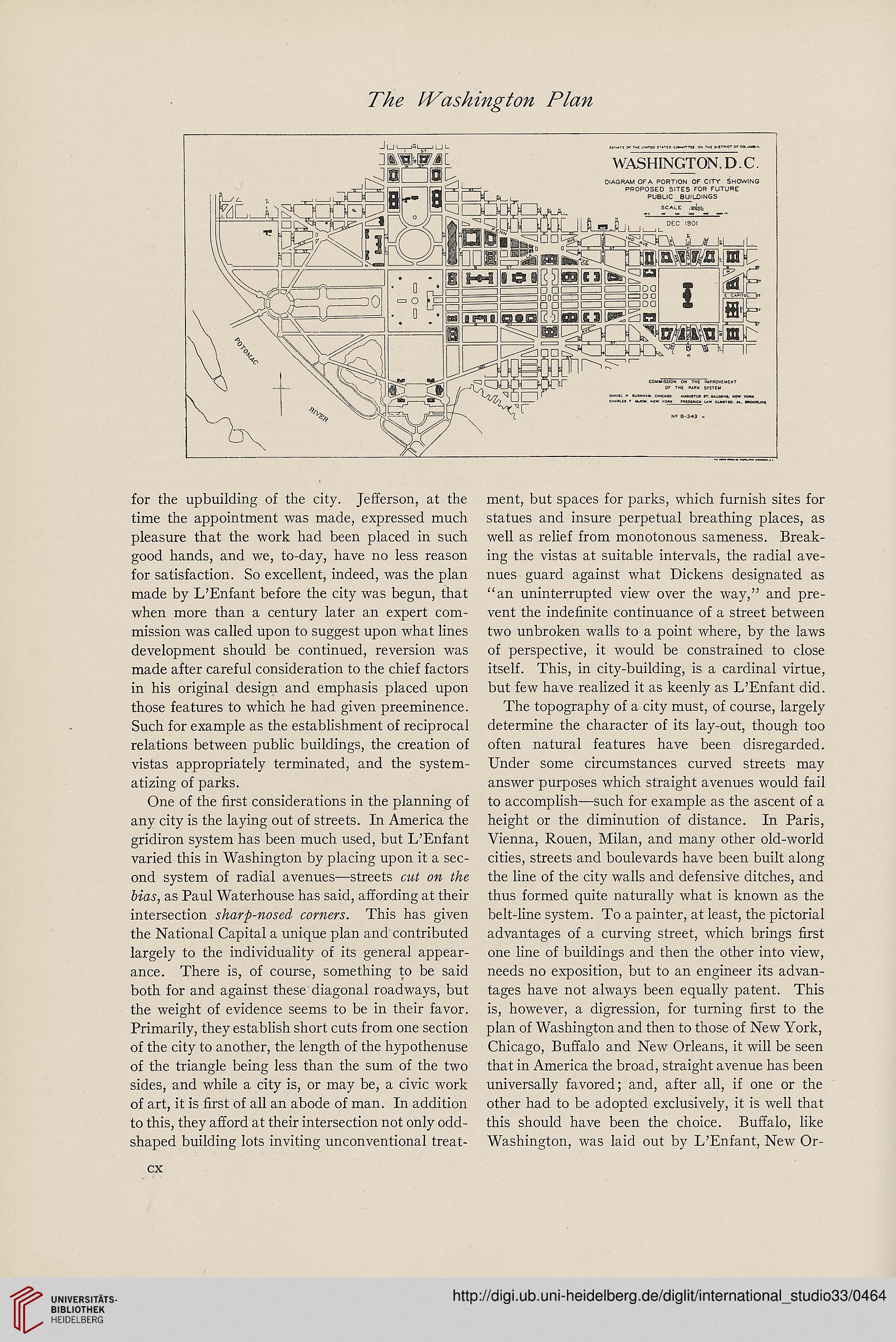

The Washington Plan

for the upbuilding of the city. Jefferson, at the

time the appointment was made, expressed much

pleasure that the work had been placed in such

good hands, and we, to-day, have no less reason

for satisfaction. So excellent, indeed, was the plan

made by L’Enfant before the city was begun, that

when more than a century later an expert com-

mission was called upon to suggest upon what lines

development should be continued, reversion was

made after careful consideration to the chief factors

in his original design and emphasis placed upon

those features to which he had given preeminence.

Such for example as the establishment of reciprocal

relations between public buildings, the creation of

vistas appropriately terminated, and the system-

atizing of parks.

One of the first considerations in the planning of

any city is the laying out of streets. In America the

gridiron system has been much used, but L’Enfant

varied this in Washington by placing upon it a sec-

ond system of radial avenues—streets cut on the

bias, as Paul Waterhouse has said, affording at their

intersection sharp-nosed corners. This has given

the National Capital a unique plan and contributed

largely to the individuality of its general appear-

ance. There is, of course, something to be said

both for and against these diagonal roadways, but

the weight of evidence seems to be in their favor.

Primarily, they establish short cuts from one section

of the city to another, the length of the hypothenuse

of the triangle being less than the sum of the two

sides, and while a city is, or may be, a civic work

of art, it is first of all an abode of man. In addition

to this, they afford at their intersection not only odd-

shaped building lots inviting unconventional treat-

ment, but spaces for parks, which furnish sites for

statues and insure perpetual breathing places, as

well as relief from monotonous sameness. Break-

ing the vistas at suitable intervals, the radial ave-

nues guard against what Dickens designated as

“an uninterrupted view over the way,” and pre-

vent the indefinite continuance of a street between

two unbroken walls to a point where, by the laws

of perspective, it would be constrained to close

itself. This, in city-building, is a cardinal virtue,

but few have realized it as keenly as L’Enfant did.

The topography of a city must, of course, largely

determine the character of its lay-out, though too

often natural features have been disregarded.

Under some circumstances curved streets may

answer purposes which straight avenues would fail

to accomplish—such for example as the ascent of a

height or the diminution of distance. In Paris,

Vienna, Rouen, Milan, and many other old-world

cities, streets and boulevards have been built along

the line of the city walls and defensive ditches, and

thus formed quite naturally what is known as the

belt-line system. To a painter, at least, the pictorial

advantages of a curving street, which brings first

one line of buildings and then the other into view,

needs no exposition, but to an engineer its advan-

tages have not always been equally patent. This

is, however, a digression, for turning first to the

plan of Washington and then to those of New York,

Chicago, Buffalo and New Orleans, it will be seen

that in America the broad, straight avenue has been

universally favored; and, after all, if one or the

other had to be adopted exclusively, it is well that

this should have been the choice. Buffalo, like

Washington, was laid out by L’Enfant, New Or-

cx

for the upbuilding of the city. Jefferson, at the

time the appointment was made, expressed much

pleasure that the work had been placed in such

good hands, and we, to-day, have no less reason

for satisfaction. So excellent, indeed, was the plan

made by L’Enfant before the city was begun, that

when more than a century later an expert com-

mission was called upon to suggest upon what lines

development should be continued, reversion was

made after careful consideration to the chief factors

in his original design and emphasis placed upon

those features to which he had given preeminence.

Such for example as the establishment of reciprocal

relations between public buildings, the creation of

vistas appropriately terminated, and the system-

atizing of parks.

One of the first considerations in the planning of

any city is the laying out of streets. In America the

gridiron system has been much used, but L’Enfant

varied this in Washington by placing upon it a sec-

ond system of radial avenues—streets cut on the

bias, as Paul Waterhouse has said, affording at their

intersection sharp-nosed corners. This has given

the National Capital a unique plan and contributed

largely to the individuality of its general appear-

ance. There is, of course, something to be said

both for and against these diagonal roadways, but

the weight of evidence seems to be in their favor.

Primarily, they establish short cuts from one section

of the city to another, the length of the hypothenuse

of the triangle being less than the sum of the two

sides, and while a city is, or may be, a civic work

of art, it is first of all an abode of man. In addition

to this, they afford at their intersection not only odd-

shaped building lots inviting unconventional treat-

ment, but spaces for parks, which furnish sites for

statues and insure perpetual breathing places, as

well as relief from monotonous sameness. Break-

ing the vistas at suitable intervals, the radial ave-

nues guard against what Dickens designated as

“an uninterrupted view over the way,” and pre-

vent the indefinite continuance of a street between

two unbroken walls to a point where, by the laws

of perspective, it would be constrained to close

itself. This, in city-building, is a cardinal virtue,

but few have realized it as keenly as L’Enfant did.

The topography of a city must, of course, largely

determine the character of its lay-out, though too

often natural features have been disregarded.

Under some circumstances curved streets may

answer purposes which straight avenues would fail

to accomplish—such for example as the ascent of a

height or the diminution of distance. In Paris,

Vienna, Rouen, Milan, and many other old-world

cities, streets and boulevards have been built along

the line of the city walls and defensive ditches, and

thus formed quite naturally what is known as the

belt-line system. To a painter, at least, the pictorial

advantages of a curving street, which brings first

one line of buildings and then the other into view,

needs no exposition, but to an engineer its advan-

tages have not always been equally patent. This

is, however, a digression, for turning first to the

plan of Washington and then to those of New York,

Chicago, Buffalo and New Orleans, it will be seen

that in America the broad, straight avenue has been

universally favored; and, after all, if one or the

other had to be adopted exclusively, it is well that

this should have been the choice. Buffalo, like

Washington, was laid out by L’Enfant, New Or-

cx