Josef Israels

his own. The tightness which is so apparent in his and thus he would place his melancholy figures in

earlier pictures gradually gave place to a freer a room lit by the dim flame of a candle, or the

handling, until he finally acquired a remarkable tempered light from a window, and he would

looseness of touch which is one of the most pro- clothe them in an atmosphere of grey and sombre

minent characteristics of the work of his maturity, tones. And again, when he depicted children

Here we find no trace of his early academic train- sailing their toy-boat in the sea, the scene would be

ing, no suggestion of the conventional, but a phase bathed in sunlight and the colours would assume a

of an individual technique eminently suited to the lighter and more joyous hue, to suggest the happi-

moods and aims of the artist. The searching ness of childhood. Let us take as an example the

accuracy of drawing and brilliant execution of the picture Honoured Old Age, illustrated on p. 98, with

old Dutch painters, such as Vermeer and Peter de the figure of the old woman warming her hands

Hoogh, did not appeal to him, and Rembrandt is over the fire. The failing light coming through

the only master who appears to have influenced the unseen window, the deepening shadows, the

him. Like his great progenitor, Israels made a stillness of the figure, all suggest the evening of

special study of the treatment of light and shade life, in this case obviously a life of struggle and

in their relation to colour, and in this respect he privation.

had no rival amongst modern painters. Referring In the adaptation of the various elements of his

to this important feature in Israels' art Max Rooses composition one to the other, the blending of light

has said: "He brought about a revolution in painting and shade, the harmonising of colours, the subtle

by reforming the part played by light and colour; graduating of tones, and the avoidance of discordant

these were no longer independent in their strength notes or striking passages likely to interfere with

and brilliancy, but mingled, dissolved, melted into the general unity of the whole, Israels has worthily

a whole, in which all is equal, all is adequate, upheld the finest traditions of his national art.

nothing dominating, nothing yielding." Here we have the true explanation of his affinity

But perhaps the keynote of Israels' success may to the seventeenth-century Dutchmen. In the

be found in the fact that in his pictures subject selection of his principal subjects he showed little

and surroundings are always in harmony. To him in common with them-—for they seldom concerned

every theme should have its own peculiar setting ; themselves with sorrow and mourning, though the

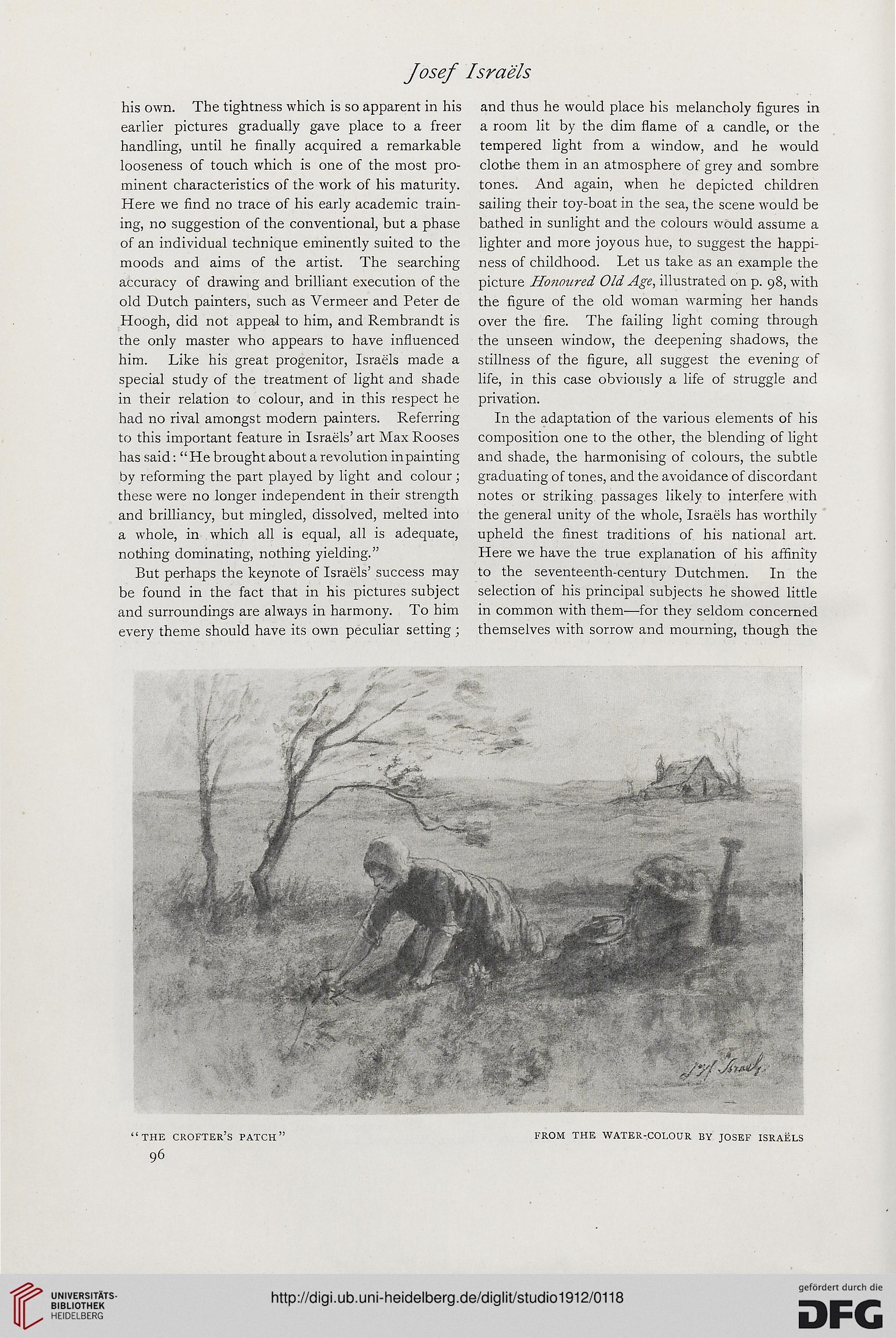

'THE CROFTER'S PATCH" FROM THE WATER-COLOUR BY JOSEF ISRAELS

96

his own. The tightness which is so apparent in his and thus he would place his melancholy figures in

earlier pictures gradually gave place to a freer a room lit by the dim flame of a candle, or the

handling, until he finally acquired a remarkable tempered light from a window, and he would

looseness of touch which is one of the most pro- clothe them in an atmosphere of grey and sombre

minent characteristics of the work of his maturity, tones. And again, when he depicted children

Here we find no trace of his early academic train- sailing their toy-boat in the sea, the scene would be

ing, no suggestion of the conventional, but a phase bathed in sunlight and the colours would assume a

of an individual technique eminently suited to the lighter and more joyous hue, to suggest the happi-

moods and aims of the artist. The searching ness of childhood. Let us take as an example the

accuracy of drawing and brilliant execution of the picture Honoured Old Age, illustrated on p. 98, with

old Dutch painters, such as Vermeer and Peter de the figure of the old woman warming her hands

Hoogh, did not appeal to him, and Rembrandt is over the fire. The failing light coming through

the only master who appears to have influenced the unseen window, the deepening shadows, the

him. Like his great progenitor, Israels made a stillness of the figure, all suggest the evening of

special study of the treatment of light and shade life, in this case obviously a life of struggle and

in their relation to colour, and in this respect he privation.

had no rival amongst modern painters. Referring In the adaptation of the various elements of his

to this important feature in Israels' art Max Rooses composition one to the other, the blending of light

has said: "He brought about a revolution in painting and shade, the harmonising of colours, the subtle

by reforming the part played by light and colour; graduating of tones, and the avoidance of discordant

these were no longer independent in their strength notes or striking passages likely to interfere with

and brilliancy, but mingled, dissolved, melted into the general unity of the whole, Israels has worthily

a whole, in which all is equal, all is adequate, upheld the finest traditions of his national art.

nothing dominating, nothing yielding." Here we have the true explanation of his affinity

But perhaps the keynote of Israels' success may to the seventeenth-century Dutchmen. In the

be found in the fact that in his pictures subject selection of his principal subjects he showed little

and surroundings are always in harmony. To him in common with them-—for they seldom concerned

every theme should have its own peculiar setting ; themselves with sorrow and mourning, though the

'THE CROFTER'S PATCH" FROM THE WATER-COLOUR BY JOSEF ISRAELS

96