PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

S

private and confidential.

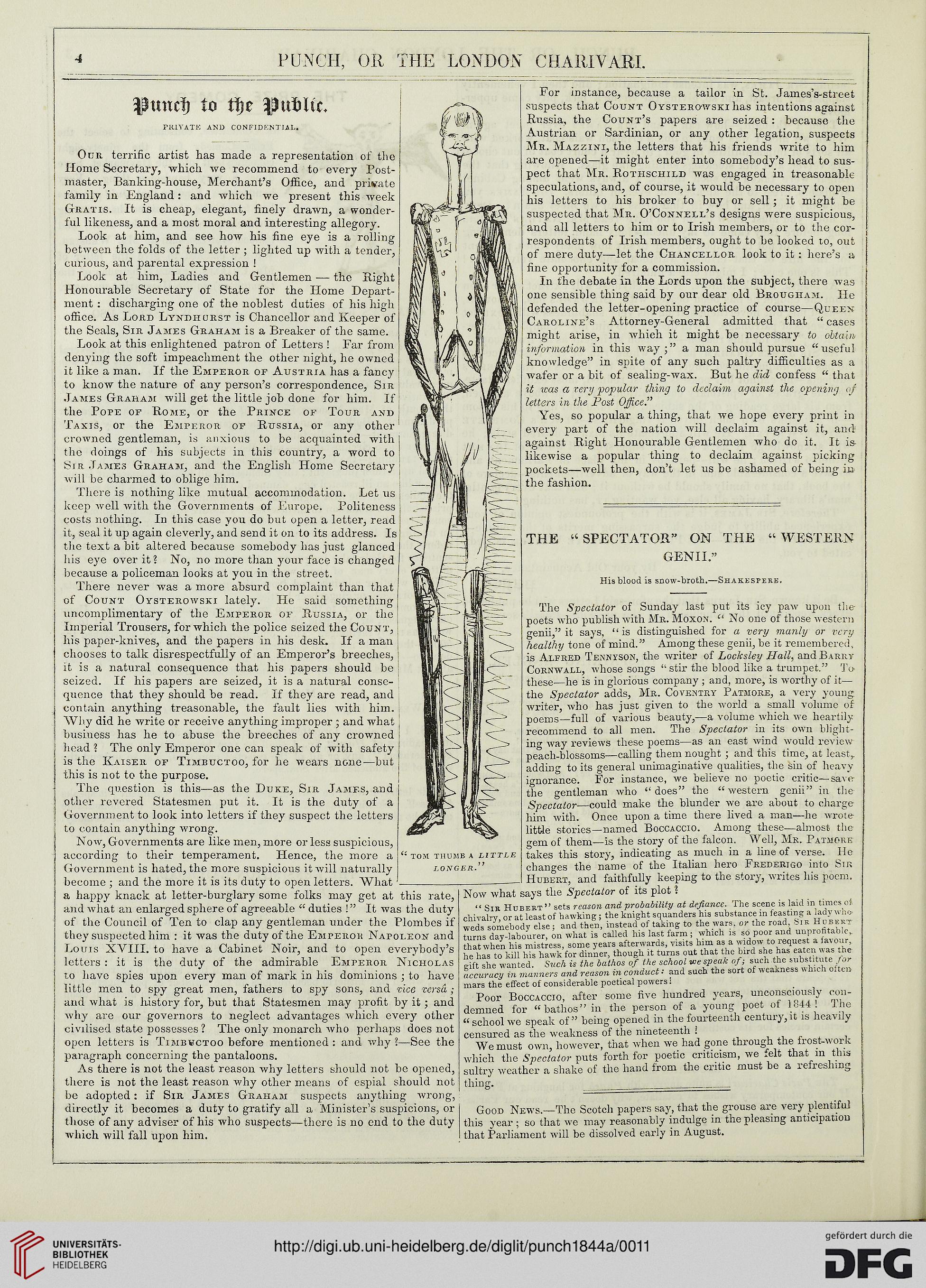

Our terrific artist has made a representation of the

Home Secretary, which we recommend to every Post-

master, Banking-house, Merchant's Office, and private

family in England : and which we present this week

Gratis. It is cheap, elegant, finely drawn, a wonder-

ful likeness, and a most moral and interesting allegory.

Look at him, and see how his fine eye is a rolling

between the folds of the letter ; lighted up with a tender,

curious, and parental expression !

Look at him, Ladies and Gentlemen — the Right

Honourable Secretary of State for the Home Depart-

ment : discharging one of the noblest duties of his high

office. As Lord Lynbhorst is Chancellor and Keeper of

the Seals, Sir James Graham is a Breaker of the same.

Look at this enlightened patron of Letters ! Far from

denying the soft impeachment the other night, he owned

it like a man. If the Emperor of Austria has a fancy

to know the nature of any person's correspondence, Sir

James Graham will get the little job done for him. If

the Pope of Rome, or the Prince of Tour and

Taxis, or the Emperor of Russia, or any other

crowned gentleman, is anxious to be acquainted with

the doings of his subjects in this country, a word to

Sir James Graham, and the English Home Secretary

will be charmed to oblige him.

There is nothing like mutual accommodation. Let us

keep well with the Governments of Europe. Politeness

costs nothing. In this case you do but open a letter, read

it, seal it up again cleverly, and send it on to its address. Is

the text a bit altered because somebody has just glanced

his eye over it? No, no more than your face is changed

because a policeman looks at you in the street.

There never was a more absurd complaint than that

of Count Oysterowski lately. Pie said something

uncomplimentary of the Emperor of Russia, or the

Imperial Trousers, for which the police seized the Count,

his paper-knives, and the papers in his desk. If a man

chooses to talk disrespectfully of an Emperor's breeches,

it is a natural consequence that his papers should be

seized. If his papers are seized, it is a natural conse-

quence that they should be read. If they are read, and

contain anything treasonable, the fault lies with him.

Why did he write or receive anything improper ; and what

business has he to abuse the breeches of any crowned

head ? The only Emperor one can speak of with safety

is the Kaiser of Timbuctoo, for he wears none—but

this is not to the purpose.

The question is this—as the Duke, Sir James, and

other revered Statesmen put it. It is the duty of a

Government to look into letters if they suspect the letters

to contain anything wrong.

Now, Governments are like men, more or less suspicious,

according to their temperament. Hence, the more a

Government is hated, the more suspicious it will naturally

become ; and the more it is its duty to open letters. What

a happy knack at letter-burglary some folks may get at this rate,

and what an enlarged sphere of agreeable " duties !" It was the duty

of the Council of Ten to clap any gentleman under the Plombcs if

they suspected him : it was the duty of the Emperor Napoleon and

Louis XVIII. to have a Cabinet Noir, and to open everybody's

letters : it is the duty of the admirable Emperor Nicholas

to have spies upon every man of mark in his dominions ; to have

little men to spy great men, fathers to spy sons, and rice versa;

and what is history for, but that Statesmen may profit by it; and

why are our governors to neglect advantages which every other

civilised state possesses 1 The only monarch who perhaps does not

open letters is Timbvctoo before mentioned : and why ?—See the

paragraph concerning the pantaloons.

As there is not the least reason why letters should not be opened,

there is not the least reason why other means of espial should not

be adopted: if Sir James Graham suspects anything wrong,

directly it becomes a duty to gratify all a Minister's suspicions, or

those of any adviser of his who suspects—there is no end to the duty

which will fall upon him.

v.

tom thumb a

LONGER

For instance, because a tailor in St. James's-street

suspects that Count Oysterowski has intentions against

Russia, the Count's papers are seized : because the

Austrian or Sardinian, or any other legation, suspects

Mr. Mazzini, the letters that his friends write to him

are opened—it might enter into somebody's head to sus-

pect that Mr. Rothschild was engaged in treasonable

speculations, and, of course, it would be necessary to open

his letters to his broker to buy or sell; it might be

suspected that Mr. O'Connell's designs were suspicious,

and all letters to him or to Irish members, or to the cor-

respondents of Irish members, ought to be looked to, out

of mere duty—let the Chancellor look to it : here's a

fine opportunity for a commission.

In the debate in the Lords upon the subject, there was

one sensible thing said by our dear old Brougham. He

defended the letter-opening practice of course—Queen

Caroline's Attorney-General admitted that " cases

might arise, in which it might be necessary to obtain

information in this way;" a man should pursue "useful

knowledge" in spite of any such paltry difficulties as a

wafer or a bit of sealing-wax. But he did confess " that

it icas a very popular thing to declaim against the opening of

letters in the Post Office."

Yes, so popular a thing, that we hope every print in

every part of the nation will declaim against it, and

against Riffht Honourable Gentlemen who do it. It is-

likewise a popular thing to declaim against picking

pockets—well then, don't let us be ashamed of being m

the fashion.

THE " SPECTATOR" ON THE " WESTERN

GENII."

His blood is snow-broth.—Shakesferk.

The Spectator of Sunday last put its icy paw upon

poets who publish with Mr. Moxon. c< No one of those western

genii," it says, "is distinguished for a very manly or very

healthy tone of mind." Among these genii, be it remembered,

is Alfred Tennyson, the writer of Locksley Hall, and Barry

Cornwall, whose songs "stir the blood like a trumpet." To

these—he is in glorious company ; and, more, is worthy of it—

the Spectator adds, Mr. Coventry Patmore, a very young

writer, who has jusc given to the world a small volume of

poems—full of various beauty,—a volume which we heartily

recommend to all men. The Spectator in its own blight-

ing way reviews these poems—as an east wind would review

peach-blossoms—calling them nought ; and this time, at leasts

adding to its general unimaginative qualities, the sin of heavy-

ignorance. For instance, we believe no poetic critic— save

the gentleman who " does" the " western genii" in the

Spectator—could make the blunder we are about to charge

him with. Once upon a time there lived a man—lie wrote

little stories—named Boccaccio. Among these—almost the

gem of them—is the story of the falcon. Well, Mr. Pat.mork

takes this story, indicating as much in a line of verse. He

changes the name of the Italian hero Frederigo into Sir

Hubert, and faithfully keeping to the story, writes his poem.

Now what says the Spectator of its plot ?

" Sib Hubert" sets reason and probability at defiance. The scene is laid in times of

chivalry, or at least of hawking; the knight squanders his substance in feasting a l?dywhc

weds somebody else ; and then, instead of taking to the wars, or the road Sir H u e n

turns day-labourer, on what is called his last farm; which is so poor and unprofitable,

hat when his mist ess, some years afterwards, visits him as a widow to request a favour,

be l as to"k1his hawk for dinner, though it turns out that the bird she has eaten was the

cif she wanted. Such is the bathos of the school we speak of; such the substitute for

Tccuracy in manners and reason in conduct: and such the sort of weakness which often

mars the effect of considerable poetical powers:

Poor Boccaccio, after some five hundred years, unconsciously con-

demned for "bathos" in the person of a young poet of 1844 the

« school we speak of" being opened in the fourteenth century, it is heavily

censured as the weakness of the nineteenth ! , — . ,

We must own, however, that when we had gone through the: frost-work

which the Spectator puts forth for poetic criticism, we felt that m this

sultry weather a shake of the hand from the critic must be a refreshing

thing. _ _ ___

Good News.—The Scotch papers say, that the grouse are very plentiful

this year ; so that we may reasonably indulge in the pleasing anticipation

that Parliament will be dissolved early in August.

S

private and confidential.

Our terrific artist has made a representation of the

Home Secretary, which we recommend to every Post-

master, Banking-house, Merchant's Office, and private

family in England : and which we present this week

Gratis. It is cheap, elegant, finely drawn, a wonder-

ful likeness, and a most moral and interesting allegory.

Look at him, and see how his fine eye is a rolling

between the folds of the letter ; lighted up with a tender,

curious, and parental expression !

Look at him, Ladies and Gentlemen — the Right

Honourable Secretary of State for the Home Depart-

ment : discharging one of the noblest duties of his high

office. As Lord Lynbhorst is Chancellor and Keeper of

the Seals, Sir James Graham is a Breaker of the same.

Look at this enlightened patron of Letters ! Far from

denying the soft impeachment the other night, he owned

it like a man. If the Emperor of Austria has a fancy

to know the nature of any person's correspondence, Sir

James Graham will get the little job done for him. If

the Pope of Rome, or the Prince of Tour and

Taxis, or the Emperor of Russia, or any other

crowned gentleman, is anxious to be acquainted with

the doings of his subjects in this country, a word to

Sir James Graham, and the English Home Secretary

will be charmed to oblige him.

There is nothing like mutual accommodation. Let us

keep well with the Governments of Europe. Politeness

costs nothing. In this case you do but open a letter, read

it, seal it up again cleverly, and send it on to its address. Is

the text a bit altered because somebody has just glanced

his eye over it? No, no more than your face is changed

because a policeman looks at you in the street.

There never was a more absurd complaint than that

of Count Oysterowski lately. Pie said something

uncomplimentary of the Emperor of Russia, or the

Imperial Trousers, for which the police seized the Count,

his paper-knives, and the papers in his desk. If a man

chooses to talk disrespectfully of an Emperor's breeches,

it is a natural consequence that his papers should be

seized. If his papers are seized, it is a natural conse-

quence that they should be read. If they are read, and

contain anything treasonable, the fault lies with him.

Why did he write or receive anything improper ; and what

business has he to abuse the breeches of any crowned

head ? The only Emperor one can speak of with safety

is the Kaiser of Timbuctoo, for he wears none—but

this is not to the purpose.

The question is this—as the Duke, Sir James, and

other revered Statesmen put it. It is the duty of a

Government to look into letters if they suspect the letters

to contain anything wrong.

Now, Governments are like men, more or less suspicious,

according to their temperament. Hence, the more a

Government is hated, the more suspicious it will naturally

become ; and the more it is its duty to open letters. What

a happy knack at letter-burglary some folks may get at this rate,

and what an enlarged sphere of agreeable " duties !" It was the duty

of the Council of Ten to clap any gentleman under the Plombcs if

they suspected him : it was the duty of the Emperor Napoleon and

Louis XVIII. to have a Cabinet Noir, and to open everybody's

letters : it is the duty of the admirable Emperor Nicholas

to have spies upon every man of mark in his dominions ; to have

little men to spy great men, fathers to spy sons, and rice versa;

and what is history for, but that Statesmen may profit by it; and

why are our governors to neglect advantages which every other

civilised state possesses 1 The only monarch who perhaps does not

open letters is Timbvctoo before mentioned : and why ?—See the

paragraph concerning the pantaloons.

As there is not the least reason why letters should not be opened,

there is not the least reason why other means of espial should not

be adopted: if Sir James Graham suspects anything wrong,

directly it becomes a duty to gratify all a Minister's suspicions, or

those of any adviser of his who suspects—there is no end to the duty

which will fall upon him.

v.

tom thumb a

LONGER

For instance, because a tailor in St. James's-street

suspects that Count Oysterowski has intentions against

Russia, the Count's papers are seized : because the

Austrian or Sardinian, or any other legation, suspects

Mr. Mazzini, the letters that his friends write to him

are opened—it might enter into somebody's head to sus-

pect that Mr. Rothschild was engaged in treasonable

speculations, and, of course, it would be necessary to open

his letters to his broker to buy or sell; it might be

suspected that Mr. O'Connell's designs were suspicious,

and all letters to him or to Irish members, or to the cor-

respondents of Irish members, ought to be looked to, out

of mere duty—let the Chancellor look to it : here's a

fine opportunity for a commission.

In the debate in the Lords upon the subject, there was

one sensible thing said by our dear old Brougham. He

defended the letter-opening practice of course—Queen

Caroline's Attorney-General admitted that " cases

might arise, in which it might be necessary to obtain

information in this way;" a man should pursue "useful

knowledge" in spite of any such paltry difficulties as a

wafer or a bit of sealing-wax. But he did confess " that

it icas a very popular thing to declaim against the opening of

letters in the Post Office."

Yes, so popular a thing, that we hope every print in

every part of the nation will declaim against it, and

against Riffht Honourable Gentlemen who do it. It is-

likewise a popular thing to declaim against picking

pockets—well then, don't let us be ashamed of being m

the fashion.

THE " SPECTATOR" ON THE " WESTERN

GENII."

His blood is snow-broth.—Shakesferk.

The Spectator of Sunday last put its icy paw upon

poets who publish with Mr. Moxon. c< No one of those western

genii," it says, "is distinguished for a very manly or very

healthy tone of mind." Among these genii, be it remembered,

is Alfred Tennyson, the writer of Locksley Hall, and Barry

Cornwall, whose songs "stir the blood like a trumpet." To

these—he is in glorious company ; and, more, is worthy of it—

the Spectator adds, Mr. Coventry Patmore, a very young

writer, who has jusc given to the world a small volume of

poems—full of various beauty,—a volume which we heartily

recommend to all men. The Spectator in its own blight-

ing way reviews these poems—as an east wind would review

peach-blossoms—calling them nought ; and this time, at leasts

adding to its general unimaginative qualities, the sin of heavy-

ignorance. For instance, we believe no poetic critic— save

the gentleman who " does" the " western genii" in the

Spectator—could make the blunder we are about to charge

him with. Once upon a time there lived a man—lie wrote

little stories—named Boccaccio. Among these—almost the

gem of them—is the story of the falcon. Well, Mr. Pat.mork

takes this story, indicating as much in a line of verse. He

changes the name of the Italian hero Frederigo into Sir

Hubert, and faithfully keeping to the story, writes his poem.

Now what says the Spectator of its plot ?

" Sib Hubert" sets reason and probability at defiance. The scene is laid in times of

chivalry, or at least of hawking; the knight squanders his substance in feasting a l?dywhc

weds somebody else ; and then, instead of taking to the wars, or the road Sir H u e n

turns day-labourer, on what is called his last farm; which is so poor and unprofitable,

hat when his mist ess, some years afterwards, visits him as a widow to request a favour,

be l as to"k1his hawk for dinner, though it turns out that the bird she has eaten was the

cif she wanted. Such is the bathos of the school we speak of; such the substitute for

Tccuracy in manners and reason in conduct: and such the sort of weakness which often

mars the effect of considerable poetical powers:

Poor Boccaccio, after some five hundred years, unconsciously con-

demned for "bathos" in the person of a young poet of 1844 the

« school we speak of" being opened in the fourteenth century, it is heavily

censured as the weakness of the nineteenth ! , — . ,

We must own, however, that when we had gone through the: frost-work

which the Spectator puts forth for poetic criticism, we felt that m this

sultry weather a shake of the hand from the critic must be a refreshing

thing. _ _ ___

Good News.—The Scotch papers say, that the grouse are very plentiful

this year ; so that we may reasonably indulge in the pleasing anticipation

that Parliament will be dissolved early in August.

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

"Tom Thumb a little longer."

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Entstehungsdatum

um 1844

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1839 - 1849

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 7.1844, July to December, 1844, S. 4

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg