Early Scandinavian Wood-(. %arvings

began to fall to pieces, so that the village priest,

Pastor Arneston, was glad (on Aladdin's principle

of " new lamps for old ") to hand over this precious

relic of antiquity to the Copenhagen Museum, and

to receive in exchange a new oaken door and two

altar candlesticks. The late Prof. George Stephens,

the world renowned Runic scholar of Copenhagen,

has described this door very fully in the Archceo-

logia Scotica (vol. v. 1873, p. 249) of the Society

of Antiquaries of Scotland. He explains that the

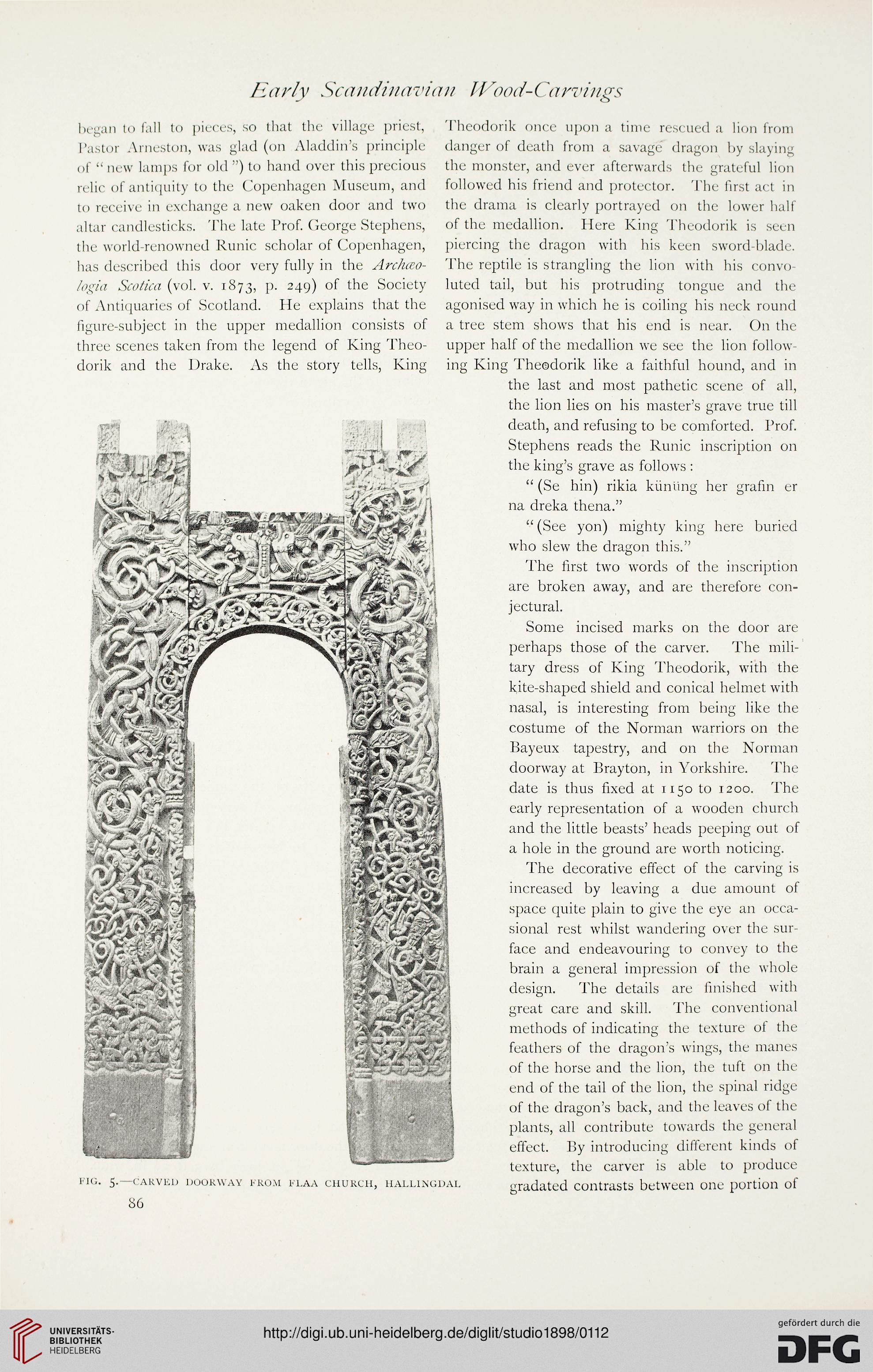

figure-subject in the upper medallion consists of

three scenes taken from the legend of King Theo-

dorik and the Drake. As the story tells, King

FIG. 5.—CARVED DOORWAY FROM FLAA CHURCH, HALLINGDAL

86

Theodorik once upon a time rescued a lion from

danger of death from a savage dragon by slaying

the monster, and ever afterwards the grateful lion

followed his friend and protector. The first act in

the drama is clearly portrayed on the lower half

of the medallion. Here King Theodorik is seen

piercing the dragon with his keen sword-blade.

The reptile is strangling the lion with his convo

luted tail, but his protruding tongue and the

agonised way in which he is coiling his neck round

a tree stem shows that his end is near. On the

upper half of the medallion we see the lion follow-

ing King Theodorik like a faithful hound, and in

the last and most pathetic scene of all,

the lion lies on his master's grave true till

death, and refusing to be comforted. Prof.

Stephens reads the Runic inscription on

the king's grave as follows :

" (Se hin) rikia kiinling her grafin er

na dreka thena."

"(See yon) mighty king here buried

who slew the dragon this."

The first twTo words of the inscription

are broken away, and are therefore con-

jectural.

Some incised marks on the door are

perhaps those of the carver. The mili-

tary dress of King Theodorik, with the

k,ite-shaped shield and conical helmet with

nasal, is interesting from being like the

costume of the Norman warriors on the

Bayeux tapestry, and on the Norman

doorway at Brayton, in Yorkshire. The

date is thus fixed at n50 to 1200. The

early representation of a wooden church

and the little beasts' heads peeping out of

a hole in the ground are worth noticing.

The decorative effect of the carving is

increased by leaving a due amount of

space quite plain to give the eye an occa-

sional rest whilst wandering over the sur-

face and endeavouring to convey to the

brain a general impression of the whole

design. The details are finished with

great care and skill. The conventional

methods of indicating the texture ot the

feathers of the dragons wings, the manes

of the horse and the lion, the tuft on the

end of the tail of the lion, the spinal ridge

of the dragon's back, and the leaves of the

plants, all contribute towards the general

effect. By introducing different kinds of

texture, the carver is able to produce

gradated contrasts between one portion ot

began to fall to pieces, so that the village priest,

Pastor Arneston, was glad (on Aladdin's principle

of " new lamps for old ") to hand over this precious

relic of antiquity to the Copenhagen Museum, and

to receive in exchange a new oaken door and two

altar candlesticks. The late Prof. George Stephens,

the world renowned Runic scholar of Copenhagen,

has described this door very fully in the Archceo-

logia Scotica (vol. v. 1873, p. 249) of the Society

of Antiquaries of Scotland. He explains that the

figure-subject in the upper medallion consists of

three scenes taken from the legend of King Theo-

dorik and the Drake. As the story tells, King

FIG. 5.—CARVED DOORWAY FROM FLAA CHURCH, HALLINGDAL

86

Theodorik once upon a time rescued a lion from

danger of death from a savage dragon by slaying

the monster, and ever afterwards the grateful lion

followed his friend and protector. The first act in

the drama is clearly portrayed on the lower half

of the medallion. Here King Theodorik is seen

piercing the dragon with his keen sword-blade.

The reptile is strangling the lion with his convo

luted tail, but his protruding tongue and the

agonised way in which he is coiling his neck round

a tree stem shows that his end is near. On the

upper half of the medallion we see the lion follow-

ing King Theodorik like a faithful hound, and in

the last and most pathetic scene of all,

the lion lies on his master's grave true till

death, and refusing to be comforted. Prof.

Stephens reads the Runic inscription on

the king's grave as follows :

" (Se hin) rikia kiinling her grafin er

na dreka thena."

"(See yon) mighty king here buried

who slew the dragon this."

The first twTo words of the inscription

are broken away, and are therefore con-

jectural.

Some incised marks on the door are

perhaps those of the carver. The mili-

tary dress of King Theodorik, with the

k,ite-shaped shield and conical helmet with

nasal, is interesting from being like the

costume of the Norman warriors on the

Bayeux tapestry, and on the Norman

doorway at Brayton, in Yorkshire. The

date is thus fixed at n50 to 1200. The

early representation of a wooden church

and the little beasts' heads peeping out of

a hole in the ground are worth noticing.

The decorative effect of the carving is

increased by leaving a due amount of

space quite plain to give the eye an occa-

sional rest whilst wandering over the sur-

face and endeavouring to convey to the

brain a general impression of the whole

design. The details are finished with

great care and skill. The conventional

methods of indicating the texture ot the

feathers of the dragons wings, the manes

of the horse and the lion, the tuft on the

end of the tail of the lion, the spinal ridge

of the dragon's back, and the leaves of the

plants, all contribute towards the general

effect. By introducing different kinds of

texture, the carver is able to produce

gradated contrasts between one portion ot