133

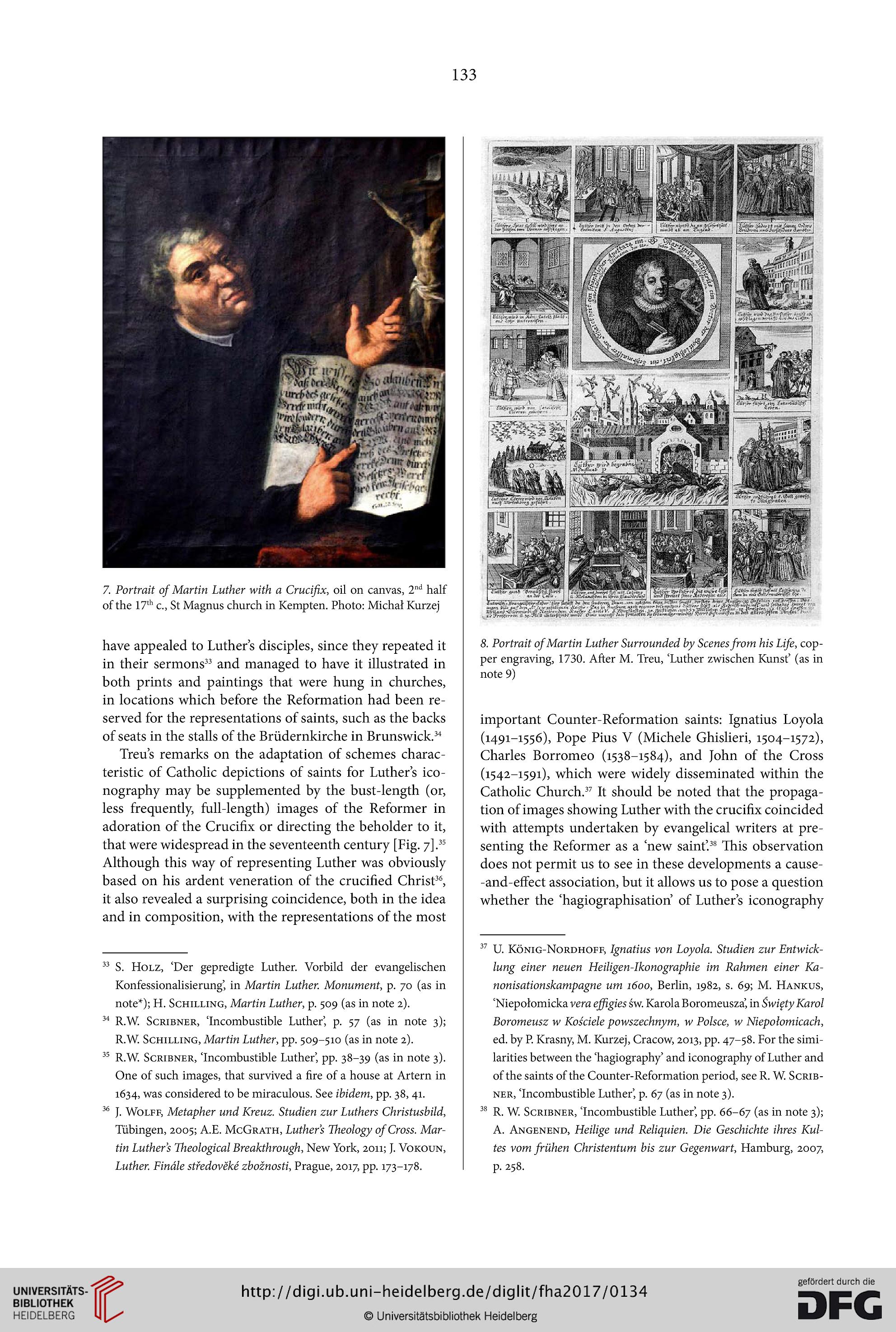

7. Portrait of Martin Luther with a Crucifix, oil on canvas, 2nd half

of the 17th c., St Magnus church in Kempten. Photo: Michał Kurzej

have appealed to Luthers disciples, since they repeated it

in their sermons33 and managed to have it illustrated in

both prints and paintings that were hung in churches,

in locations which before the Reformation had been re-

served for the representations of saints, such as the backs

of seats in the stalls of the Briidernkirche in Brunswick.34

Treus remarks on the adaptation of schemes charac-

teristic of Catholic depictions of saints for Luthers ico-

nography may be supplemented by the bust-length (or,

less frequently, full-length) images of the Reformer in

adoration of the Crucifix or directing the beholder to it,

that were widespread in the seventeenth century [Fig. 7].35

Although this way of representing Luther was obviously

based on his ardent veneration of the crucified Christ36,

it also revealed a surprising coincidence, both in the idea

and in composition, with the representations of the most

33 S. Holz, ‘Der gepredigte Luther. Vorbild der evangelischen

Konfessionalisierung’, in Martin Luther. Monument, p. 70 (as in

note*); H. Schilling, Martin Luther, p. 509 (as in note 2).

34 R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, p. 57 (as in note 3);

R.W. Schilling, Martin Luther, pp. 509-510 (as in note 2).

35 R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, pp. 38-39 (as in note 3).

One of such images, that survived a fire of a house at Artern in

1634, was considered to be miraculous. See ibidem, pp. 38, 41.

36 J. Wolff, Metapher und Kreuz. Studien zur Luthers Christusbild,

Tübingen, 2005; A.E. McGrath, Luthers Theology of Cross. Mar-

tin Luthers Theological Breakthrough, New York, 2011; J. Vokoun,

Luther. Finale stredovëké zboźnosti, Prague, 2017, pp. 173-178.

8. Portrait of Martin Luther Surrounded by Scenes from his Life, cop-

per engraving, 1730. After M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as in

note 9)

important Counter-Reformation saints: Ignatius Loyola

(1491-1556), Pope Pius V (Michele Ghislieri, 1504-1572),

Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), and John of the Cross

(1542-1591), which were widely disseminated within the

Catholic Church.37 It should be noted that the propaga-

tion of images showing Luther with the crucifix coincided

with attempts undertaken by evangelical writers at pre-

senting the Reformer as a new saint’.38 This observation

does not permit us to see in these developments a cause-

-and-effect association, but it allows us to pose a question

whether the ‘hagiographisation of Luthers iconography

37 U. König-Nordhoff, Ignatius von Loyola. Studien zur Entwick-

lung einer neuen Heiligen-Ikonographie im Rahmen einer Ka-

nonisationskampagne um 1600, Berlin, 1982, s. 69; M. Hankus,

‘Niepolomicka vera effigies św. Karola Boromeusza’, in Święty Karol

Boromeusz w Kościele powszechnym, w Polsce, w Niepołomicach,

ed. by P. Krasny, M. Kurzej, Cracow, 2013, pp. 47-58. For the simi-

larities between the ‘hagiography’ and iconography of Luther and

of the saints of the Counter-Reformation period, see R. W. Scrib-

ner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, p. 67 (as in note 3).

38 R. W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, pp. 66-67 (as in note 3);

A. Angenend, Heilige und Reliquien. Die Geschichte ihres Kul-

tes vom frühen Christentum bis zur Gegenwart, Hamburg, 2007,

p. 258.

7. Portrait of Martin Luther with a Crucifix, oil on canvas, 2nd half

of the 17th c., St Magnus church in Kempten. Photo: Michał Kurzej

have appealed to Luthers disciples, since they repeated it

in their sermons33 and managed to have it illustrated in

both prints and paintings that were hung in churches,

in locations which before the Reformation had been re-

served for the representations of saints, such as the backs

of seats in the stalls of the Briidernkirche in Brunswick.34

Treus remarks on the adaptation of schemes charac-

teristic of Catholic depictions of saints for Luthers ico-

nography may be supplemented by the bust-length (or,

less frequently, full-length) images of the Reformer in

adoration of the Crucifix or directing the beholder to it,

that were widespread in the seventeenth century [Fig. 7].35

Although this way of representing Luther was obviously

based on his ardent veneration of the crucified Christ36,

it also revealed a surprising coincidence, both in the idea

and in composition, with the representations of the most

33 S. Holz, ‘Der gepredigte Luther. Vorbild der evangelischen

Konfessionalisierung’, in Martin Luther. Monument, p. 70 (as in

note*); H. Schilling, Martin Luther, p. 509 (as in note 2).

34 R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, p. 57 (as in note 3);

R.W. Schilling, Martin Luther, pp. 509-510 (as in note 2).

35 R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, pp. 38-39 (as in note 3).

One of such images, that survived a fire of a house at Artern in

1634, was considered to be miraculous. See ibidem, pp. 38, 41.

36 J. Wolff, Metapher und Kreuz. Studien zur Luthers Christusbild,

Tübingen, 2005; A.E. McGrath, Luthers Theology of Cross. Mar-

tin Luthers Theological Breakthrough, New York, 2011; J. Vokoun,

Luther. Finale stredovëké zboźnosti, Prague, 2017, pp. 173-178.

8. Portrait of Martin Luther Surrounded by Scenes from his Life, cop-

per engraving, 1730. After M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as in

note 9)

important Counter-Reformation saints: Ignatius Loyola

(1491-1556), Pope Pius V (Michele Ghislieri, 1504-1572),

Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), and John of the Cross

(1542-1591), which were widely disseminated within the

Catholic Church.37 It should be noted that the propaga-

tion of images showing Luther with the crucifix coincided

with attempts undertaken by evangelical writers at pre-

senting the Reformer as a new saint’.38 This observation

does not permit us to see in these developments a cause-

-and-effect association, but it allows us to pose a question

whether the ‘hagiographisation of Luthers iconography

37 U. König-Nordhoff, Ignatius von Loyola. Studien zur Entwick-

lung einer neuen Heiligen-Ikonographie im Rahmen einer Ka-

nonisationskampagne um 1600, Berlin, 1982, s. 69; M. Hankus,

‘Niepolomicka vera effigies św. Karola Boromeusza’, in Święty Karol

Boromeusz w Kościele powszechnym, w Polsce, w Niepołomicach,

ed. by P. Krasny, M. Kurzej, Cracow, 2013, pp. 47-58. For the simi-

larities between the ‘hagiography’ and iconography of Luther and

of the saints of the Counter-Reformation period, see R. W. Scrib-

ner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, p. 67 (as in note 3).

38 R. W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’, pp. 66-67 (as in note 3);

A. Angenend, Heilige und Reliquien. Die Geschichte ihres Kul-

tes vom frühen Christentum bis zur Gegenwart, Hamburg, 2007,

p. 258.