12

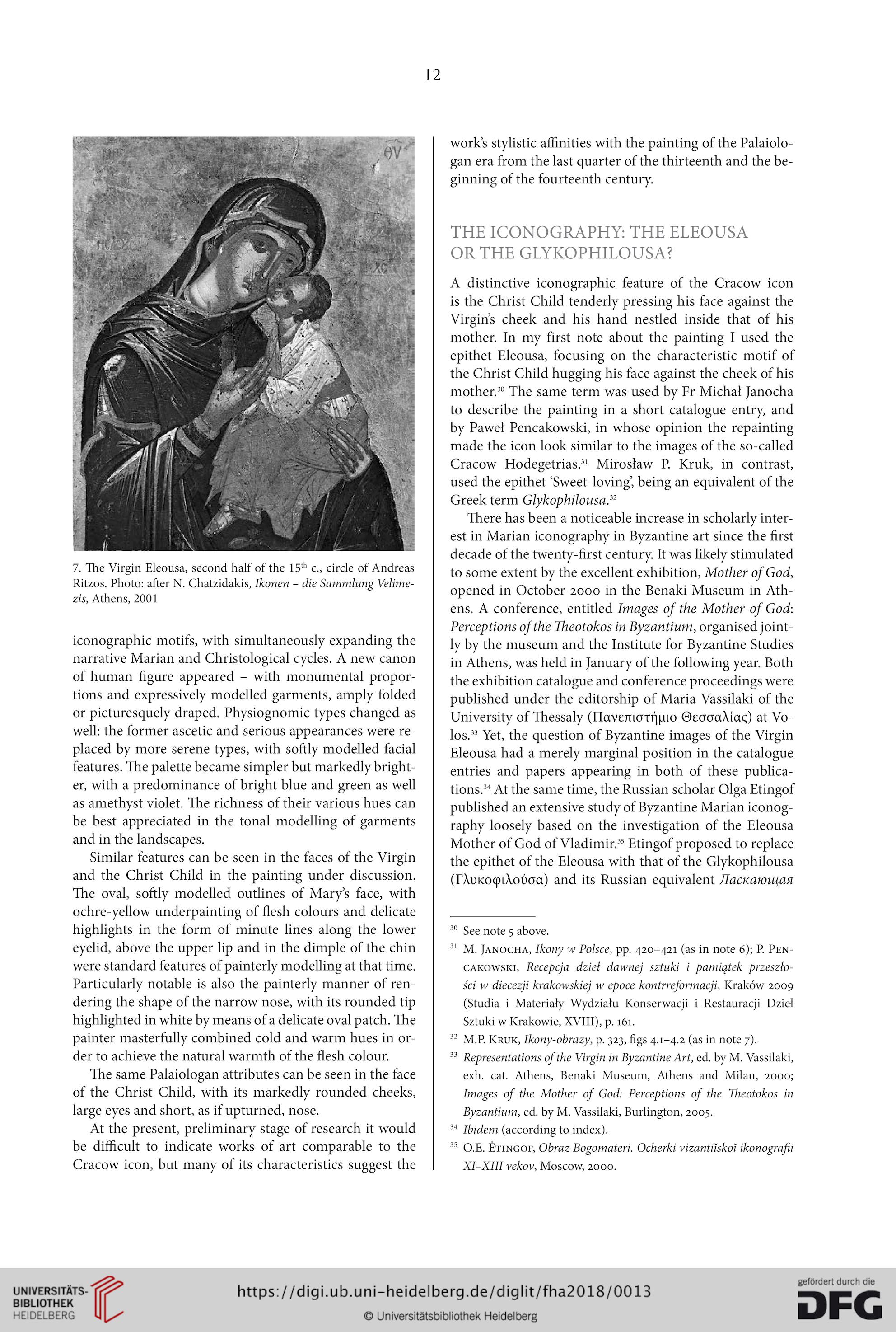

7. The Virgin Eleousa, second half of the 15th c., circle of Andreas

Ritzos. Photo: after N. Chatzidakis, Ikonen - die Sammlung Velime-

zis, Athens, 2001

iconographie motifs, with simultaneously expanding the

narrative Marian and Christological cycles. A new canon

of human figure appeared - with monumental propor-

tions and expressively modelled garments, amply folded

or picturesquely draped. Physiognomic types changed as

well: the former ascetic and serious appearances were re-

placed by more serene types, with softly modelled facial

features. The palette became simpler but markedly bright-

er, with a predominance of bright blue and green as well

as amethyst violet. The richness of their various hues can

be best appreciated in the tonal modelling of garments

and in the landscapes.

Similar features can be seen in the faces of the Virgin

and the Christ Child in the painting under discussion.

The oval, softly modelled outlines of Mary’s face, with

ochre-yellow underpainting of flesh colours and delicate

highlights in the form of minute lines along the lower

eyelid, above the upper lip and in the dimple of the chin

were standard features of painterly modelling at that time.

Particularly notable is also the painterly manner of ren-

dering the shape of the narrow nose, with its rounded tip

highlighted in white by means of a delicate oval patch. The

painter masterfully combined cold and warm hues in or-

der to achieve the natural warmth of the flesh colour.

The same Palaiologan attributes can be seen in the face

of the Christ Child, with its markedly rounded cheeks,

large eyes and short, as if upturned, nose.

At the present, preliminary stage of research it would

be difficult to indicate works of art comparable to the

Cracow icon, but many of its characteristics suggest the

works stylistic affinities with the painting of the Palaiolo-

gan era from the last quarter of the thirteenth and the be-

ginning of the fourteenth century.

THE ICONOGRAPHY: THE ELEOUSA

OR THE GLYKOPHILOUSA?

A distinctive iconographie feature of the Cracow icon

is the Christ Child tenderly pressing his face against the

Virgins cheek and his hand nestled inside that of his

mother. In my first note about the painting I used the

epithet Eleousa, focusing on the characteristic motif of

the Christ Child hugging his face against the cheek of his

mother.30 The same term was used by Fr Michal Janocha

to describe the painting in a short catalogue entry, and

by Paweł Pencakowski, in whose opinion the repainting

made the icon look similar to the images of the so-called

Cracow Hodegetrias.31 Mirosław P. Kruk, in contrast,

used the epithet ‘Sweet-loving’, being an equivalent of the

Greek term Glykophilousa.32

There has been a noticeable increase in scholarly inter-

est in Marian iconography in Byzantine art since the first

decade of the twenty-first century. It was likely stimulated

to some extent by the excellent exhibition, Mother of God,

opened in October 2000 in the Benaki Museum in Ath-

ens. A conference, entitled Images of the Mother of God:

Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, organised joint-

ly by the museum and the Institute for Byzantine Studies

in Athens, was held in January of the following year. Both

the exhibition catalogue and conference proceedings were

published under the editorship of Maria Vassilaki of the

University of Thessaly (IIaveniOTf]pio GeooaXiaç) at Vo-

los.33 Yet, the question of Byzantine images of the Virgin

Eleousa had a merely marginal position in the catalogue

entries and papers appearing in both of these publica-

tions.34 At the same time, the Russian scholar Olga Etingof

published an extensive study of Byzantine Marian iconog-

raphy loosely based on the investigation of the Eleousa

Mother of God of Vladimir.35 Etingof proposed to replace

the epithet of the Eleousa with that of the Glykophilousa

(rXvKocpiXovoa) and its Russian equivalent Ласкающая

30 See note 5 above.

31 M. Janocha, Ikony w Polsce, pp. 420-421 (as in note 6); P. Pen-

cakowski, Recepcja dzieł dawnej sztuki i pamiątek przeszło-

ści w diecezji krakowskiej w epoce kontrreformacji, Kraków 2009

(Studia i Materiały Wydziału Konserwacji i Restauracji Dzieł

Sztuki w Krakowie, XVIII), p. 161.

32 M.P. Kruk, Ikony-obrazy, p. 323, figs 4.1-4.2 (as in note 7).

33 Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art, ed. by M. Vassilaki,

exh. cat. Athens, Benaki Museum, Athens and Milan, 2000;

Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in

Byzantium, ed. by M. Vassilaki, Burlington, 2005.

34 Ibidem (according to index).

35 O.E. Etingof, Obraz Bogomateri. Ocherki vizantiiskoi ikonografii

XI-XIII vekov, Moscow, 2000.

7. The Virgin Eleousa, second half of the 15th c., circle of Andreas

Ritzos. Photo: after N. Chatzidakis, Ikonen - die Sammlung Velime-

zis, Athens, 2001

iconographie motifs, with simultaneously expanding the

narrative Marian and Christological cycles. A new canon

of human figure appeared - with monumental propor-

tions and expressively modelled garments, amply folded

or picturesquely draped. Physiognomic types changed as

well: the former ascetic and serious appearances were re-

placed by more serene types, with softly modelled facial

features. The palette became simpler but markedly bright-

er, with a predominance of bright blue and green as well

as amethyst violet. The richness of their various hues can

be best appreciated in the tonal modelling of garments

and in the landscapes.

Similar features can be seen in the faces of the Virgin

and the Christ Child in the painting under discussion.

The oval, softly modelled outlines of Mary’s face, with

ochre-yellow underpainting of flesh colours and delicate

highlights in the form of minute lines along the lower

eyelid, above the upper lip and in the dimple of the chin

were standard features of painterly modelling at that time.

Particularly notable is also the painterly manner of ren-

dering the shape of the narrow nose, with its rounded tip

highlighted in white by means of a delicate oval patch. The

painter masterfully combined cold and warm hues in or-

der to achieve the natural warmth of the flesh colour.

The same Palaiologan attributes can be seen in the face

of the Christ Child, with its markedly rounded cheeks,

large eyes and short, as if upturned, nose.

At the present, preliminary stage of research it would

be difficult to indicate works of art comparable to the

Cracow icon, but many of its characteristics suggest the

works stylistic affinities with the painting of the Palaiolo-

gan era from the last quarter of the thirteenth and the be-

ginning of the fourteenth century.

THE ICONOGRAPHY: THE ELEOUSA

OR THE GLYKOPHILOUSA?

A distinctive iconographie feature of the Cracow icon

is the Christ Child tenderly pressing his face against the

Virgins cheek and his hand nestled inside that of his

mother. In my first note about the painting I used the

epithet Eleousa, focusing on the characteristic motif of

the Christ Child hugging his face against the cheek of his

mother.30 The same term was used by Fr Michal Janocha

to describe the painting in a short catalogue entry, and

by Paweł Pencakowski, in whose opinion the repainting

made the icon look similar to the images of the so-called

Cracow Hodegetrias.31 Mirosław P. Kruk, in contrast,

used the epithet ‘Sweet-loving’, being an equivalent of the

Greek term Glykophilousa.32

There has been a noticeable increase in scholarly inter-

est in Marian iconography in Byzantine art since the first

decade of the twenty-first century. It was likely stimulated

to some extent by the excellent exhibition, Mother of God,

opened in October 2000 in the Benaki Museum in Ath-

ens. A conference, entitled Images of the Mother of God:

Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, organised joint-

ly by the museum and the Institute for Byzantine Studies

in Athens, was held in January of the following year. Both

the exhibition catalogue and conference proceedings were

published under the editorship of Maria Vassilaki of the

University of Thessaly (IIaveniOTf]pio GeooaXiaç) at Vo-

los.33 Yet, the question of Byzantine images of the Virgin

Eleousa had a merely marginal position in the catalogue

entries and papers appearing in both of these publica-

tions.34 At the same time, the Russian scholar Olga Etingof

published an extensive study of Byzantine Marian iconog-

raphy loosely based on the investigation of the Eleousa

Mother of God of Vladimir.35 Etingof proposed to replace

the epithet of the Eleousa with that of the Glykophilousa

(rXvKocpiXovoa) and its Russian equivalent Ласкающая

30 See note 5 above.

31 M. Janocha, Ikony w Polsce, pp. 420-421 (as in note 6); P. Pen-

cakowski, Recepcja dzieł dawnej sztuki i pamiątek przeszło-

ści w diecezji krakowskiej w epoce kontrreformacji, Kraków 2009

(Studia i Materiały Wydziału Konserwacji i Restauracji Dzieł

Sztuki w Krakowie, XVIII), p. 161.

32 M.P. Kruk, Ikony-obrazy, p. 323, figs 4.1-4.2 (as in note 7).

33 Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art, ed. by M. Vassilaki,

exh. cat. Athens, Benaki Museum, Athens and Milan, 2000;

Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in

Byzantium, ed. by M. Vassilaki, Burlington, 2005.

34 Ibidem (according to index).

35 O.E. Etingof, Obraz Bogomateri. Ocherki vizantiiskoi ikonografii

XI-XIII vekov, Moscow, 2000.