Charles Reid's Animal Photographs

taken the portrait. The travelling photographer’s

charge for one small picture was fifteen shillings.

“It was in 1864,” says Mr. Reid, “that I first

found myself the owner of a small camera. This

instrument would compare very unfavourably with

the camera of to-day, yet it served its purpose at the

time, being used for the production of many portraits

of people who had never before had their features

transferred to glass or paper. Much as photo-

graphs were admired and sought after in the

first blush of their appearance, old-fashioned people

concluded that the thing could not last, that the

custom would inevitably die out as soon as every

person possessed a portrait of himself—even one

glass portrait—and I have good reason to retain a

vivid recollection of the astonishment that prevailed

in the quiet country village where I then lived

consequent on the announcement that I had

actually resolved to build a glass-house to take

portraits in. Some of my acquaintances pitied,

others remonstrated, while a few viewed the under-

taking as an act little short of madness, and

prophesied failure and ruin as the result. Doubt-

less the recollection that there are false as well as

true prophets, coupled with the hope that this

marvellous invention had a great future in store,

impelled me to follow the bent of my inclination

and proceed with the building—a course I never

had reason to regret.”

Portrait photography became Mr. Reid’s business,

but whenever possible he made opportunities for

taking animals of every available breed as a hobby ;

and in course of time gradually amassed a large

and varied collection of animal photographs, which

became known and admired, and led to his being

very frequently commissioned by leading breeders

to take their favourite animals.

Many an interesting experience has fallen to his

and his sons’ lot. Usually, to secure a particular

picture—say of Highland cattle—they journey to

some remote district in the Highlands or Islands of

Scotland, having previously ascertained by personal

investigation or otherwise where the materials for a

picture are to be found. It would be an endless

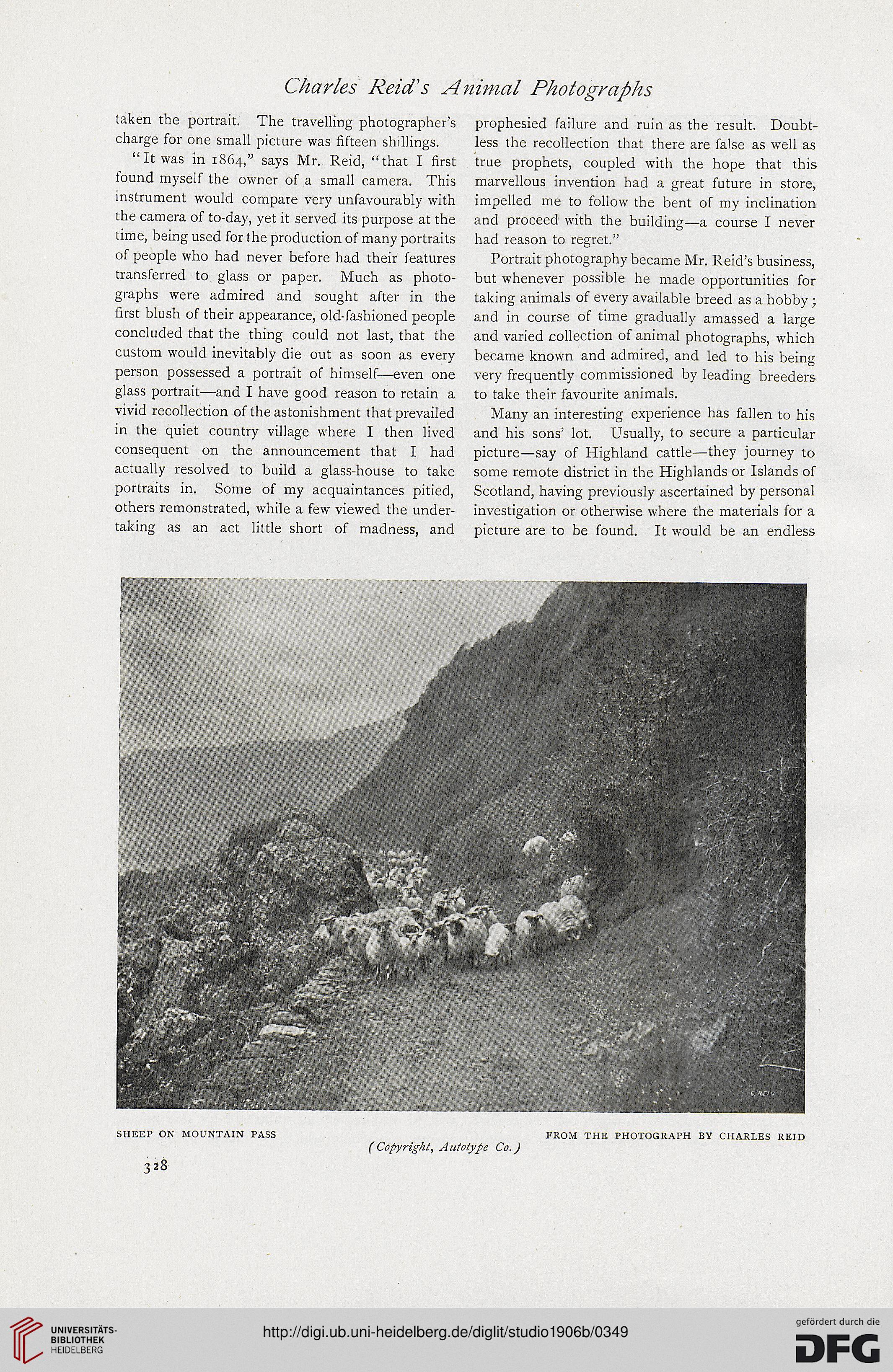

SHEEP ON MOUNTAIN PASS

FROM THE PHOTOGRAPH BY CHARLES REID

328

( Copyright, Autotype Co.)

taken the portrait. The travelling photographer’s

charge for one small picture was fifteen shillings.

“It was in 1864,” says Mr. Reid, “that I first

found myself the owner of a small camera. This

instrument would compare very unfavourably with

the camera of to-day, yet it served its purpose at the

time, being used for the production of many portraits

of people who had never before had their features

transferred to glass or paper. Much as photo-

graphs were admired and sought after in the

first blush of their appearance, old-fashioned people

concluded that the thing could not last, that the

custom would inevitably die out as soon as every

person possessed a portrait of himself—even one

glass portrait—and I have good reason to retain a

vivid recollection of the astonishment that prevailed

in the quiet country village where I then lived

consequent on the announcement that I had

actually resolved to build a glass-house to take

portraits in. Some of my acquaintances pitied,

others remonstrated, while a few viewed the under-

taking as an act little short of madness, and

prophesied failure and ruin as the result. Doubt-

less the recollection that there are false as well as

true prophets, coupled with the hope that this

marvellous invention had a great future in store,

impelled me to follow the bent of my inclination

and proceed with the building—a course I never

had reason to regret.”

Portrait photography became Mr. Reid’s business,

but whenever possible he made opportunities for

taking animals of every available breed as a hobby ;

and in course of time gradually amassed a large

and varied collection of animal photographs, which

became known and admired, and led to his being

very frequently commissioned by leading breeders

to take their favourite animals.

Many an interesting experience has fallen to his

and his sons’ lot. Usually, to secure a particular

picture—say of Highland cattle—they journey to

some remote district in the Highlands or Islands of

Scotland, having previously ascertained by personal

investigation or otherwise where the materials for a

picture are to be found. It would be an endless

SHEEP ON MOUNTAIN PASS

FROM THE PHOTOGRAPH BY CHARLES REID

328

( Copyright, Autotype Co.)