 70.

28 F. Büttner, ‘“Argumentatio” in Bildern der Reformationszeit.

Ein Beitrag zur Bestimmung argumentativer Strukturen in der

Bildkunst’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 57, 1994, no. 1, pp. 24-

25; A. Arnulf, ‘Die Luther-Memoria’, pp. 102-106 (as in note 12).

An interesting instance of such a contemporisation, used in or-

der to defeat Luther and his teachings, is a painting by Barthel

Bruyn the Elder, The Temptation of Christ, in which the Satan has

the facial features of the Reformer of Wittenberg and is wearing

his characteristic gown. See C. Hecht, ‘Gegen die Reformation -

katholische Kunststiftungen in den ersten Jahrzehnten, in Kunst

und Konfession. Katholische Auftragswerke im Zeitalter der Glau-

bensspaltung 1517-1563, ed. by A. Tacke, Regensburg, 2008, pp. 87-

-88, Fig. 7.

29 R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, p. 55 (as in note 3);

H. Schilling, Martin Luther, pp. 507-508 (as in note 2).

30 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 410-411 (as in note 9).

31 Ibidem, pp. 415-417.

32 Ibidem, p. 415. See also R. W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’,

PP- 57-58 (as in note 3).