The Cha-no-yu Pottery of Japan

controlled the function in its every detail,

and to remember that no single portion

of its ritual, no detail of its accessories, is

too insignificant to pass unnoticed.

One of the characteristics which first

strike the observer is the absence of

painted decoration on the great majority

of examples which come before him. But,

occasionally, a water jar or a tea bowl is

found with an inscription upon it, or a

few touches of colour suggestive of bird

or plant-life. It may easily be understood,

however, that an elaborately decorated

piece of pottery would be entirely out of

place in a room in which everything was

reduced to its simplest form; one slight

sketch to hang in the recess, one vase of

flowers simply and naturally arranged,

forming the sole ornamentation. And it

is doubtful if the painter’s art when applied

to pottery does not to a certain extent

clash with the qualities which rightly

belong to the potter’s craft. Painter’s

work is not essential to the completion of

a perfect piece of pottery. It adds nothing

to its use, and, unless it be subordinate,

rather detracts from the interest attaching

to those methods of manufacture in which the

truest art of the potter lies. The charm of Cha-no-yu

pottery must be found in those details essentially

necessary to its production. We have seen how in

the tea bowl by Doniu the chief items of interest

are its form and the nature of the clay of which

it is made and of the glaze with which it is covered.

The same observations apply to wares of old Seto,

of Hagi, of Shigaraki, of Iga, of Ohi, of Karatsu, of

Tamba, and of numerous other centres in which

Cha-no-yu wares were produced. But the astonish-

ing thing is, that in spite of the common absence

of applied decoration, individuality may be traced

in almost every example we take in hand. Differ-

ences in the character of the clay, differences in

form or in the treatment of the enamelled glazes

continually strike us. Our interest in such details

is awakened and certain subtleties in one or

other of the potter’s operations which are not at

first apparent become after a time more readily

distinguishable. We begin to appreciate the

curious coarse material employed sometimes by

the Shigaraki potters in which little particles of

quartz sand are embedded, the hard fine stoneware

of Bizen, the beautifully-prepared material of the

Seto potters, or the red and grey varieties of

Satsuma earths. We are able to distinguish the

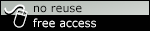

FIG. 2. TEA BOWL, MATSUMOTO, HAGI WARE

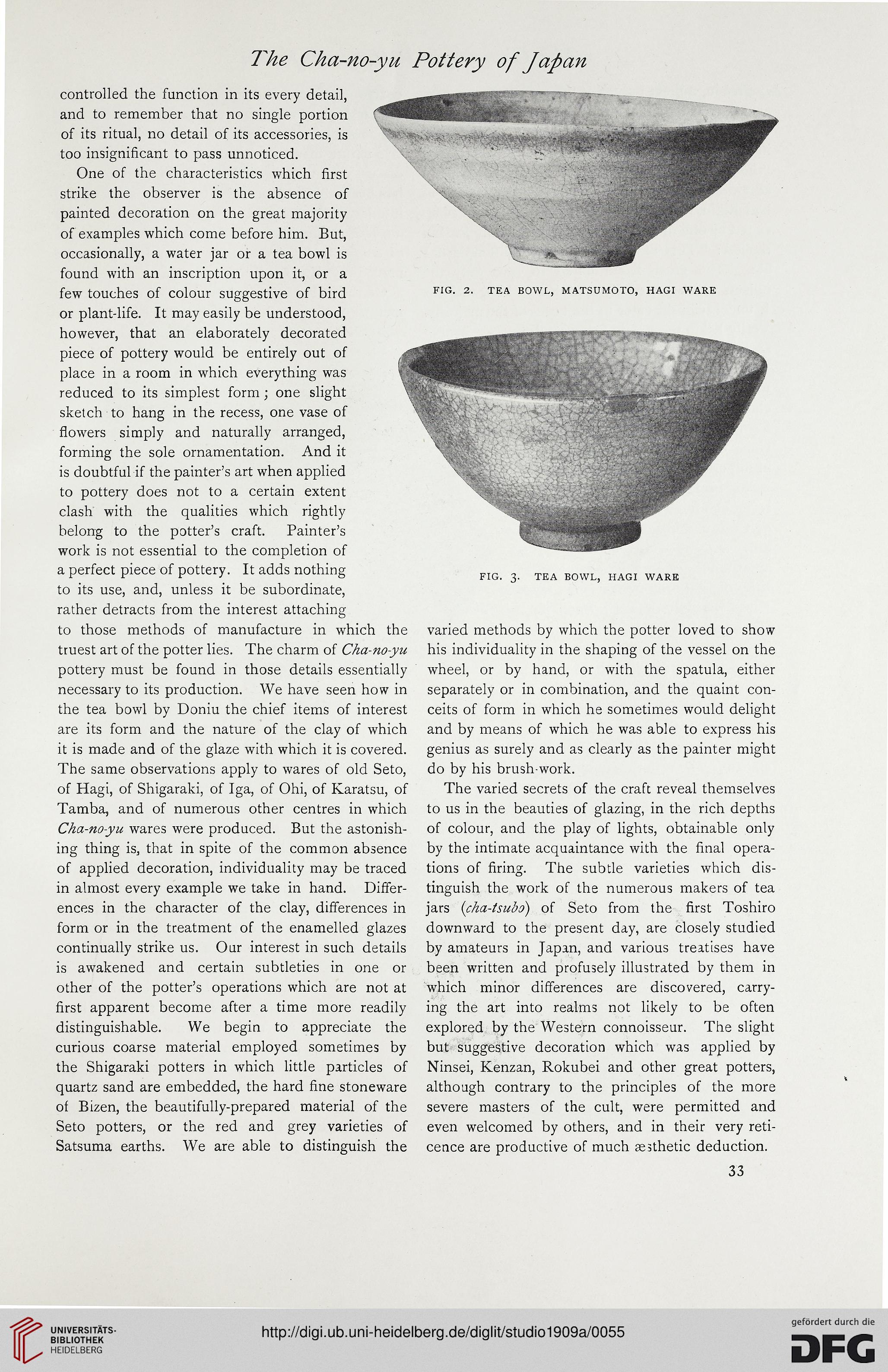

FIG. 3. TEA BOWL, HAGI WARE

varied methods by which the potter loved to show

his individuality in the shaping of the vessel on the

wheel, or by hand, or with the spatula, either

separately or in combination, and the quaint con-

ceits of form in which he sometimes would delight

and by means of which he was able to express his

genius as surely and as clearly as the painter might

do by his brush-work.

The varied secrets of the craft reveal themselves

to us in the beauties of glazing, in the rich depths

of colour, and the play of lights, obtainable only

by the intimate acquaintance with the final opera-

tions of firing. The subtle varieties which dis-

tinguish the work of the numerous makers of tea

jars (cha-tsubo) of Seto from the first Toshiro

downward to the present day, are closely studied

by amateurs in Japan, and various treatises have

been written and profusely illustrated by them in

which minor differences are discovered, carry-

ing the art into realms not likely to be often

explored by the Western connoisseur. The slight

but suggestive decoration which was applied by

Ninsei, Kenzan, Rokubei and other great potters,

although contrary to the principles of the more

severe masters of the cult, were permitted and

even welcomed by others, and in their very reti-

cence are productive of much aesthetic deduction.

33

controlled the function in its every detail,

and to remember that no single portion

of its ritual, no detail of its accessories, is

too insignificant to pass unnoticed.

One of the characteristics which first

strike the observer is the absence of

painted decoration on the great majority

of examples which come before him. But,

occasionally, a water jar or a tea bowl is

found with an inscription upon it, or a

few touches of colour suggestive of bird

or plant-life. It may easily be understood,

however, that an elaborately decorated

piece of pottery would be entirely out of

place in a room in which everything was

reduced to its simplest form; one slight

sketch to hang in the recess, one vase of

flowers simply and naturally arranged,

forming the sole ornamentation. And it

is doubtful if the painter’s art when applied

to pottery does not to a certain extent

clash with the qualities which rightly

belong to the potter’s craft. Painter’s

work is not essential to the completion of

a perfect piece of pottery. It adds nothing

to its use, and, unless it be subordinate,

rather detracts from the interest attaching

to those methods of manufacture in which the

truest art of the potter lies. The charm of Cha-no-yu

pottery must be found in those details essentially

necessary to its production. We have seen how in

the tea bowl by Doniu the chief items of interest

are its form and the nature of the clay of which

it is made and of the glaze with which it is covered.

The same observations apply to wares of old Seto,

of Hagi, of Shigaraki, of Iga, of Ohi, of Karatsu, of

Tamba, and of numerous other centres in which

Cha-no-yu wares were produced. But the astonish-

ing thing is, that in spite of the common absence

of applied decoration, individuality may be traced

in almost every example we take in hand. Differ-

ences in the character of the clay, differences in

form or in the treatment of the enamelled glazes

continually strike us. Our interest in such details

is awakened and certain subtleties in one or

other of the potter’s operations which are not at

first apparent become after a time more readily

distinguishable. We begin to appreciate the

curious coarse material employed sometimes by

the Shigaraki potters in which little particles of

quartz sand are embedded, the hard fine stoneware

of Bizen, the beautifully-prepared material of the

Seto potters, or the red and grey varieties of

Satsuma earths. We are able to distinguish the

FIG. 2. TEA BOWL, MATSUMOTO, HAGI WARE

FIG. 3. TEA BOWL, HAGI WARE

varied methods by which the potter loved to show

his individuality in the shaping of the vessel on the

wheel, or by hand, or with the spatula, either

separately or in combination, and the quaint con-

ceits of form in which he sometimes would delight

and by means of which he was able to express his

genius as surely and as clearly as the painter might

do by his brush-work.

The varied secrets of the craft reveal themselves

to us in the beauties of glazing, in the rich depths

of colour, and the play of lights, obtainable only

by the intimate acquaintance with the final opera-

tions of firing. The subtle varieties which dis-

tinguish the work of the numerous makers of tea

jars (cha-tsubo) of Seto from the first Toshiro

downward to the present day, are closely studied

by amateurs in Japan, and various treatises have

been written and profusely illustrated by them in

which minor differences are discovered, carry-

ing the art into realms not likely to be often

explored by the Western connoisseur. The slight

but suggestive decoration which was applied by

Ninsei, Kenzan, Rokubei and other great potters,

although contrary to the principles of the more

severe masters of the cult, were permitted and

even welcomed by others, and in their very reti-

cence are productive of much aesthetic deduction.

33