mceRHAcionAL

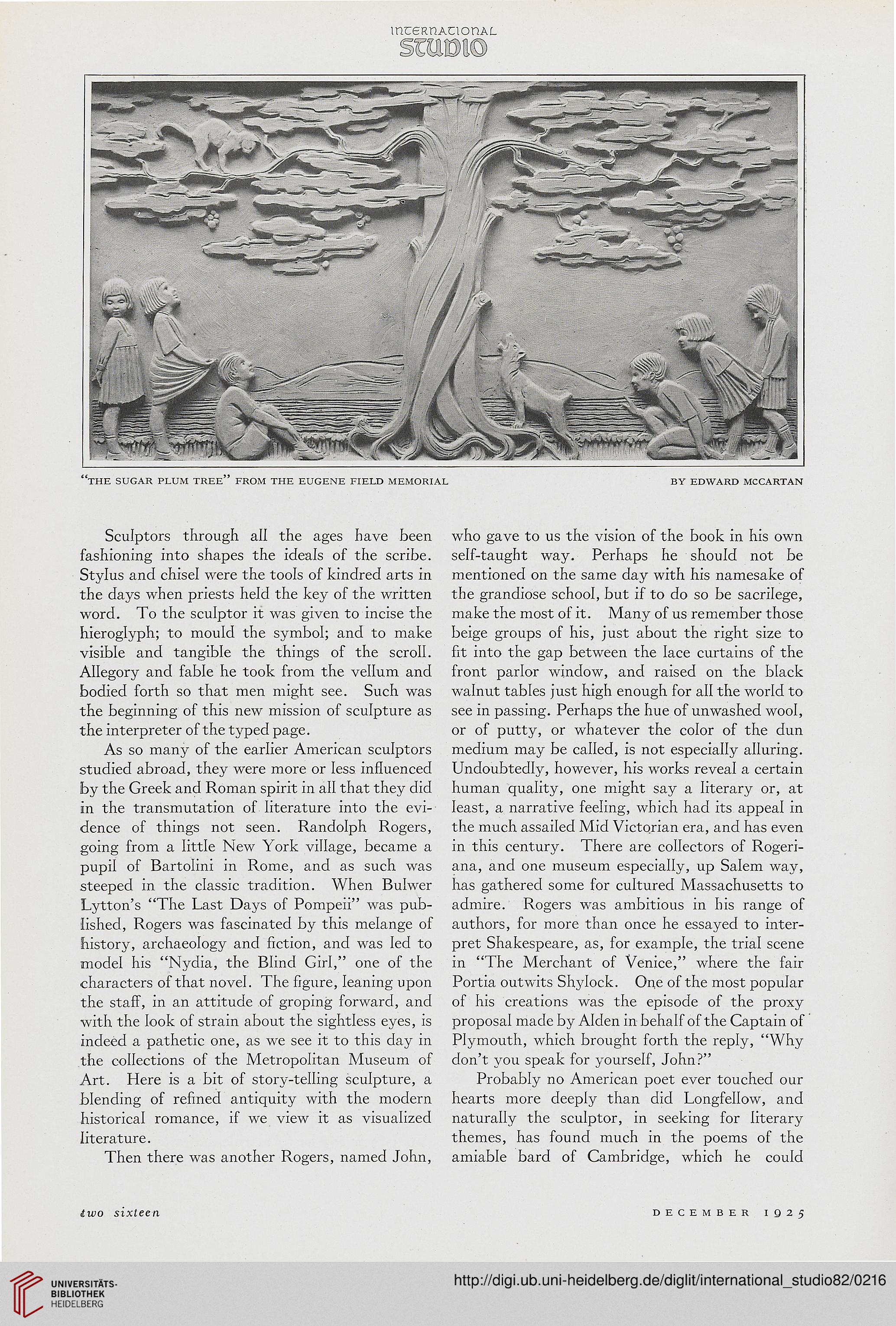

"THE SUGAR PLUM TREE" FROM THE EUGENE FIELD MEMORIAL BY EDWARD MCCARTAN

Sculptors through all the ages have been

fashioning into shapes the ideals of the scribe.

Stylus and chisel were the tools of kindred arts in

the days when priests held the key of the written

word. To the sculptor it was given to incise the

hieroglyph; to mould the symbol; and to make

visible and tangible the things of the scroll.

Allegory and fable he took from the vellum and

bodied forth so that men might see. Such was

the beginning of this new mission of sculpture as

the interpreter of the typed page.

As so many of the earlier American sculptors

studied abroad, they were more or less influenced

by the Greek and Roman spirit in all that they did

in the transmutation of literature into the evi-

dence of things not seen. Randolph Rogers,

going from a little New York village, became a

pupil of Bartolini in Rome, and as such was

steeped in the classic tradition. When Bulwer

Lytton's "The Last Days of Pompeii" was pub-

lished, Rogers was fascinated by this melange of

history, archaeology and fiction, and was led to

model his "Nydia, the Blind Girl," one of the

characters of that novel. The figure, leaning upon

the staff, in an attitude of groping forward, and

with the look of strain about the sightless eyes, is

indeed a pathetic one, as we see it to this day in

the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of

Art. Here is a bit of story-telling sculpture, a

blending of refined antiquity with the modern

historical romance, if we view it as visualized

literature.

Then there was another Rogers, named John,

who gave to us the vision of the book in his own

self-taught way. Perhaps he should not be

mentioned on the same day with his namesake of

the grandiose school, but if to do so be sacrilege,

make the most of it. Many of us remember those

beige groups of his, just about the right size to

fit into the gap between the lace curtains of the

front parlor window, and raised on the black

walnut tables just high enough for all the world to

see in passing. Perhaps the hue of unwashed wool,

or of putty, or whatever the color of the dun

medium may be called, is not especially alluring.

Undoubtedly, however, his works reveal a certain

human quality, one might say a literary or, at

least, a narrative feeling, which had its appeal in

the much assailed Mid Victorian era, and has even

in this century. There are collectors of Rogeri-

ana, and one museum especially, up Salem way,

has gathered some for cultured Massachusetts to

admire. Rogers was ambitious in his range of

authors, for more than once he essayed to inter-

pret Shakespeare, as, for example, the trial scene

in "The Merchant of Venice," where the fair

Portia outwits Shylock. Oue of the most popular

of his creations was the episode of the proxy

proposal made by Alden in behalf of the Captain of

Plymouth, which brought forth the reply, "Why

don't you speak for yourself, John?"

Probably no American poet ever touched our

hearts more deeply than did Longfellow, and

naturally the sculptor, in seeking for literary

themes, has found much in the poems of the

amiable bard of Cambridge, which he could

two sixteen

DECEMBER I 9 25

"THE SUGAR PLUM TREE" FROM THE EUGENE FIELD MEMORIAL BY EDWARD MCCARTAN

Sculptors through all the ages have been

fashioning into shapes the ideals of the scribe.

Stylus and chisel were the tools of kindred arts in

the days when priests held the key of the written

word. To the sculptor it was given to incise the

hieroglyph; to mould the symbol; and to make

visible and tangible the things of the scroll.

Allegory and fable he took from the vellum and

bodied forth so that men might see. Such was

the beginning of this new mission of sculpture as

the interpreter of the typed page.

As so many of the earlier American sculptors

studied abroad, they were more or less influenced

by the Greek and Roman spirit in all that they did

in the transmutation of literature into the evi-

dence of things not seen. Randolph Rogers,

going from a little New York village, became a

pupil of Bartolini in Rome, and as such was

steeped in the classic tradition. When Bulwer

Lytton's "The Last Days of Pompeii" was pub-

lished, Rogers was fascinated by this melange of

history, archaeology and fiction, and was led to

model his "Nydia, the Blind Girl," one of the

characters of that novel. The figure, leaning upon

the staff, in an attitude of groping forward, and

with the look of strain about the sightless eyes, is

indeed a pathetic one, as we see it to this day in

the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of

Art. Here is a bit of story-telling sculpture, a

blending of refined antiquity with the modern

historical romance, if we view it as visualized

literature.

Then there was another Rogers, named John,

who gave to us the vision of the book in his own

self-taught way. Perhaps he should not be

mentioned on the same day with his namesake of

the grandiose school, but if to do so be sacrilege,

make the most of it. Many of us remember those

beige groups of his, just about the right size to

fit into the gap between the lace curtains of the

front parlor window, and raised on the black

walnut tables just high enough for all the world to

see in passing. Perhaps the hue of unwashed wool,

or of putty, or whatever the color of the dun

medium may be called, is not especially alluring.

Undoubtedly, however, his works reveal a certain

human quality, one might say a literary or, at

least, a narrative feeling, which had its appeal in

the much assailed Mid Victorian era, and has even

in this century. There are collectors of Rogeri-

ana, and one museum especially, up Salem way,

has gathered some for cultured Massachusetts to

admire. Rogers was ambitious in his range of

authors, for more than once he essayed to inter-

pret Shakespeare, as, for example, the trial scene

in "The Merchant of Venice," where the fair

Portia outwits Shylock. Oue of the most popular

of his creations was the episode of the proxy

proposal made by Alden in behalf of the Captain of

Plymouth, which brought forth the reply, "Why

don't you speak for yourself, John?"

Probably no American poet ever touched our

hearts more deeply than did Longfellow, and

naturally the sculptor, in seeking for literary

themes, has found much in the poems of the

amiable bard of Cambridge, which he could

two sixteen

DECEMBER I 9 25