Three Painters of the New York School

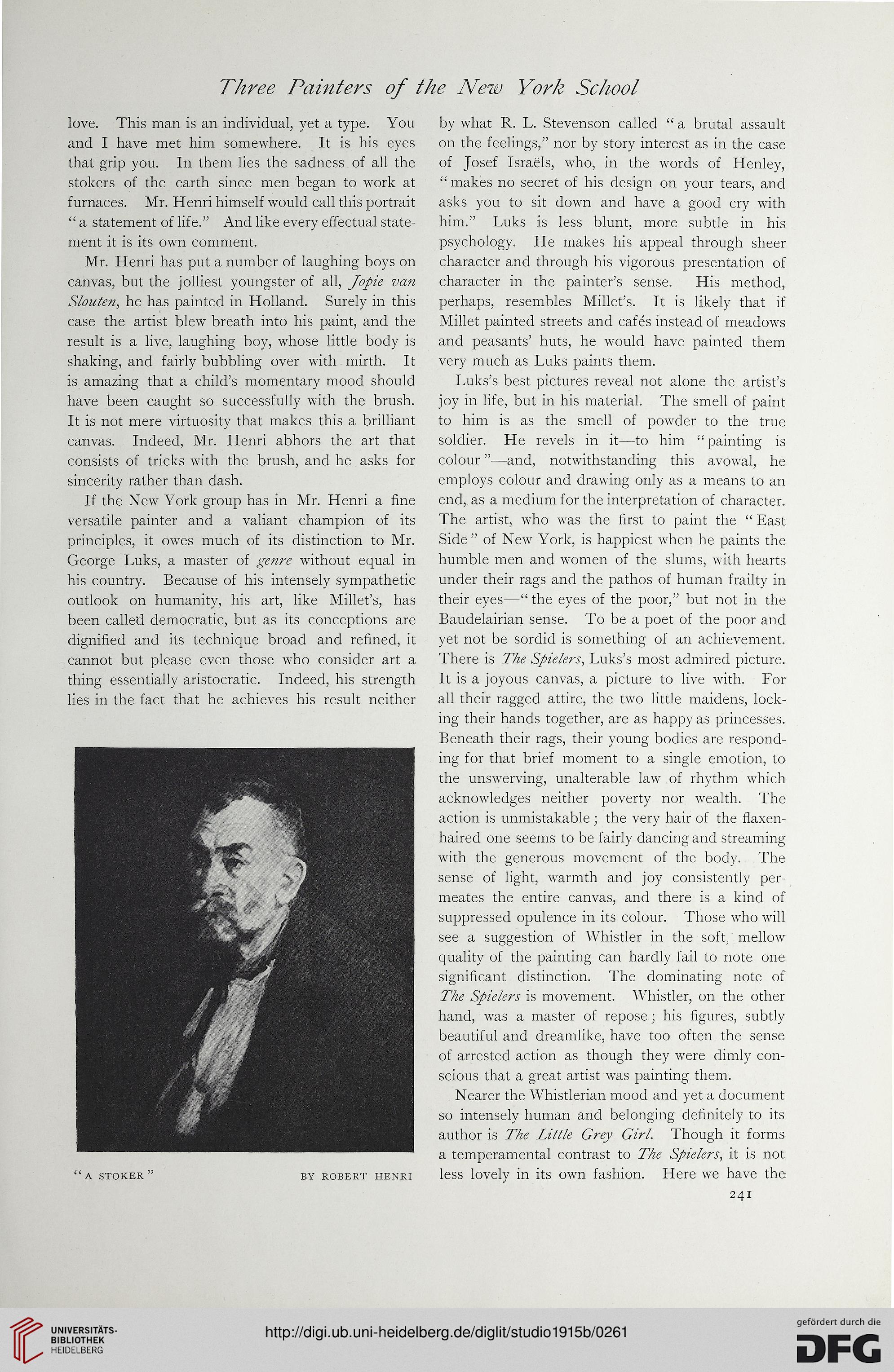

love. This man is an individual, yet a type. You

and I have met him somewhere. It is his eyes

that grip you. In them lies the sadness of all the

stokers of the earth since men began to work at

furnaces. Mr. Henri himself would call this portrait

“ a statement of life.” And like every effectual state-

ment it is its own comment.

Mr. Henri has put a number of laughing boys on

canvas, but the jolliest youngster of all, Jopie van

Slouten, he has painted in Holland. Surely in this

case the artist blew breath into his paint, and the

result is a live, laughing boy, whose little body is

shaking, and fairly bubbling over with mirth. It

is amazing that a child’s momentary mood should

have been caught so successfully with the brush.

It is not mere virtuosity that makes this a brilliant

canvas. Indeed, Mr. Henri abhors the art that

consists of tricks with the brush, and he asks for

sincerity rather than dash.

If the New York group has in Mr. Henri a fine

versatile painter and a valiant champion of its

principles, it owes much of its distinction to Mr.

George Luks, a master of genre without equal in

his country. Because of his intensely sympathetic

outlook on humanity, his art, like Millet’s, has

been called democratic, but as its conceptions are

dignified and its technique broad and refined, it

cannot but please even those who consider art a

thing essentially aristocratic. Indeed, his strength

lies in the fact that he achieves his result neither

by what R. L. Stevenson called “ a brutal assault

on the feelings,” nor by story interest as in the case

of Josef Israels, who, in the words of Henley,

“ makes no secret of his design on your tears, and

asks you to sit down and have a good cry with

him.” Luks is less blunt, more subtle in his

psychology. He makes his appeal through sheer

character and through his vigorous presentation of

character in the painter’s sense. His method,

perhaps, resembles Millet’s. It is likely that if

Millet painted streets and cafes instead of meadows

and peasants’ huts, he would have painted them

very much as Luks paints them.

Luks’s best pictures reveal not alone the artist’s

joy in life, but in his material. The smell of paint

to him is as the smell of powder to the true

soldier. He revels in it—to him “painting is

colour ”—and, notwithstanding this avowal, he

employs colour and drawing only as a means to an

end,, as a medium for the interpretation of character.

The artist, who was the first to paint the “ East

Side” of New York, is happiest when he paints the

humble men and women of the slums, with hearts

under their rags and the pathos of human frailty in

their eyes—“ the eyes of the poor,” but not in the

Baudelairian sense. To be a poet of the poor and

yet not be sordid is something of an achievement.

There is The Spielers, Luks’s most admired picture.

It is a joyous canvas, a picture to live with. For

all their ragged attire, the two little maidens, lock-

ing their hands together, are as happy as princesses.

Beneath their rags, their young bodies are respond-

ing for that brief moment to a single emotion, to

the unswerving, unalterable law of rhythm which

acknowledges neither poverty nor wealth. The

action is unmistakable ; the very hair of the flaxen-

haired one seems to be fairly dancing and streaming

with the generous movement of the body. The

sense of light, warmth and joy consistently per-

meates the entire canvas, and there is a kind of

suppressed opulence in its colour. Those who will

see a suggestion of Whistler in the soft, mellow

quality of the painting can hardly fail to note one

significant distinction. The dominating note of

The Spielers is movement. Whistler, on the other

hand, was a master of repose; his figures, subtly

beautiful and dreamlike, have too often the sense

of arrested action as though they were dimly con-

scious that a great artist was painting them.

Nearer the Whistlerian mood and yet a document

so intensely human and belonging definitely to its

author is The Little Grey Girl. Though it forms

a temperamental contrast to The Spielers, it is not

less lovely in its own fashion. Here we have the

241

“a stoker ”

BY ROBERT HENRI

love. This man is an individual, yet a type. You

and I have met him somewhere. It is his eyes

that grip you. In them lies the sadness of all the

stokers of the earth since men began to work at

furnaces. Mr. Henri himself would call this portrait

“ a statement of life.” And like every effectual state-

ment it is its own comment.

Mr. Henri has put a number of laughing boys on

canvas, but the jolliest youngster of all, Jopie van

Slouten, he has painted in Holland. Surely in this

case the artist blew breath into his paint, and the

result is a live, laughing boy, whose little body is

shaking, and fairly bubbling over with mirth. It

is amazing that a child’s momentary mood should

have been caught so successfully with the brush.

It is not mere virtuosity that makes this a brilliant

canvas. Indeed, Mr. Henri abhors the art that

consists of tricks with the brush, and he asks for

sincerity rather than dash.

If the New York group has in Mr. Henri a fine

versatile painter and a valiant champion of its

principles, it owes much of its distinction to Mr.

George Luks, a master of genre without equal in

his country. Because of his intensely sympathetic

outlook on humanity, his art, like Millet’s, has

been called democratic, but as its conceptions are

dignified and its technique broad and refined, it

cannot but please even those who consider art a

thing essentially aristocratic. Indeed, his strength

lies in the fact that he achieves his result neither

by what R. L. Stevenson called “ a brutal assault

on the feelings,” nor by story interest as in the case

of Josef Israels, who, in the words of Henley,

“ makes no secret of his design on your tears, and

asks you to sit down and have a good cry with

him.” Luks is less blunt, more subtle in his

psychology. He makes his appeal through sheer

character and through his vigorous presentation of

character in the painter’s sense. His method,

perhaps, resembles Millet’s. It is likely that if

Millet painted streets and cafes instead of meadows

and peasants’ huts, he would have painted them

very much as Luks paints them.

Luks’s best pictures reveal not alone the artist’s

joy in life, but in his material. The smell of paint

to him is as the smell of powder to the true

soldier. He revels in it—to him “painting is

colour ”—and, notwithstanding this avowal, he

employs colour and drawing only as a means to an

end,, as a medium for the interpretation of character.

The artist, who was the first to paint the “ East

Side” of New York, is happiest when he paints the

humble men and women of the slums, with hearts

under their rags and the pathos of human frailty in

their eyes—“ the eyes of the poor,” but not in the

Baudelairian sense. To be a poet of the poor and

yet not be sordid is something of an achievement.

There is The Spielers, Luks’s most admired picture.

It is a joyous canvas, a picture to live with. For

all their ragged attire, the two little maidens, lock-

ing their hands together, are as happy as princesses.

Beneath their rags, their young bodies are respond-

ing for that brief moment to a single emotion, to

the unswerving, unalterable law of rhythm which

acknowledges neither poverty nor wealth. The

action is unmistakable ; the very hair of the flaxen-

haired one seems to be fairly dancing and streaming

with the generous movement of the body. The

sense of light, warmth and joy consistently per-

meates the entire canvas, and there is a kind of

suppressed opulence in its colour. Those who will

see a suggestion of Whistler in the soft, mellow

quality of the painting can hardly fail to note one

significant distinction. The dominating note of

The Spielers is movement. Whistler, on the other

hand, was a master of repose; his figures, subtly

beautiful and dreamlike, have too often the sense

of arrested action as though they were dimly con-

scious that a great artist was painting them.

Nearer the Whistlerian mood and yet a document

so intensely human and belonging definitely to its

author is The Little Grey Girl. Though it forms

a temperamental contrast to The Spielers, it is not

less lovely in its own fashion. Here we have the

241

“a stoker ”

BY ROBERT HENRI