17

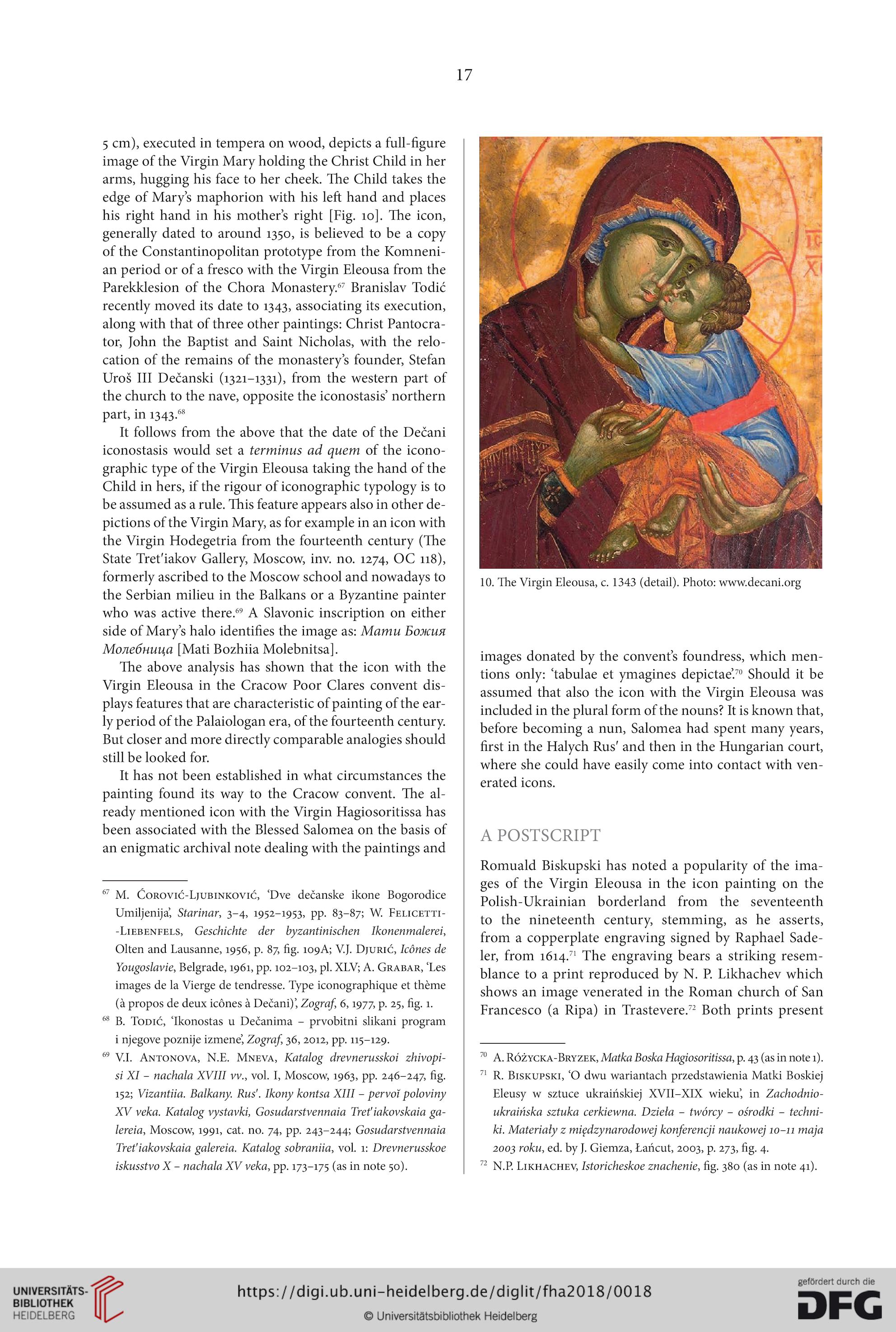

5 cm), executed in tempera on wood, depicts a full-figure

image of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child in her

arms, hugging his face to her cheek. The Child takes the

edge of Marys maphorion with his left hand and places

his right hand in his mothers right [Fig. 10]. The icon,

generally dated to around 1350, is believed to be a copy

of the Constantinopolitan prototype from the Komneni-

an period or of a fresco with the Virgin Eleousa from the

Parekklesion of the Chora Monastery.67 Branislav Todić

recently moved its date to 1343, associating its execution,

along with that of three other paintings: Christ Pantocra-

tor, John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas, with the relo-

cation of the remains of the monastery’s founder, Stefan

Uroś III Dećanski (1321-1331), from the western part of

the church to the nave, opposite the iconostasis’ northern

part, in 1343.68

It follows from the above that the date of the Decani

iconostasis would set a terminus ad quem of the icono-

graphie type of the Virgin Eleousa taking the hand of the

Child in hers, if the rigour of iconographie typology is to

be assumed as a rule. This feature appears also in other de-

pictions of the Virgin Mary, as for example in an icon with

the Virgin Hodegetria from the fourteenth century (The

State Tret'iakov Gallery, Moscow, inv. no. 1274, OC 118),

formerly ascribed to the Moscow school and nowadays to

the Serbian milieu in the Balkans or a Byzantine painter

who was active there.69 A Slavonic inscription on either

side of Mary’s halo identifies the image as: Mamu Божия

Молебница [Mati Bozhiia Molebnitsa].

The above analysis has shown that the icon with the

Virgin Eleousa in the Cracow Poor Clares convent dis-

plays features that are characteristic of painting of the ear-

ly period of the Palaiologan era, of the fourteenth century.

But closer and more directly comparable analogies should

still be looked for.

It has not been established in what circumstances the

painting found its way to the Cracow convent. The al-

ready mentioned icon with the Virgin Hagiosoritissa has

been associated with the Blessed Salomea on the basis of

an enigmatic archival note dealing with the paintings and

67 M. Corovic-Ljubinkovic, ‘Dve dećanske ikone Bogorodice

Umiljenija’, Sfarinar, 3-4, 1952-1953, pp. 83-87; W. Felicetti-

-Liebenfels, Geschichte der byzantinischen Ikonenmalerei,

Olten and Lausanne, 1956, p. 87, fig. 109A; V.J. Djurić, Icônes de

Yougoslavie, Belgrade, 1961, pp. 102-103, pl. XLV; A. Grabar, ‘Les

images de la Vierge de tendresse. Type iconographique et thème

(à propos de deux icônes à Decani)’, Zograf, 6,1977, p. 25, fig. 1.

68 B. Todić, ‘Ikonostas u Dećanima - prvobitni slikani program

i njegove poznije izmene’, Zograf, 36, 2012, pp. 115-129.

69 V.I. Antonova, N.E. Mneva, Katalog drevnerusskoi zhivopi-

si XI - nachala XVIII vv., vol. I, Moscow, 1963, pp. 246-247, fig.

152; Vizantiia. Bałkany. Rus'. Ikony kontsa XIII - pervoï poloviny

XV veka. Katalog vystavki, Gosudarstvennaia Tret'iakovskaia ga-

lereia, Moscow, 1991, cat. no. 74, pp. 243-244; Gosudarstvennaia

Tret'iakovskaia galereia. Katalog sobraniia, vol. 1: Drevnerusskoe

iskusstvo X - nachala XV veka, pp. 173-175 (as in note 50).

10. The Virgin Eleousa, c. 1343 (detail). Photo: www.decani.org

images donated by the convent’s foundress, which men-

tions only: ‘tabulae et ymagines depictae’.70 Should it be

assumed that also the icon with the Virgin Eleousa was

included in the plural form of the nouns? It is known that,

before becoming a nun, Salomea had spent many years,

first in the Halych Rus' and then in the Hungarian court,

where she could have easily come into contact with ven-

erated icons.

A POSTSCRIPT

Romuald Biskupski has noted a popularity of the ima-

ges of the Virgin Eleousa in the icon painting on the

Polish-Ukrainian borderland from the seventeenth

to the nineteenth century, stemming, as he asserts,

from a copperplate engraving signed by Raphael Sade-

ler, from 1614.71 The engraving bears a striking resem-

blance to a print reproduced by N. P. Likhachev which

shows an image venerated in the Roman church of San

Francesco (a Ripa) in Trastevere.72 Both prints present

70 A. Różycka-Bryzek, Matka Boska Hagiosoritissa, p. 43 (as in note 1).

71 R. Biskupski, ‘O dwu wariantach przedstawienia Matki Boskiej

Eleusy w sztuce ukraińskiej XVII-XIX wieku’, in Zachodnio-

ukraińska sztuka cerkiewna. Dzieła - twórcy - ośrodki - techni-

ki. Materiały z międzynarodowej konferencji naukowej 10-11 maja

2003 roku, ed. by ƒ. Giemza, Łańcut, 2003, p. 273, fig. 4.

72 N.P. Likhachev, Istoricheskoe znachenie, fig. 380 (as in note 41).

5 cm), executed in tempera on wood, depicts a full-figure

image of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child in her

arms, hugging his face to her cheek. The Child takes the

edge of Marys maphorion with his left hand and places

his right hand in his mothers right [Fig. 10]. The icon,

generally dated to around 1350, is believed to be a copy

of the Constantinopolitan prototype from the Komneni-

an period or of a fresco with the Virgin Eleousa from the

Parekklesion of the Chora Monastery.67 Branislav Todić

recently moved its date to 1343, associating its execution,

along with that of three other paintings: Christ Pantocra-

tor, John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas, with the relo-

cation of the remains of the monastery’s founder, Stefan

Uroś III Dećanski (1321-1331), from the western part of

the church to the nave, opposite the iconostasis’ northern

part, in 1343.68

It follows from the above that the date of the Decani

iconostasis would set a terminus ad quem of the icono-

graphie type of the Virgin Eleousa taking the hand of the

Child in hers, if the rigour of iconographie typology is to

be assumed as a rule. This feature appears also in other de-

pictions of the Virgin Mary, as for example in an icon with

the Virgin Hodegetria from the fourteenth century (The

State Tret'iakov Gallery, Moscow, inv. no. 1274, OC 118),

formerly ascribed to the Moscow school and nowadays to

the Serbian milieu in the Balkans or a Byzantine painter

who was active there.69 A Slavonic inscription on either

side of Mary’s halo identifies the image as: Mamu Божия

Молебница [Mati Bozhiia Molebnitsa].

The above analysis has shown that the icon with the

Virgin Eleousa in the Cracow Poor Clares convent dis-

plays features that are characteristic of painting of the ear-

ly period of the Palaiologan era, of the fourteenth century.

But closer and more directly comparable analogies should

still be looked for.

It has not been established in what circumstances the

painting found its way to the Cracow convent. The al-

ready mentioned icon with the Virgin Hagiosoritissa has

been associated with the Blessed Salomea on the basis of

an enigmatic archival note dealing with the paintings and

67 M. Corovic-Ljubinkovic, ‘Dve dećanske ikone Bogorodice

Umiljenija’, Sfarinar, 3-4, 1952-1953, pp. 83-87; W. Felicetti-

-Liebenfels, Geschichte der byzantinischen Ikonenmalerei,

Olten and Lausanne, 1956, p. 87, fig. 109A; V.J. Djurić, Icônes de

Yougoslavie, Belgrade, 1961, pp. 102-103, pl. XLV; A. Grabar, ‘Les

images de la Vierge de tendresse. Type iconographique et thème

(à propos de deux icônes à Decani)’, Zograf, 6,1977, p. 25, fig. 1.

68 B. Todić, ‘Ikonostas u Dećanima - prvobitni slikani program

i njegove poznije izmene’, Zograf, 36, 2012, pp. 115-129.

69 V.I. Antonova, N.E. Mneva, Katalog drevnerusskoi zhivopi-

si XI - nachala XVIII vv., vol. I, Moscow, 1963, pp. 246-247, fig.

152; Vizantiia. Bałkany. Rus'. Ikony kontsa XIII - pervoï poloviny

XV veka. Katalog vystavki, Gosudarstvennaia Tret'iakovskaia ga-

lereia, Moscow, 1991, cat. no. 74, pp. 243-244; Gosudarstvennaia

Tret'iakovskaia galereia. Katalog sobraniia, vol. 1: Drevnerusskoe

iskusstvo X - nachala XV veka, pp. 173-175 (as in note 50).

10. The Virgin Eleousa, c. 1343 (detail). Photo: www.decani.org

images donated by the convent’s foundress, which men-

tions only: ‘tabulae et ymagines depictae’.70 Should it be

assumed that also the icon with the Virgin Eleousa was

included in the plural form of the nouns? It is known that,

before becoming a nun, Salomea had spent many years,

first in the Halych Rus' and then in the Hungarian court,

where she could have easily come into contact with ven-

erated icons.

A POSTSCRIPT

Romuald Biskupski has noted a popularity of the ima-

ges of the Virgin Eleousa in the icon painting on the

Polish-Ukrainian borderland from the seventeenth

to the nineteenth century, stemming, as he asserts,

from a copperplate engraving signed by Raphael Sade-

ler, from 1614.71 The engraving bears a striking resem-

blance to a print reproduced by N. P. Likhachev which

shows an image venerated in the Roman church of San

Francesco (a Ripa) in Trastevere.72 Both prints present

70 A. Różycka-Bryzek, Matka Boska Hagiosoritissa, p. 43 (as in note 1).

71 R. Biskupski, ‘O dwu wariantach przedstawienia Matki Boskiej

Eleusy w sztuce ukraińskiej XVII-XIX wieku’, in Zachodnio-

ukraińska sztuka cerkiewna. Dzieła - twórcy - ośrodki - techni-

ki. Materiały z międzynarodowej konferencji naukowej 10-11 maja

2003 roku, ed. by ƒ. Giemza, Łańcut, 2003, p. 273, fig. 4.

72 N.P. Likhachev, Istoricheskoe znachenie, fig. 380 (as in note 41).