134

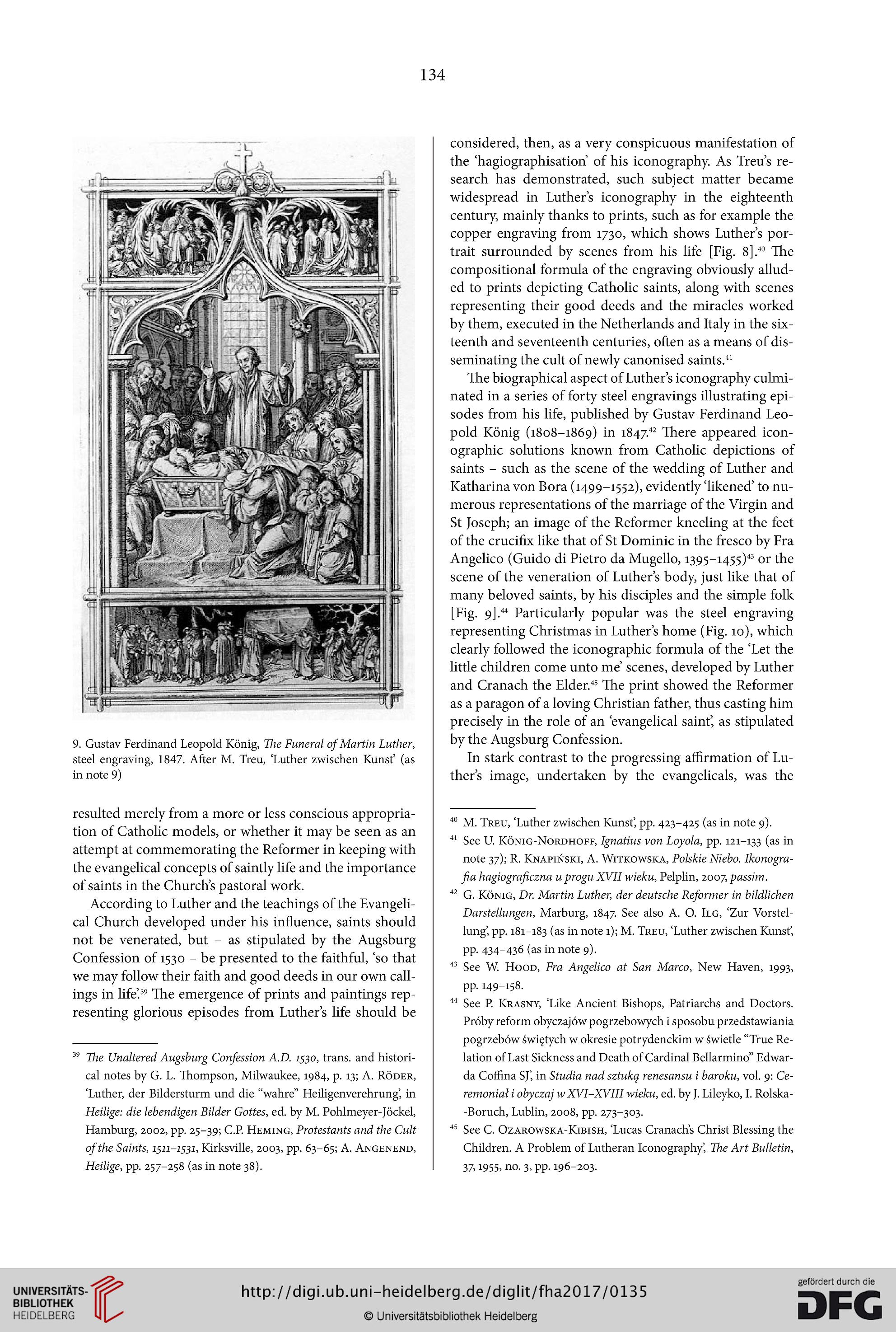

9. Gustav Ferdinand Leopold König, The Funeral of Martin Luther,

steel engraving, 1847. After M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as

in note 9)

resulted merely from a more or less conscious appropria-

tion of Catholic models, or whether it may be seen as an

attempt at commemorating the Reformer in keeping with

the evangelical concepts of saintly life and the importance

of saints in the Church’s pastoral work.

According to Luther and the teachings of the Evangeli-

cal Church developed under his influence, saints should

not be venerated, but - as stipulated by the Augsburg

Confession of 1530 - be presented to the faithful, so that

we may follow their faith and good deeds in our own call-

ings in life’.39 The emergence of prints and paintings rep-

resenting glorious episodes from Luther’s life should be

39 The Unaltered Augsburg Confession A.D. 1530, trans, and histori-

cal notes by G. L. Thompson, Milwaukee, 1984, p. 13; A. Röder,

‘Luther, der Bildersturm und die “wahre” Heiligenverehrung’, in

Heilige: die lebendigen Bilder Gottes, ed. by M. Pohlmeyer-Jockei,

Hamburg, 2002, pp. 25-39; C.P. Heming, Protestants and the Cult

of the Saints, 1511-1531, Kirksville, 2003, pp. 63-65; A. Angenend,

Heilige, pp. 257-258 (as in note 38).

considered, then, as a very conspicuous manifestation of

the ‘hagiographisation of his iconography. As Treu’s re-

search has demonstrated, such subject matter became

widespread in Luther’s iconography in the eighteenth

century, mainly thanks to prints, such as for example the

copper engraving from 1730, which shows Luther’s por-

trait surrounded by scenes from his life [Fig. 8].40 The

compositional formula of the engraving obviously allud-

ed to prints depicting Catholic saints, along with scenes

representing their good deeds and the miracles worked

by them, executed in the Netherlands and Italy in the six-

teenth and seventeenth centuries, often as a means of dis-

seminating the cult of newly canonised saints.41

The biographical aspect of Luther’s iconography culmi-

nated in a series of forty steel engravings illustrating epi-

sodes from his life, published by Gustav Ferdinand Leo-

pold König (1808-1869) in 1847.42 There appeared icon-

ographie solutions known from Catholic depictions of

saints - such as the scene of the wedding of Luther and

Katharina von Bora (1499-1552), evidently ‘likened’ to nu-

merous representations of the marriage of the Virgin and

St Joseph; an image of the Reformer kneeling at the feet

of the crucifix like that of St Dominic in the fresco by Fra

Angelico (Guido di Pietro da Mugello, 1395-1455)43 or the

scene of the veneration of Luther’s body, just like that of

many beloved saints, by his disciples and the simple folk

[Fig. 9].44 Particularly popular was the steel engraving

representing Christmas in Luther’s home (Fig. 10), which

clearly followed the iconographie formula of the ‘Let the

little children come unto me’ scenes, developed by Luther

and Cranach the Elder.45 The print showed the Reformer

as a paragon of a loving Christian father, thus casting him

precisely in the role of an ‘evangelical saint’, as stipulated

by the Augsburg Confession.

In stark contrast to the progressing affirmation of Lu-

ther’s image, undertaken by the evangelicals, was the

40 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 423-425 (as in note 9).

41 See U. König-Nordhoff, Ignatius von Loyola, pp. 121-133 (as in

note 37); R. Knapiński, A. Witkowska, Polskie Niebo. Ikonogra-

fia hagiograficzna u progu XVII wieku, Pelplin, 2007, passim.

42 G. König, Dr. Martin Luther, der deutsche Reformer in bildlichen

Darstellungen, Marburg, 1847. See also A. O. Ilg, ‘Zur Vorstel-

lung’, pp. 181-183 (as in note 1); M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’,

PP- 434-436 (as in note 9).

43 See W. Hood, Fra Angelico at San Marco, New Haven, 1993,

pp. 149-158.

44 See P. Krasny, ‘Like Ancient Bishops, Patriarchs and Doctors.

Próby reform obyczajów pogrzebowych i sposobu przedstawiania

pogrzebów świętych w okresie potrydenckim w świetle “True Re-

lation of Last Sickness and Death of Cardinal Bellarmino” Edwar-

da Cofhna SJ’, in Studia nad sztukę renesansu i baroku, vol. 9: Ce-

remoniał i obyczaj w XVI-XVIII wieku, ed. by J. Lileyko, I. Rolska -

-Boruch, Lublin, 2008, pp. 273-303.

45 See C. Ozarowska-Kibish, ‘Lucas Cranach’s Christ Blessing the

Children. A Problem of Lutheran Iconography’, The Art Bulletin,

37,1955, no. 3, pp. 196-203.

9. Gustav Ferdinand Leopold König, The Funeral of Martin Luther,

steel engraving, 1847. After M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’ (as

in note 9)

resulted merely from a more or less conscious appropria-

tion of Catholic models, or whether it may be seen as an

attempt at commemorating the Reformer in keeping with

the evangelical concepts of saintly life and the importance

of saints in the Church’s pastoral work.

According to Luther and the teachings of the Evangeli-

cal Church developed under his influence, saints should

not be venerated, but - as stipulated by the Augsburg

Confession of 1530 - be presented to the faithful, so that

we may follow their faith and good deeds in our own call-

ings in life’.39 The emergence of prints and paintings rep-

resenting glorious episodes from Luther’s life should be

39 The Unaltered Augsburg Confession A.D. 1530, trans, and histori-

cal notes by G. L. Thompson, Milwaukee, 1984, p. 13; A. Röder,

‘Luther, der Bildersturm und die “wahre” Heiligenverehrung’, in

Heilige: die lebendigen Bilder Gottes, ed. by M. Pohlmeyer-Jockei,

Hamburg, 2002, pp. 25-39; C.P. Heming, Protestants and the Cult

of the Saints, 1511-1531, Kirksville, 2003, pp. 63-65; A. Angenend,

Heilige, pp. 257-258 (as in note 38).

considered, then, as a very conspicuous manifestation of

the ‘hagiographisation of his iconography. As Treu’s re-

search has demonstrated, such subject matter became

widespread in Luther’s iconography in the eighteenth

century, mainly thanks to prints, such as for example the

copper engraving from 1730, which shows Luther’s por-

trait surrounded by scenes from his life [Fig. 8].40 The

compositional formula of the engraving obviously allud-

ed to prints depicting Catholic saints, along with scenes

representing their good deeds and the miracles worked

by them, executed in the Netherlands and Italy in the six-

teenth and seventeenth centuries, often as a means of dis-

seminating the cult of newly canonised saints.41

The biographical aspect of Luther’s iconography culmi-

nated in a series of forty steel engravings illustrating epi-

sodes from his life, published by Gustav Ferdinand Leo-

pold König (1808-1869) in 1847.42 There appeared icon-

ographie solutions known from Catholic depictions of

saints - such as the scene of the wedding of Luther and

Katharina von Bora (1499-1552), evidently ‘likened’ to nu-

merous representations of the marriage of the Virgin and

St Joseph; an image of the Reformer kneeling at the feet

of the crucifix like that of St Dominic in the fresco by Fra

Angelico (Guido di Pietro da Mugello, 1395-1455)43 or the

scene of the veneration of Luther’s body, just like that of

many beloved saints, by his disciples and the simple folk

[Fig. 9].44 Particularly popular was the steel engraving

representing Christmas in Luther’s home (Fig. 10), which

clearly followed the iconographie formula of the ‘Let the

little children come unto me’ scenes, developed by Luther

and Cranach the Elder.45 The print showed the Reformer

as a paragon of a loving Christian father, thus casting him

precisely in the role of an ‘evangelical saint’, as stipulated

by the Augsburg Confession.

In stark contrast to the progressing affirmation of Lu-

ther’s image, undertaken by the evangelicals, was the

40 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 423-425 (as in note 9).

41 See U. König-Nordhoff, Ignatius von Loyola, pp. 121-133 (as in

note 37); R. Knapiński, A. Witkowska, Polskie Niebo. Ikonogra-

fia hagiograficzna u progu XVII wieku, Pelplin, 2007, passim.

42 G. König, Dr. Martin Luther, der deutsche Reformer in bildlichen

Darstellungen, Marburg, 1847. See also A. O. Ilg, ‘Zur Vorstel-

lung’, pp. 181-183 (as in note 1); M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’,

PP- 434-436 (as in note 9).

43 See W. Hood, Fra Angelico at San Marco, New Haven, 1993,

pp. 149-158.

44 See P. Krasny, ‘Like Ancient Bishops, Patriarchs and Doctors.

Próby reform obyczajów pogrzebowych i sposobu przedstawiania

pogrzebów świętych w okresie potrydenckim w świetle “True Re-

lation of Last Sickness and Death of Cardinal Bellarmino” Edwar-

da Cofhna SJ’, in Studia nad sztukę renesansu i baroku, vol. 9: Ce-

remoniał i obyczaj w XVI-XVIII wieku, ed. by J. Lileyko, I. Rolska -

-Boruch, Lublin, 2008, pp. 273-303.

45 See C. Ozarowska-Kibish, ‘Lucas Cranach’s Christ Blessing the

Children. A Problem of Lutheran Iconography’, The Art Bulletin,

37,1955, no. 3, pp. 196-203.