137

ySdjftaiifF b«a4ïwftli?«ne tbitr

l£?n welft bcFltyScmitfïtcbîsjf<t»ct

ïxr lisiiffriit mittifbiirdj &k|clja|f

tfmrotrcbńt/borUwfftyiniMcb

Larm be (îecFrbnü wilffce »ctmr

2tcjmt>umcbaübim3tgriincbUmr

t7tttttc«äcby»f£WF/'«ufftni{bt|éi4

Поп bób« beriłd) bangt am «niij

Coribt Mfen wolfffarnwgaMjt lau ff« r»

3fi Wie TPtmrcrn bcrfcbafft FauftVn

b«t fcWffiin bat№ vylgtfetflo»

(Ю it öatbw« «tm/wtnymaewfltn

fcUbittrofanjńwótfftn rco:Sm

Vitgemjjc nit.fe<te l'tc fdttb<fcbo:fn

yrbWR/bic (itfoltm weybcn

CaiifFniińtfbtytaiiffbicyfrebTbin

Hefurt/tvv.ùvgFrbiircbfdlftbcUr«

î>a* mit «Kin Ь<из kiümmtKfcrt

0о «bfibcbmjMffmfdjabcn

îDomtobi<<Ibii|Toib(yti|lbdab(R

Łmrcbl4f<l>o(f .(JiibjlvnbCarbiniU

ì)ouon Tohßfagtlbjifbwl

ПстотЬ id)y»«bi3/lnr«nnb fcfctób

0olw rt«bFe jlin monet lob.

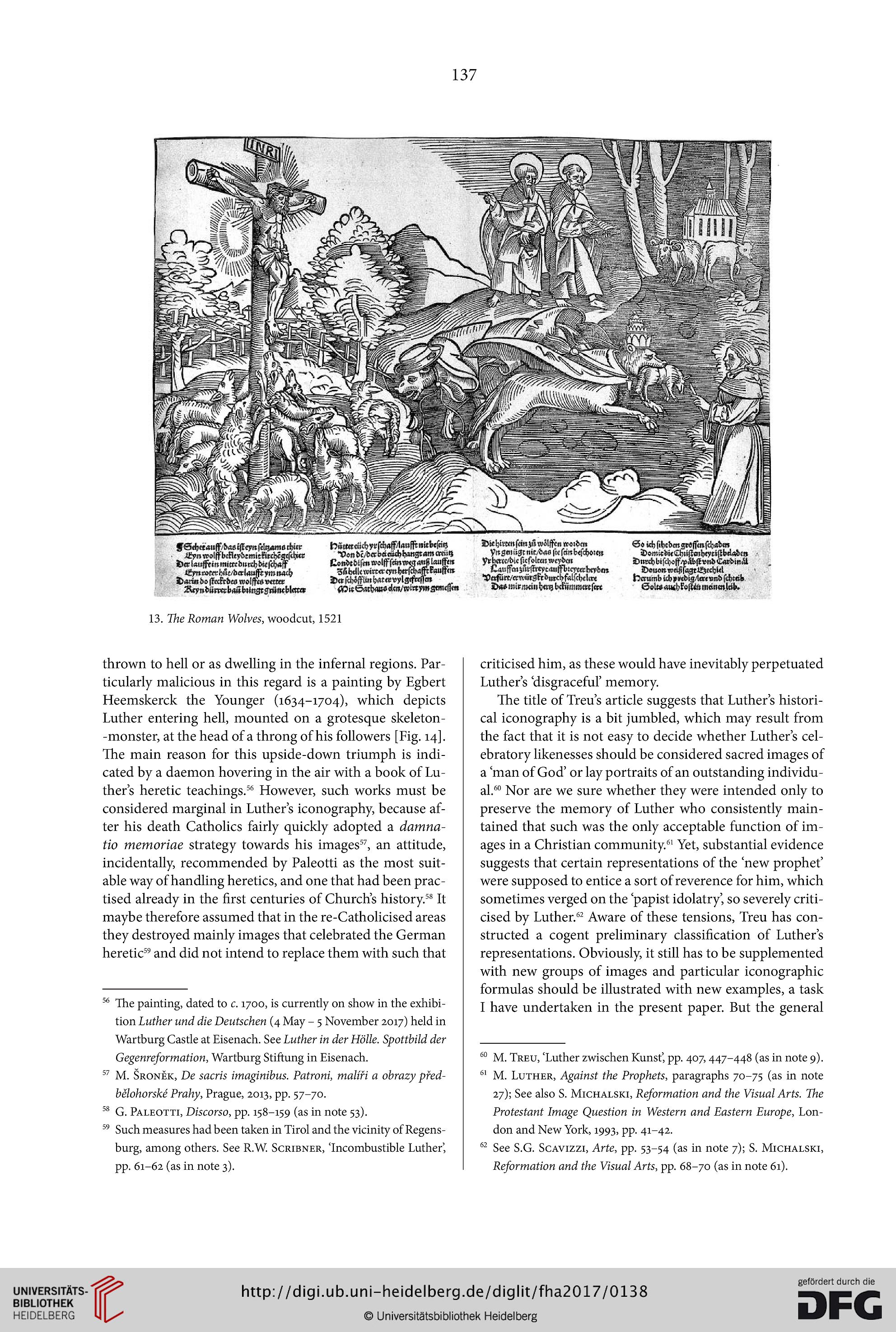

13. The Roman Wolves, woodcut, 1521

thrown to hell or as dwelling in the infernal regions. Par-

ticularly malicious in this regard is a painting by Egbert

Heemskerck the Younger (1634-1704), which depicts

Luther entering hell, mounted on a grotesque skeleton-

-monster, at the head of a throng of his followers [Fig. 14].

The main reason for this upside-down triumph is indi-

cated by a daemon hovering in the air with a book of Lu-

ther’s heretic teachings.56 However, such works must be

considered marginal in Luthers iconography, because af-

ter his death Catholics fairly quickly adopted a damna-

tio memoriae strategy towards his images57, an attitude,

incidentally, recommended by Paleotti as the most suit-

able way of handling heretics, and one that had been prac-

tised already in the first centuries of Church’s history.58 It

maybe therefore assumed that in the re-Catholicised areas

they destroyed mainly images that celebrated the German

heretic59 and did not intend to replace them with such that

56 The painting, dated to c. 1700, is currently on show in the exhibi-

tion Luther und. die Deutschen (4 May - 5 November 2017) held in

Wartburg Castle at Eisenach. See Luther in der Hölle. Spottbild der

Gegenreformation, Wartburg Stiftung in Eisenach.

57 M. Sronèk, De sacris imaginibus. Patroni, malm a obrazy pfed-

bëlohorské Prahy, Prague, 2013, pp. 57-70.

58 G. Paleotti, Discorso, pp. 158-159 (as in note 53).

59 Such measures had been taken in Tirol and the vicinity of Regens-

burg, among others. See R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’,

pp. 61-62 (as in note 3).

criticised him, as these would have inevitably perpetuated

Luther’s ‘disgraceful’ memory.

The title of Treu’s article suggests that Luther’s histori-

cal iconography is a bit jumbled, which may result from

the fact that it is not easy to decide whether Luther’s cel-

ebratory likenesses should be considered sacred images of

a ‘man of God’ or lay portraits of an outstanding individu-

al.60 Nor are we sure whether they were intended only to

preserve the memory of Luther who consistently main-

tained that such was the only acceptable function of im-

ages in a Christian community.61 Yet, substantial evidence

suggests that certain representations of the ‘new prophet’

were supposed to entice a sort of reverence for him, which

sometimes verged on the ‘papist idolatry’, so severely criti-

cised by Luther.62 Aware of these tensions, Treu has con-

structed a cogent preliminary classification of Luther’s

representations. Obviously, it still has to be supplemented

with new groups of images and particular iconographie

formulas should be illustrated with new examples, a task

I have undertaken in the present paper. But the general

60 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 407,447-448 (as in note 9).

61 M. Luther, Against the Prophets, paragraphs 70-75 (as in note

27); See also S. Michalski, Reformation and the Visual Arts. The

Protestant Image Question in Western and Eastern Europe, Lon-

don and New York, 1993, pp. 41-42.

62 See S.G. Soavizzi, Arte, pp. 53-54 (as in note 7); S. Michalski,

Reformation and the Visual Arts, pp. 68-70 (as in note 61).

ySdjftaiifF b«a4ïwftli?«ne tbitr

l£?n welft bcFltyScmitfïtcbîsjf<t»ct

ïxr lisiiffriit mittifbiirdj &k|clja|f

tfmrotrcbńt/borUwfftyiniMcb

Larm be (îecFrbnü wilffce »ctmr

2tcjmt>umcbaübim3tgriincbUmr

t7tttttc«äcby»f£WF/'«ufftni{bt|éi4

Поп bób« beriłd) bangt am «niij

Coribt Mfen wolfffarnwgaMjt lau ff« r»

3fi Wie TPtmrcrn bcrfcbafft FauftVn

b«t fcWffiin bat№ vylgtfetflo»

(Ю it öatbw« «tm/wtnymaewfltn

fcUbittrofanjńwótfftn rco:Sm

Vitgemjjc nit.fe<te l'tc fdttb<fcbo:fn

yrbWR/bic (itfoltm weybcn

CaiifFniińtfbtytaiiffbicyfrebTbin

Hefurt/tvv.ùvgFrbiircbfdlftbcUr«

î>a* mit «Kin Ь<из kiümmtKfcrt

0о «bfibcbmjMffmfdjabcn

îDomtobi<<Ibii|Toib(yti|lbdab(R

Łmrcbl4f<l>o(f .(JiibjlvnbCarbiniU

ì)ouon Tohßfagtlbjifbwl

ПстотЬ id)y»«bi3/lnr«nnb fcfctób

0olw rt«bFe jlin monet lob.

13. The Roman Wolves, woodcut, 1521

thrown to hell or as dwelling in the infernal regions. Par-

ticularly malicious in this regard is a painting by Egbert

Heemskerck the Younger (1634-1704), which depicts

Luther entering hell, mounted on a grotesque skeleton-

-monster, at the head of a throng of his followers [Fig. 14].

The main reason for this upside-down triumph is indi-

cated by a daemon hovering in the air with a book of Lu-

ther’s heretic teachings.56 However, such works must be

considered marginal in Luthers iconography, because af-

ter his death Catholics fairly quickly adopted a damna-

tio memoriae strategy towards his images57, an attitude,

incidentally, recommended by Paleotti as the most suit-

able way of handling heretics, and one that had been prac-

tised already in the first centuries of Church’s history.58 It

maybe therefore assumed that in the re-Catholicised areas

they destroyed mainly images that celebrated the German

heretic59 and did not intend to replace them with such that

56 The painting, dated to c. 1700, is currently on show in the exhibi-

tion Luther und. die Deutschen (4 May - 5 November 2017) held in

Wartburg Castle at Eisenach. See Luther in der Hölle. Spottbild der

Gegenreformation, Wartburg Stiftung in Eisenach.

57 M. Sronèk, De sacris imaginibus. Patroni, malm a obrazy pfed-

bëlohorské Prahy, Prague, 2013, pp. 57-70.

58 G. Paleotti, Discorso, pp. 158-159 (as in note 53).

59 Such measures had been taken in Tirol and the vicinity of Regens-

burg, among others. See R.W. Scribner, ‘Incombustible Luther’,

pp. 61-62 (as in note 3).

criticised him, as these would have inevitably perpetuated

Luther’s ‘disgraceful’ memory.

The title of Treu’s article suggests that Luther’s histori-

cal iconography is a bit jumbled, which may result from

the fact that it is not easy to decide whether Luther’s cel-

ebratory likenesses should be considered sacred images of

a ‘man of God’ or lay portraits of an outstanding individu-

al.60 Nor are we sure whether they were intended only to

preserve the memory of Luther who consistently main-

tained that such was the only acceptable function of im-

ages in a Christian community.61 Yet, substantial evidence

suggests that certain representations of the ‘new prophet’

were supposed to entice a sort of reverence for him, which

sometimes verged on the ‘papist idolatry’, so severely criti-

cised by Luther.62 Aware of these tensions, Treu has con-

structed a cogent preliminary classification of Luther’s

representations. Obviously, it still has to be supplemented

with new groups of images and particular iconographie

formulas should be illustrated with new examples, a task

I have undertaken in the present paper. But the general

60 M. Treu, ‘Luther zwischen Kunst’, pp. 407,447-448 (as in note 9).

61 M. Luther, Against the Prophets, paragraphs 70-75 (as in note

27); See also S. Michalski, Reformation and the Visual Arts. The

Protestant Image Question in Western and Eastern Europe, Lon-

don and New York, 1993, pp. 41-42.

62 See S.G. Soavizzi, Arte, pp. 53-54 (as in note 7); S. Michalski,

Reformation and the Visual Arts, pp. 68-70 (as in note 61).