mceRtiACionAL

LEAD AND TIN IN A<RT

Tin and lead may be Metals looked upon as In mediaeval Europe

indifferently relegated purely utilitarian things, Iead work is cIoseIy associ"

by us today to the ^ ^ W > reCQrds ated with architecture in

utilitarian stock in trade oi r j rooting, spires, lanterns,

the plumber and tinsmith, in usa9e ln tne arts parapets and gutters, as

but they have a family his- ELIZABETH WHITE we^ as a remarkable variety

tory that not only goes of ornamental detail. Ham-

proudly back to immemorial time, but also in- mering, incision and gilding were used to increase

-eludes many important phases of artistic expres- the beauty of the lead crests and finials on the

sion. When the Prophet Ezekiel rebuked the ridges and summits of Gothic buildings. The

Phoenician merchants of Tyre, some six hundred gilding of the ornamental Ieadwork of St. Cha-

years before the Christian era, for their amassing pelle, the .pierced and painted ridge of the Cathe-

of wealth in the tin and lead trade with Tarshish, dral of Bourges and the spire of the Cathedral of

both metals already had had a long and honorable Amiens are fine examples that come readily to

record of service. Tin mind of the work of

was valued at this

time, chiefly, if not

wholly, as an alloy of

bronze, but lead was

considered an import-

ant metal in itself, be-

cause of its malleabil-

ity and its low heat of

fusion, which rendered

its working compara-

tively easy.

One might hit all

the high spots of the

old Mediterranean

civilizations and those

of Asia Minor and find

lead in statuary or or-

nament each time. A

prehistoric statue

found in Egypt marks

the early period of its

use there, continued

the' mediaeval plomb-

ier. Indeed, much of

this handicraft resem-

bled that of the gold-

smith on a colossal

scale and formed an

art quite apart from

the working of wood or

stone.

Practical consider-

ations, no doubt, in-

fluenced the choice of

lead, since it is. not af-

fected by exposure

and so formed an ideal

material for roofing.

Moreover, the ease

with which the roof

and its filigree of lead-

work could be melted

up and poured down

on undesirable people

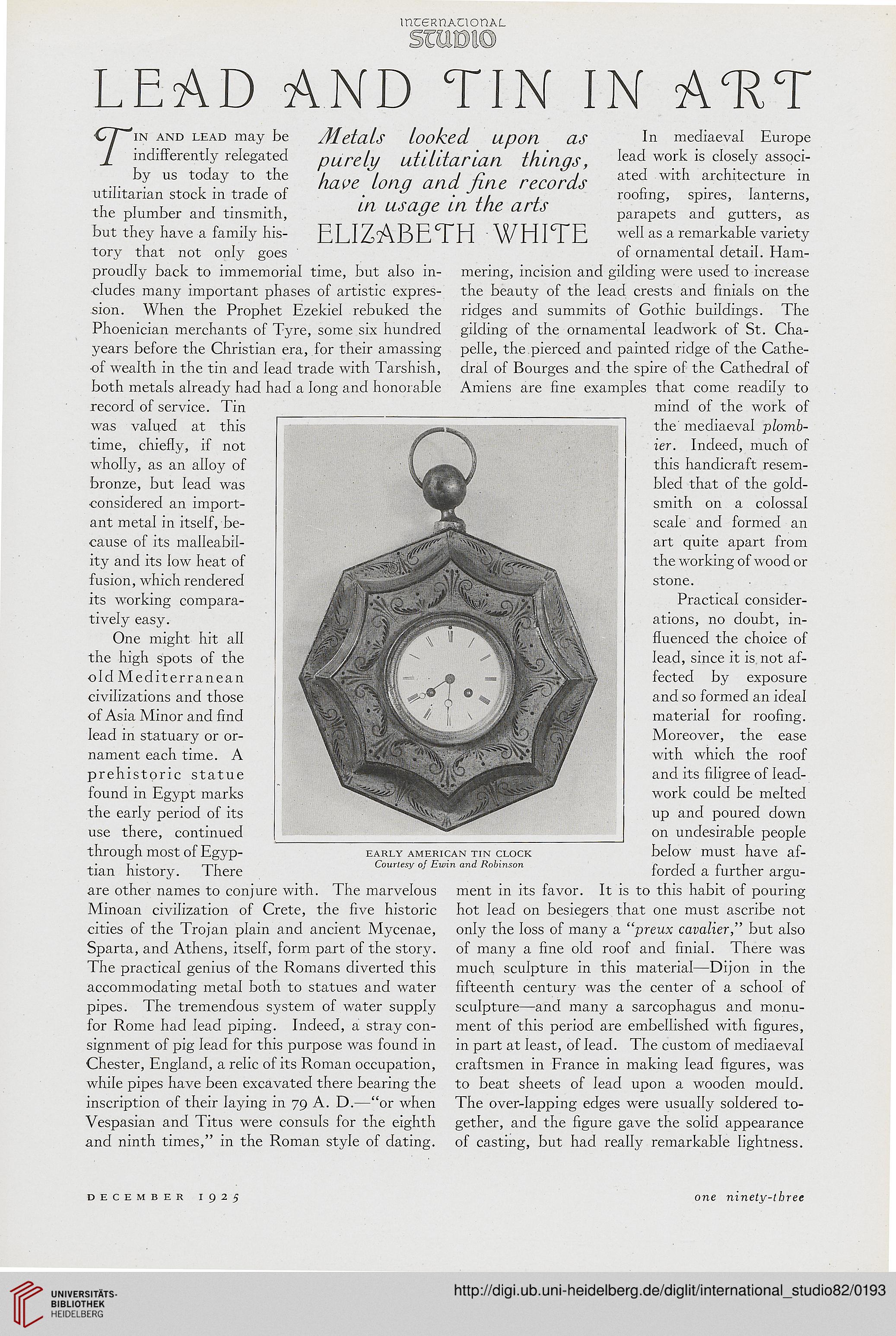

through most of Egyp- early American tin clock below must have af-

7 • f-r^r Courtesy of Ewin and Robinson r j r r , t

tian history. There ' forded a iurther argu-

are other names to conjure with. The marvelous ment in its favor. It is to this habit of pouring

Minoan civilization of Crete, the five historic hot lead on besiegers that one must ascribe not

cities of the Trojan plain and ancient Mycenae, only the loss of many a "preux cavalier," but also

Sparta, and Athens, itself, form part of the story, of many a fine old roof and finial. There was

The practical genius of the Romans diverted this much sculpture in this material—Dijon in the

accommodating metal both to statues and water fifteenth century was the center of a school of

pipes. The tremendous system of water supply sculpture—and many a sarcophagus and monu-

for Rome had lead piping. Indeed, a stray con- ment of this period are embellished with figures,

signment of pig lead for this purpose was found in in part at least, of lead. The custom of mediaeval

Chester, England, a relic of its Roman occupation, craftsmen in France in making lead figures, was

while pipes have been excavated there bearing the to beat sheets of lead upon a wooden mould,

inscription of their laying in 79 A. D.—"or when The over-lapping edges were usually soldered to-

Vespasian and Titus were consuls for the eighth gethcr, and the figure gave the solid appearance

and ninth times," in the Roman style of dating, of casting, but had really remarkable lightness.

december i 9 2 5

one ninety-three

LEAD AND TIN IN A<RT

Tin and lead may be Metals looked upon as In mediaeval Europe

indifferently relegated purely utilitarian things, Iead work is cIoseIy associ"

by us today to the ^ ^ W > reCQrds ated with architecture in

utilitarian stock in trade oi r j rooting, spires, lanterns,

the plumber and tinsmith, in usa9e ln tne arts parapets and gutters, as

but they have a family his- ELIZABETH WHITE we^ as a remarkable variety

tory that not only goes of ornamental detail. Ham-

proudly back to immemorial time, but also in- mering, incision and gilding were used to increase

-eludes many important phases of artistic expres- the beauty of the lead crests and finials on the

sion. When the Prophet Ezekiel rebuked the ridges and summits of Gothic buildings. The

Phoenician merchants of Tyre, some six hundred gilding of the ornamental Ieadwork of St. Cha-

years before the Christian era, for their amassing pelle, the .pierced and painted ridge of the Cathe-

of wealth in the tin and lead trade with Tarshish, dral of Bourges and the spire of the Cathedral of

both metals already had had a long and honorable Amiens are fine examples that come readily to

record of service. Tin mind of the work of

was valued at this

time, chiefly, if not

wholly, as an alloy of

bronze, but lead was

considered an import-

ant metal in itself, be-

cause of its malleabil-

ity and its low heat of

fusion, which rendered

its working compara-

tively easy.

One might hit all

the high spots of the

old Mediterranean

civilizations and those

of Asia Minor and find

lead in statuary or or-

nament each time. A

prehistoric statue

found in Egypt marks

the early period of its

use there, continued

the' mediaeval plomb-

ier. Indeed, much of

this handicraft resem-

bled that of the gold-

smith on a colossal

scale and formed an

art quite apart from

the working of wood or

stone.

Practical consider-

ations, no doubt, in-

fluenced the choice of

lead, since it is. not af-

fected by exposure

and so formed an ideal

material for roofing.

Moreover, the ease

with which the roof

and its filigree of lead-

work could be melted

up and poured down

on undesirable people

through most of Egyp- early American tin clock below must have af-

7 • f-r^r Courtesy of Ewin and Robinson r j r r , t

tian history. There ' forded a iurther argu-

are other names to conjure with. The marvelous ment in its favor. It is to this habit of pouring

Minoan civilization of Crete, the five historic hot lead on besiegers that one must ascribe not

cities of the Trojan plain and ancient Mycenae, only the loss of many a "preux cavalier," but also

Sparta, and Athens, itself, form part of the story, of many a fine old roof and finial. There was

The practical genius of the Romans diverted this much sculpture in this material—Dijon in the

accommodating metal both to statues and water fifteenth century was the center of a school of

pipes. The tremendous system of water supply sculpture—and many a sarcophagus and monu-

for Rome had lead piping. Indeed, a stray con- ment of this period are embellished with figures,

signment of pig lead for this purpose was found in in part at least, of lead. The custom of mediaeval

Chester, England, a relic of its Roman occupation, craftsmen in France in making lead figures, was

while pipes have been excavated there bearing the to beat sheets of lead upon a wooden mould,

inscription of their laying in 79 A. D.—"or when The over-lapping edges were usually soldered to-

Vespasian and Titus were consuls for the eighth gethcr, and the figure gave the solid appearance

and ninth times," in the Roman style of dating, of casting, but had really remarkable lightness.

december i 9 2 5

one ninety-three