9

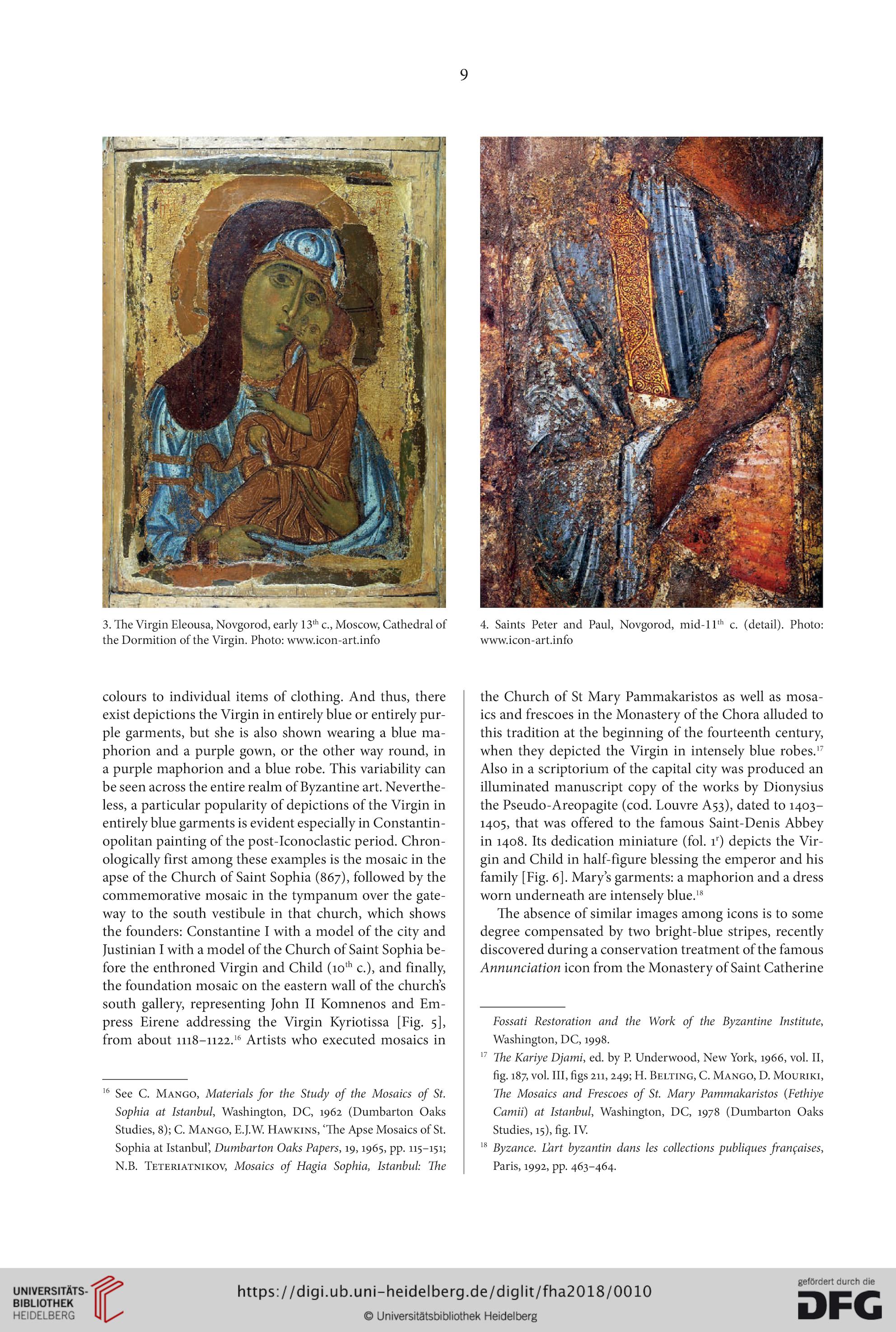

3. The Virgin Eleousa, Novgorod, early 13th c., Moscow, Cathedral of

the Dormition of the Virgin. Photo: www.icon-art.info

colours to individual items of clothing. And thus, there

exist depictions the Virgin in entirely blue or entirely pur-

ple garments, but she is also shown wearing a blue ma-

phorion and a purple gown, or the other way round, in

a purple maphorion and a blue robe. This variability can

be seen across the entire realm of Byzantine art. Neverthe-

less, a particular popularity of depictions of the Virgin in

entirely blue garments is evident especially in Constantin -

opolitan painting of the post-iconoclastic period. Chron-

ologically first among these examples is the mosaic in the

apse of the Church of Saint Sophia (867), followed by the

commemorative mosaic in the tympanum over the gate-

way to the south vestibule in that church, which shows

the founders: Constantine I with a model of the city and

Justinian I with a model of the Church of Saint Sophia be-

fore the enthroned Virgin and Child (10th c.), and finally,

the foundation mosaic on the eastern wall of the church’s

south gallery, representing John II Komnenos and Em-

press Eirene addressing the Virgin Kyriotissa [Fig. 5],

from about 1118-1122.16 * 16 Artists who executed mosaics in

16 See C. Mango, Materials for the Study of the Mosaics of St.

Sophia at Istanbul, Washington, DC, 1962 (Dumbarton Oaks

Studies, 8); C. Mango, E.J.W. Hawkins, ‘The Apse Mosaics of St.

Sophia at Istanbul’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 19,1965, pp. 115-151;

N.B. Teteriatnikov, Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The

4. Saints Peter and Paul, Novgorod, mid-11th c. (detail). Photo:

www.icon-art.info

the Church of St Mary Pammakaristos as well as mosa-

ics and frescoes in the Monastery of the Chora alluded to

this tradition at the beginning of the fourteenth century,

when they depicted the Virgin in intensely blue robes.17

Also in a scriptorium of the capital city was produced an

illuminated manuscript copy of the works by Dionysius

the Pseudo-Areopagite (cod. Louvre A53), dated to 1403-

1405, that was offered to the famous Saint-Denis Abbey

in 1408. Its dedication miniature (fol. ir) depicts the Vir-

gin and Child in half-figure blessing the emperor and his

family [Fig. 6]. Marys garments: a maphorion and a dress

worn underneath are intensely blue.18

The absence of similar images among icons is to some

degree compensated by two bright-blue stripes, recently

discovered during a conservation treatment of the famous

Annunciation icon from the Monastery of Saint Catherine

Fossati Restoration and the Work of the Byzantine Institute,

Washington, DC, 1998.

17 The Kariye Djami, ed. by P. Underwood, New York, 1966, vol. II,

fig. 187, vol. Ill, figs 211,249; H. Belting, C. Mango, D. Mouriki,

The Mosaics and Frescoes of St. Mary Pammakaristos (Fethiye

Camo) at Istanbul, Washington, DC, 1978 (Dumbarton Oaks

Studies, 15), fig. IV.

18 Byzance. L’art byzantin dans les collections publiques françaises,

Paris, 1992, pp. 463-464.

3. The Virgin Eleousa, Novgorod, early 13th c., Moscow, Cathedral of

the Dormition of the Virgin. Photo: www.icon-art.info

colours to individual items of clothing. And thus, there

exist depictions the Virgin in entirely blue or entirely pur-

ple garments, but she is also shown wearing a blue ma-

phorion and a purple gown, or the other way round, in

a purple maphorion and a blue robe. This variability can

be seen across the entire realm of Byzantine art. Neverthe-

less, a particular popularity of depictions of the Virgin in

entirely blue garments is evident especially in Constantin -

opolitan painting of the post-iconoclastic period. Chron-

ologically first among these examples is the mosaic in the

apse of the Church of Saint Sophia (867), followed by the

commemorative mosaic in the tympanum over the gate-

way to the south vestibule in that church, which shows

the founders: Constantine I with a model of the city and

Justinian I with a model of the Church of Saint Sophia be-

fore the enthroned Virgin and Child (10th c.), and finally,

the foundation mosaic on the eastern wall of the church’s

south gallery, representing John II Komnenos and Em-

press Eirene addressing the Virgin Kyriotissa [Fig. 5],

from about 1118-1122.16 * 16 Artists who executed mosaics in

16 See C. Mango, Materials for the Study of the Mosaics of St.

Sophia at Istanbul, Washington, DC, 1962 (Dumbarton Oaks

Studies, 8); C. Mango, E.J.W. Hawkins, ‘The Apse Mosaics of St.

Sophia at Istanbul’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 19,1965, pp. 115-151;

N.B. Teteriatnikov, Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The

4. Saints Peter and Paul, Novgorod, mid-11th c. (detail). Photo:

www.icon-art.info

the Church of St Mary Pammakaristos as well as mosa-

ics and frescoes in the Monastery of the Chora alluded to

this tradition at the beginning of the fourteenth century,

when they depicted the Virgin in intensely blue robes.17

Also in a scriptorium of the capital city was produced an

illuminated manuscript copy of the works by Dionysius

the Pseudo-Areopagite (cod. Louvre A53), dated to 1403-

1405, that was offered to the famous Saint-Denis Abbey

in 1408. Its dedication miniature (fol. ir) depicts the Vir-

gin and Child in half-figure blessing the emperor and his

family [Fig. 6]. Marys garments: a maphorion and a dress

worn underneath are intensely blue.18

The absence of similar images among icons is to some

degree compensated by two bright-blue stripes, recently

discovered during a conservation treatment of the famous

Annunciation icon from the Monastery of Saint Catherine

Fossati Restoration and the Work of the Byzantine Institute,

Washington, DC, 1998.

17 The Kariye Djami, ed. by P. Underwood, New York, 1966, vol. II,

fig. 187, vol. Ill, figs 211,249; H. Belting, C. Mango, D. Mouriki,

The Mosaics and Frescoes of St. Mary Pammakaristos (Fethiye

Camo) at Istanbul, Washington, DC, 1978 (Dumbarton Oaks

Studies, 15), fig. IV.

18 Byzance. L’art byzantin dans les collections publiques françaises,

Paris, 1992, pp. 463-464.