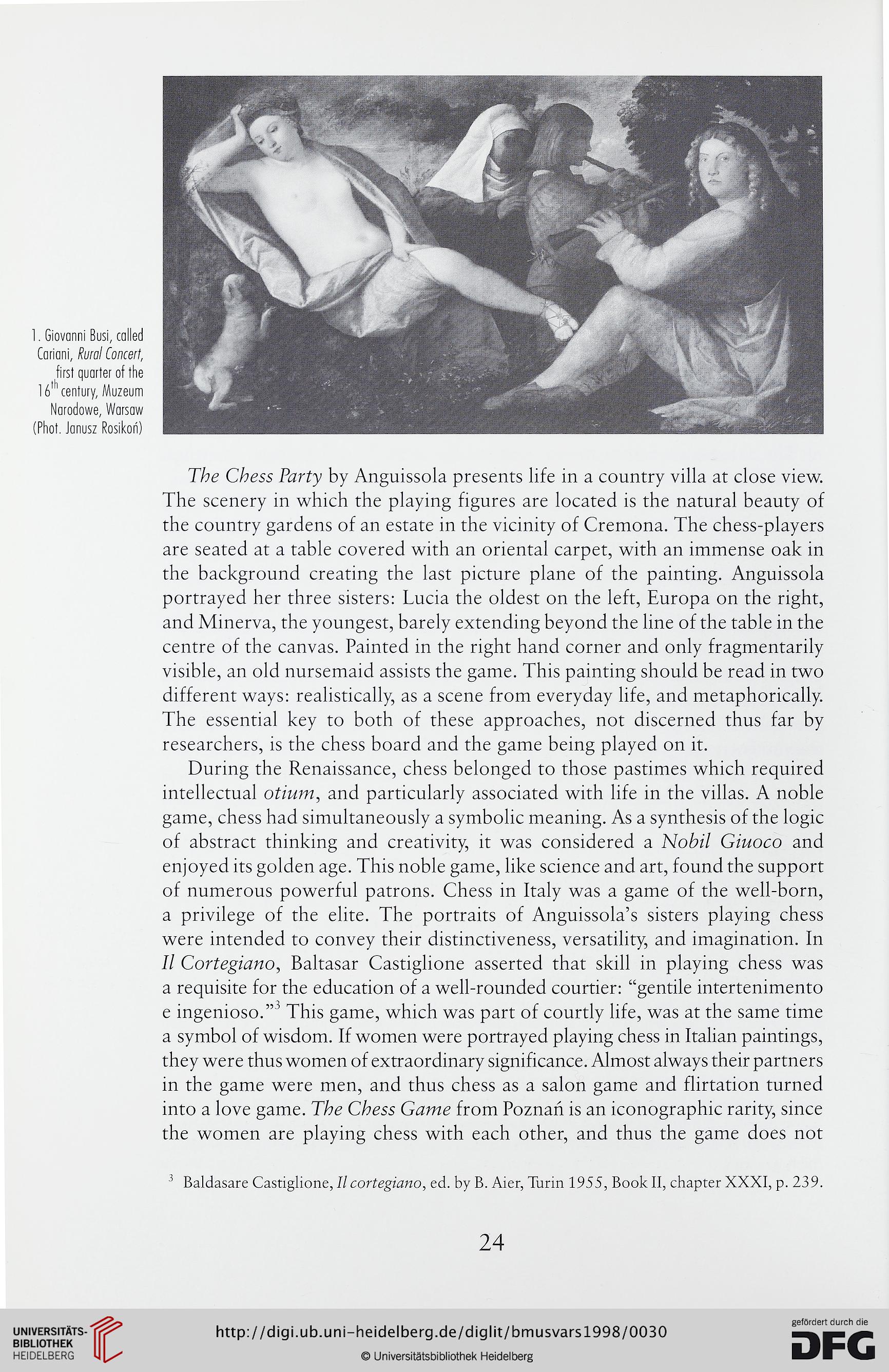

1. Giovanni Busi, called

Cariani, Rurol Concert,

first quarter of the

16lh century. Muzeum

Narodowe, Warsaw

(Phoł. Janusz Rosikoń)

The Chess Party by Anguissola presents life in a country villa at close view.

The scenery in which the playing figures are located is the natural beauty of

the country gardens of an estate in the vicinity of Cremona. The chess-players

are seated at a table covered with an oriental carpet, with an immense oak in

the background creating the last picture piane of the painting. Anguissola

portrayed her three sisters: Tucia the oldest on the left, Europa on the right,

and Minerva, the youngest, barely extending beyond the linę of the table in the

centre of the canvas. Painted in the right hand corner and only fragmentarily

visible, an old nursemaid assists the gamę. This painting should be read in two

different ways: realistically, as a scene from everyday life, and metaphorically.

The essential key to both of these approaches, not discerned thus far by

researchers, is the chess board and the gamę being played on it.

During the Renaissance, chess belonged to those pastimes which reąuired

intellectual otium, and particularly associated with life in the villas. A noble

gamę, chess had simultaneously a symbolic meaning. As a synthesis of the logie

of abstract thinking and creativity, it was considered a Nobil Giuoco and

enjoyed its golden age. This noble gamę, like science and art, found the support

of numerous powerful patrons. Chess in Italy was a gamę of the well-born,

a priyilege of the elite. The portraits of Anguissola’s sisters playmg chess

were intended to convey their distinctiveness, versatility, and imagination. In

II Cortegiano, Baltasar Castiglione asserted that skill in playing chess was

a reąuisite for the education of a well-rounded courtier: “gentile intertenimento

e ingenioso.”’ This gamę, which was part of courtly life, was at the same time

a symbol of wisdom. If women were portrayed playing chess in Italian paintings,

they were thus women of extraordinary significance. Almost always their partners

in the gamę were men, and thus chess as a salon gamę and flirtation turned

into a love gamę. The Chess Gamę from Poznań is an iconographic rarity, sińce

the women are playing chess with each other, and thus the gamę does not

’ Baldasare Castiglione, II cortegiano, ed. by B. Aier, Turin 1955, Book II, chapter XXXI, p. 239.

24

Cariani, Rurol Concert,

first quarter of the

16lh century. Muzeum

Narodowe, Warsaw

(Phoł. Janusz Rosikoń)

The Chess Party by Anguissola presents life in a country villa at close view.

The scenery in which the playing figures are located is the natural beauty of

the country gardens of an estate in the vicinity of Cremona. The chess-players

are seated at a table covered with an oriental carpet, with an immense oak in

the background creating the last picture piane of the painting. Anguissola

portrayed her three sisters: Tucia the oldest on the left, Europa on the right,

and Minerva, the youngest, barely extending beyond the linę of the table in the

centre of the canvas. Painted in the right hand corner and only fragmentarily

visible, an old nursemaid assists the gamę. This painting should be read in two

different ways: realistically, as a scene from everyday life, and metaphorically.

The essential key to both of these approaches, not discerned thus far by

researchers, is the chess board and the gamę being played on it.

During the Renaissance, chess belonged to those pastimes which reąuired

intellectual otium, and particularly associated with life in the villas. A noble

gamę, chess had simultaneously a symbolic meaning. As a synthesis of the logie

of abstract thinking and creativity, it was considered a Nobil Giuoco and

enjoyed its golden age. This noble gamę, like science and art, found the support

of numerous powerful patrons. Chess in Italy was a gamę of the well-born,

a priyilege of the elite. The portraits of Anguissola’s sisters playmg chess

were intended to convey their distinctiveness, versatility, and imagination. In

II Cortegiano, Baltasar Castiglione asserted that skill in playing chess was

a reąuisite for the education of a well-rounded courtier: “gentile intertenimento

e ingenioso.”’ This gamę, which was part of courtly life, was at the same time

a symbol of wisdom. If women were portrayed playing chess in Italian paintings,

they were thus women of extraordinary significance. Almost always their partners

in the gamę were men, and thus chess as a salon gamę and flirtation turned

into a love gamę. The Chess Gamę from Poznań is an iconographic rarity, sińce

the women are playing chess with each other, and thus the gamę does not

’ Baldasare Castiglione, II cortegiano, ed. by B. Aier, Turin 1955, Book II, chapter XXXI, p. 239.

24