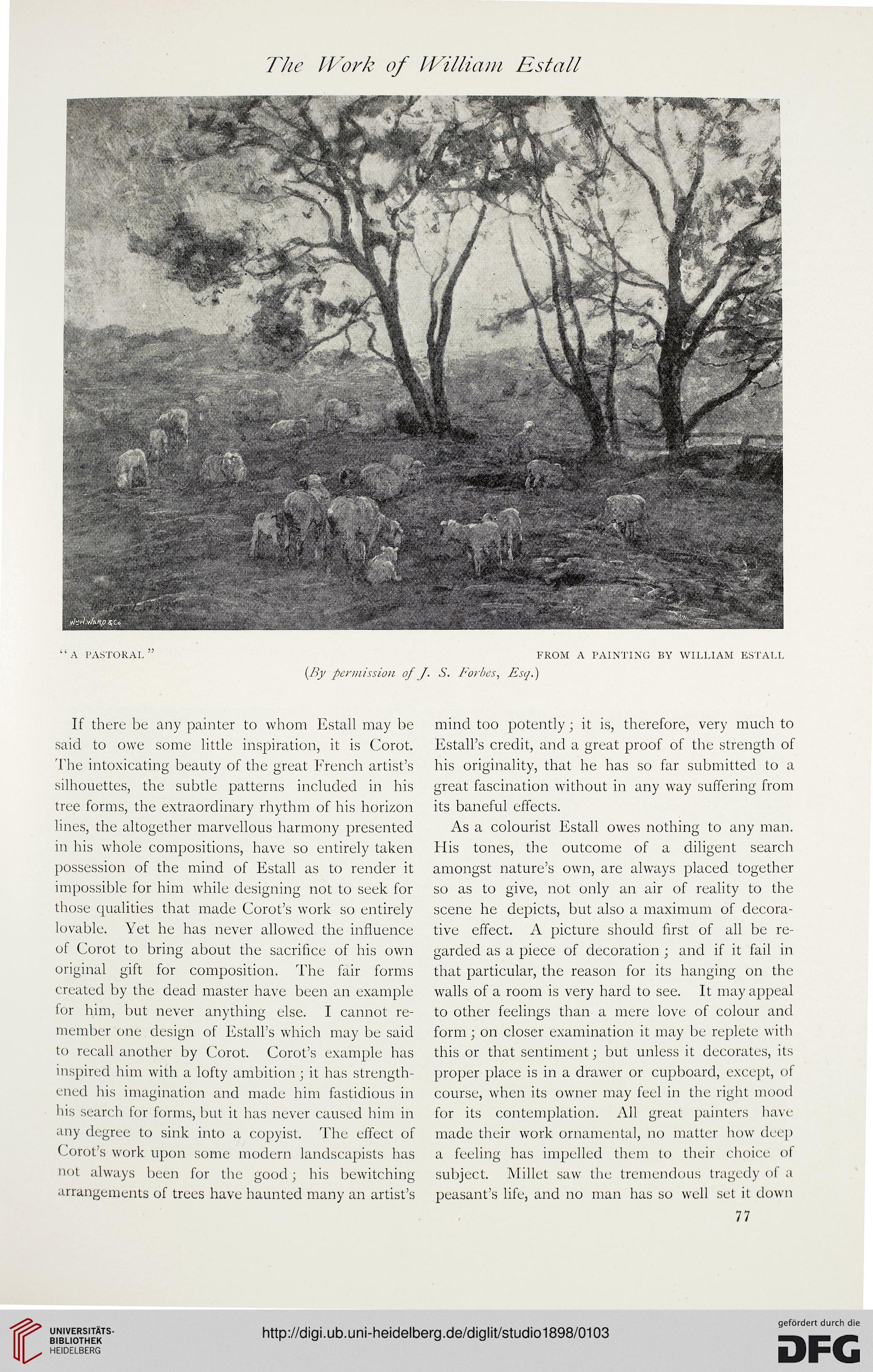

llic Work of William Estall

If there be any painter to whom Estall may be

said to owe some little inspiration, it is Corot.

The intoxicating beauty of the great French artist's

silhouettes, the subtle patterns included in his

tree forms, the extraordinary rhythm of his horizon

lines, the altogether marvellous harmony presented

in his whole compositions, have so entirely taken

possession of the mind of Estall as to render it

impossible for him while designing not to seek for

those qualities that made Corot's work so entirely

lovable. Yet he has never allowed the influence

of Corot to bring about the sacrifice of his own

original gift for composition. The fair forms

created by the dead master have been an example

for him, but never anything else. I cannot re-

member one design of Estall's which may be said

to recall another by Corot. Corot's example has

inspired him with a lofty ambition ; it has strength-

ened his imagination and made him fastidious in

his search for forms, but it has never caused him in

any degree to sink into a copyist. The effect of

Corot's work upon some modern landscapists has

not always been for the good; his bewitching

arrangements of trees have haunted many an artist's

mind too potently; it is, therefore, very much to

Estall's credit, and a great proof of the strength of

his originality, that he has so far submitted to a

great fascination without in any way suffering from

its baneful effects.

As a colourist Estall owes nothing to any man.

His tones, the outcome of a diligent search

amongst nature's own, are always placed together

so as to give, not only an air of reality to the

scene he depicts, but also a maximum of decora-

tive effect. A picture should first of all be re-

garded as a piece of decoration ; and if it fail in

that particular, the reason for its hanging on the

walls of a room is very hard to see. It may appeal

to other feelings than a mere love of colour and

form ; on closer examination it may be replete with

this or that sentiment; but unless it decorates, its

proper place is in a drawer or cupboard, except, of

course, when its owner may feel in the right mood

for its contemplation. All great painters have

made their work ornamental, no matter how deep

a feeling has impelled them to their choice oi

subject. Millet saw the tremendous tragedy oi a

peasant's life, and no man has so well set it down

77

If there be any painter to whom Estall may be

said to owe some little inspiration, it is Corot.

The intoxicating beauty of the great French artist's

silhouettes, the subtle patterns included in his

tree forms, the extraordinary rhythm of his horizon

lines, the altogether marvellous harmony presented

in his whole compositions, have so entirely taken

possession of the mind of Estall as to render it

impossible for him while designing not to seek for

those qualities that made Corot's work so entirely

lovable. Yet he has never allowed the influence

of Corot to bring about the sacrifice of his own

original gift for composition. The fair forms

created by the dead master have been an example

for him, but never anything else. I cannot re-

member one design of Estall's which may be said

to recall another by Corot. Corot's example has

inspired him with a lofty ambition ; it has strength-

ened his imagination and made him fastidious in

his search for forms, but it has never caused him in

any degree to sink into a copyist. The effect of

Corot's work upon some modern landscapists has

not always been for the good; his bewitching

arrangements of trees have haunted many an artist's

mind too potently; it is, therefore, very much to

Estall's credit, and a great proof of the strength of

his originality, that he has so far submitted to a

great fascination without in any way suffering from

its baneful effects.

As a colourist Estall owes nothing to any man.

His tones, the outcome of a diligent search

amongst nature's own, are always placed together

so as to give, not only an air of reality to the

scene he depicts, but also a maximum of decora-

tive effect. A picture should first of all be re-

garded as a piece of decoration ; and if it fail in

that particular, the reason for its hanging on the

walls of a room is very hard to see. It may appeal

to other feelings than a mere love of colour and

form ; on closer examination it may be replete with

this or that sentiment; but unless it decorates, its

proper place is in a drawer or cupboard, except, of

course, when its owner may feel in the right mood

for its contemplation. All great painters have

made their work ornamental, no matter how deep

a feeling has impelled them to their choice oi

subject. Millet saw the tremendous tragedy oi a

peasant's life, and no man has so well set it down

77