The Cha-no-yu Pottery of Japan

rampant, the tea ceremony was cultivated as a foil

to and as a protest against the evil tendencies of

the time, and was the means by which the minds

of those taking part in it might be turned from the

clash of arms, from the display of wealth, and

inclined towards the elevating influences of pure

aestheticism ; and it was fitting that all the adjuncts

to the ceremony should be so formed as to be con-

ducive to that end.

Rikiu, the founder of the most popular school

of Cha-noyu, being quizzed upon the supposed

elaborate secrets of the ceremony, is stated to have

replied,* “Well, there is no particular secret in the

ceremony save in making tea agreeable to the

palate, in piling charcoal on the brazier so as to

make a good fire for boiling the water, in arranging

flowers in a natural way and in making things

cool in summer and warm in winter.” Somewhat

disappointed with the apparently commonplace

explanation, the enquirer said, “ Who on earth

does not know how to do that ? ” Rikiu’s happy

retort was, “Well, if you know it, do it.”

The main influence at work in the foundation of

the tea ceremony was of a religious nature. The

teaching of Laotze, a contemporary of Confucius,

and the influence of Zenism—a branch of Buddhism

in which is incorporated much of the spirit of

the Laotze philosophy—are largely responsible for

the characteristics which signalise every detail

of the ceremony. They had, in the thirteenth

century and onwards, a potent influence on the

thoughts and, indeed, on the very life of the

Japanese nation—an influence of so beneficent a

character that it may truly be said that its purest

ideals may be traced directly thereto. Luxury was

turned to refinement, the abasement of self was

taught as the highest virtue, simplicity as

its chief charm. Laws of art were derived

from a close study of the life of nature,

and an intimate sympathy with it in all

its phases. The ideals of the painter and

the poet were filled with Romanticism in

its purest and most elevating form—in its

exaltation of spirit above mere naturalism.

Never, perhaps, in the world’s history had

the doctrine of high thought and simple

living become so materialised as under

the influence of that cult.

The tea-room, following the rules laid

down by the masters, was extremely small

and most unpretentious in character. But

every detail in its least particular was

* Prof. Takashima Steta in “ The Far East.”

32

planned with the greatest care. Okakura-Kakuzo

in his charming “Book of Tea” says: “Even

in the daytime the light of the room is subdued,

for the low eaves of the slanting roof admit but

few of the sun’s rays. Everything is sober in

tint from the ceiling to the floor; the guests

themselves have carefully chosen garments of

unobtrusive colours. The mellowness of age is

over all, everything suggestive of recent acquire-

ment being tabooed save only the one note of

contrast furnished by the bamboo dipper and the

linen napkin, both immaculately white and new.

However faded the tea-room and the tea equipage

may seem, everything is absolutely clean. Not a

particle of dust will be found in the darkest corner,

for if any exists, the host is not a tea master. . . .

Rikiu was watching his son Shoan as he swept and

watered the garden path. ‘ Not clean enough,’

said Rikiu, when Shoan had finished his task, and

bade him try again. After a weary hour the son

hurried to Rikiu : ‘ Father, there is nothing more

to be done. The steps have been washed for the

third time, the stone lanterns and the trees are well

sprinkled with water, moss and lichens are shining

with the fresh verdure ; not a twig, not a leaf have

I left on the ground.’ ‘ Young fool,’ chides the tea

master, 1 that is not the way a garden path should

be swept.’ Saying this, Rikiu stepped into the

garden, shook a tree, scattered over the garden

gold and crimson leaves, scraps of the brocade of

autumn. What Rikiu demanded was not cleanli-

ness alone but the beautiful and natural also.”

In our investigations of the characteristics of the

pottery utensils which played so important a part

in this ceremony, it is necessary for us continually

to bear in mind the spirit of simplicity which

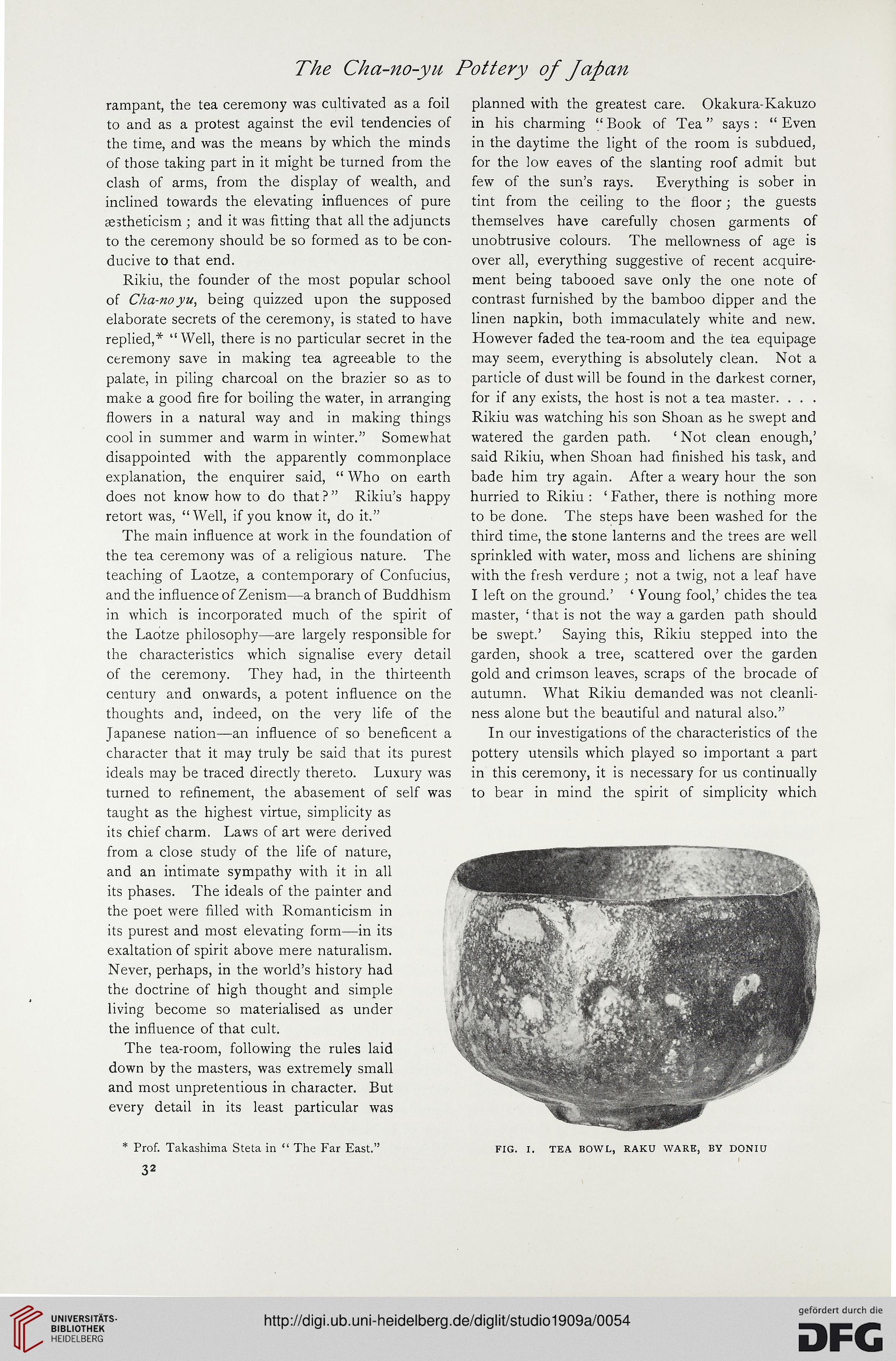

FIG. I. TEA BOWL, RAKU WARE, BY DONIU

rampant, the tea ceremony was cultivated as a foil

to and as a protest against the evil tendencies of

the time, and was the means by which the minds

of those taking part in it might be turned from the

clash of arms, from the display of wealth, and

inclined towards the elevating influences of pure

aestheticism ; and it was fitting that all the adjuncts

to the ceremony should be so formed as to be con-

ducive to that end.

Rikiu, the founder of the most popular school

of Cha-noyu, being quizzed upon the supposed

elaborate secrets of the ceremony, is stated to have

replied,* “Well, there is no particular secret in the

ceremony save in making tea agreeable to the

palate, in piling charcoal on the brazier so as to

make a good fire for boiling the water, in arranging

flowers in a natural way and in making things

cool in summer and warm in winter.” Somewhat

disappointed with the apparently commonplace

explanation, the enquirer said, “ Who on earth

does not know how to do that ? ” Rikiu’s happy

retort was, “Well, if you know it, do it.”

The main influence at work in the foundation of

the tea ceremony was of a religious nature. The

teaching of Laotze, a contemporary of Confucius,

and the influence of Zenism—a branch of Buddhism

in which is incorporated much of the spirit of

the Laotze philosophy—are largely responsible for

the characteristics which signalise every detail

of the ceremony. They had, in the thirteenth

century and onwards, a potent influence on the

thoughts and, indeed, on the very life of the

Japanese nation—an influence of so beneficent a

character that it may truly be said that its purest

ideals may be traced directly thereto. Luxury was

turned to refinement, the abasement of self was

taught as the highest virtue, simplicity as

its chief charm. Laws of art were derived

from a close study of the life of nature,

and an intimate sympathy with it in all

its phases. The ideals of the painter and

the poet were filled with Romanticism in

its purest and most elevating form—in its

exaltation of spirit above mere naturalism.

Never, perhaps, in the world’s history had

the doctrine of high thought and simple

living become so materialised as under

the influence of that cult.

The tea-room, following the rules laid

down by the masters, was extremely small

and most unpretentious in character. But

every detail in its least particular was

* Prof. Takashima Steta in “ The Far East.”

32

planned with the greatest care. Okakura-Kakuzo

in his charming “Book of Tea” says: “Even

in the daytime the light of the room is subdued,

for the low eaves of the slanting roof admit but

few of the sun’s rays. Everything is sober in

tint from the ceiling to the floor; the guests

themselves have carefully chosen garments of

unobtrusive colours. The mellowness of age is

over all, everything suggestive of recent acquire-

ment being tabooed save only the one note of

contrast furnished by the bamboo dipper and the

linen napkin, both immaculately white and new.

However faded the tea-room and the tea equipage

may seem, everything is absolutely clean. Not a

particle of dust will be found in the darkest corner,

for if any exists, the host is not a tea master. . . .

Rikiu was watching his son Shoan as he swept and

watered the garden path. ‘ Not clean enough,’

said Rikiu, when Shoan had finished his task, and

bade him try again. After a weary hour the son

hurried to Rikiu : ‘ Father, there is nothing more

to be done. The steps have been washed for the

third time, the stone lanterns and the trees are well

sprinkled with water, moss and lichens are shining

with the fresh verdure ; not a twig, not a leaf have

I left on the ground.’ ‘ Young fool,’ chides the tea

master, 1 that is not the way a garden path should

be swept.’ Saying this, Rikiu stepped into the

garden, shook a tree, scattered over the garden

gold and crimson leaves, scraps of the brocade of

autumn. What Rikiu demanded was not cleanli-

ness alone but the beautiful and natural also.”

In our investigations of the characteristics of the

pottery utensils which played so important a part

in this ceremony, it is necessary for us continually

to bear in mind the spirit of simplicity which

FIG. I. TEA BOWL, RAKU WARE, BY DONIU