143

VI. The Contribution of the Missions to Medical Care

With education, medical care has been, and remains, one of the two important

secular activities of the missions. For the Africans, described by the Kenyan

philosopher and theologian J. S. MBITI (1969, 1) as “notoriously religious”,

religion and medicine are traditionally bound together. Thus it was seen as

quite fitting that the missionaries who brought a new faith were also doctors

who healed the sick.

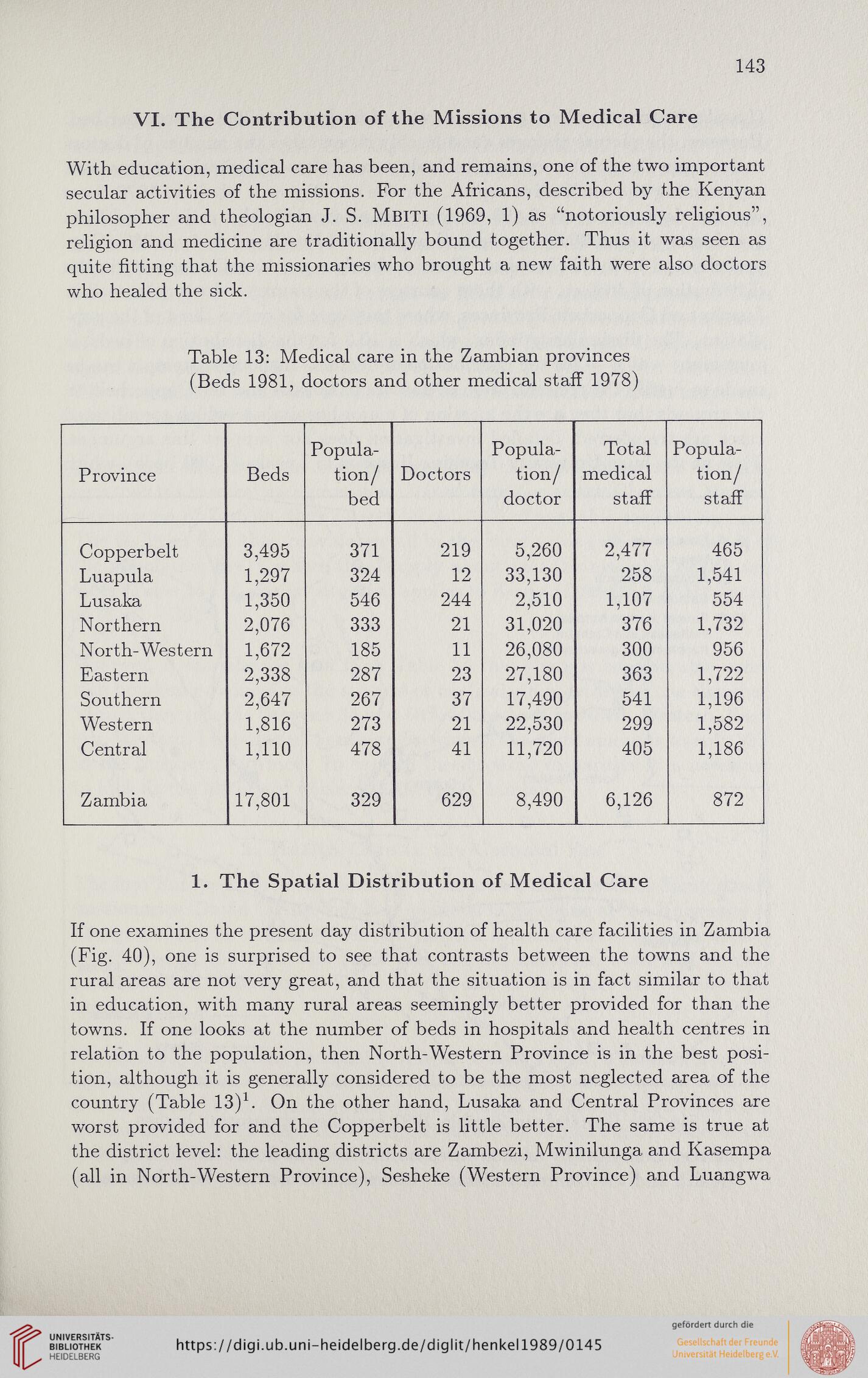

Table 13: Medical care in the Zambian provinces

(Beds 1981, doctors and other medical staff 1978)

Province

Beds

Popula-

tion/

bed

Doctors

Popula-

tion/

doctor

Total

medical

staff

Popula-

tion/

staff

Copperbelt

3,495

371

219

5,260

2,477

465

Luapula

1,297

324

12

33,130

258

1,541

Lusaka

1,350

546

244

2,510

1,107

554

Northern

2,076

333

21

31,020

376

1,732

North-Western

1,672

185

11

26,080

300

956

Eastern

2,338

287

23

27,180

363

1,722

Southern

2,647

267

37

17,490

541

1,196

Western

1,816

273

21

22,530

299

1,582

Central

1,110

478

41

11,720

405

1,186

Zambia

17,801

329

629

8,490

6,126

872

1. The Spatial Distribution of Medical Care

If one examines the present day distribution of health care facilities in Zambia

(Fig. 40), one is surprised to see that contrasts between the towns and the

rural areas are not very great, and that the situation is in fact similar to that

in education, with many rural areas seemingly better provided for than the

towns. If one looks at the number of beds in hospitals and health centres in

relation to the population, then North-Western Province is in the best posi-

tion, although it is generally considered to be the most neglected area of the

country (Table 13)1. On the other hand, Lusaka and Central Provinces are

worst provided for and the Copperbelt is little better. The same is true at

the district level: the leading districts are Zambezi, Mwinilunga and Kasempa

(all in North-Western Province), Sesheke (Western Province) and Luangwa

VI. The Contribution of the Missions to Medical Care

With education, medical care has been, and remains, one of the two important

secular activities of the missions. For the Africans, described by the Kenyan

philosopher and theologian J. S. MBITI (1969, 1) as “notoriously religious”,

religion and medicine are traditionally bound together. Thus it was seen as

quite fitting that the missionaries who brought a new faith were also doctors

who healed the sick.

Table 13: Medical care in the Zambian provinces

(Beds 1981, doctors and other medical staff 1978)

Province

Beds

Popula-

tion/

bed

Doctors

Popula-

tion/

doctor

Total

medical

staff

Popula-

tion/

staff

Copperbelt

3,495

371

219

5,260

2,477

465

Luapula

1,297

324

12

33,130

258

1,541

Lusaka

1,350

546

244

2,510

1,107

554

Northern

2,076

333

21

31,020

376

1,732

North-Western

1,672

185

11

26,080

300

956

Eastern

2,338

287

23

27,180

363

1,722

Southern

2,647

267

37

17,490

541

1,196

Western

1,816

273

21

22,530

299

1,582

Central

1,110

478

41

11,720

405

1,186

Zambia

17,801

329

629

8,490

6,126

872

1. The Spatial Distribution of Medical Care

If one examines the present day distribution of health care facilities in Zambia

(Fig. 40), one is surprised to see that contrasts between the towns and the

rural areas are not very great, and that the situation is in fact similar to that

in education, with many rural areas seemingly better provided for than the

towns. If one looks at the number of beds in hospitals and health centres in

relation to the population, then North-Western Province is in the best posi-

tion, although it is generally considered to be the most neglected area of the

country (Table 13)1. On the other hand, Lusaka and Central Provinces are

worst provided for and the Copperbelt is little better. The same is true at

the district level: the leading districts are Zambezi, Mwinilunga and Kasempa

(all in North-Western Province), Sesheke (Western Province) and Luangwa