Dutch Pictures for South Africa

tion of the Dutch revelation, with its substantiality after a long period of oblivion. There is always, of

of form which cannot be blown away, and its course, the closest inter-dependence between style

simplicity of style. and intention in art, but the most significant in-

It is the sensibility of the Dutch and Flemish tentions of artists may often be almost unconscious,

artists that is generally overlooked. It is not always We are often inclined to credit artistic results with

remembered that the mirror-like qualities of their being more intentional than they really were. Thus

art represents this sensibility. In their still-life Hals's method, which is almost entirely the result of

pieces we only see one aspect of it, it shows itself reason and logic when applied again by a Sargent,

more profoundly in a portrait by Rembrandt—in a was with Hals instinctive, and we might almost say

receptiveness of attitude on his part towards what- immoral in its anxiety to arrive at results satisfactory

ever may have been stirring in the mind of his sitter, to an exacting sitter, with the minimum of expendi-

which in his own time was absolutely new to art. It ture of time to Hals. He arrived at breadth of style

is less sensitive in Hals, but Hals's eager interest in less by intention than through the embarrassment

his sitter is something to contrast with everything of over-employment. He found the only way

that preceded it. In a Hals portrait it is Hals which while meeting the necessity for rapid

himself who disappears in the revelation of human spontaneous work did not fail in the expression of

character, whereas in all Italian portraiture the that refinement of vision which was his artist's

portrait painter seems to stand beside his work birthright. An Impressionist, which Hals was,

and we are conscious of his artistic personality all cannot fail to include in his Impression everything

the time. However great the picture, its greatness in the order and in the exact degree to which it

is not of that particular kind which excludes from impressed him; and Hals's impressionableness to

the mind of the spectator all sense

that the creation has had an artist

creator. Perhaps it is just here

that the long-sought-for distinction

between realistic and idealistic art

could be found. All realism is

impersonal. And if, as in the case

of Hals, the impersonal artist and

his art are sometimes forgotten for

several generations, it is because,

while successful in challenging

reality, his art fails to introduce

that contrast with reality—that ad-

ditional real thing which it is the

privilege of the highest creation to

add to what is already in the

world.

In art the word " interpretation "

can be used in a wider or narrower

sense. We have shown the inter-

pretation the Dutch school put

upon life in the wider sense, but

there is the narrower use of the

the word as it applies to technical

methods employed by the painter in

translating the scene before him.

Hals's method of interpretation

provides us with the prototype of

the modern impressionist method,

and it was from this fact, and as

the discovery of later artists—and

only afterwards of connoisseurs—

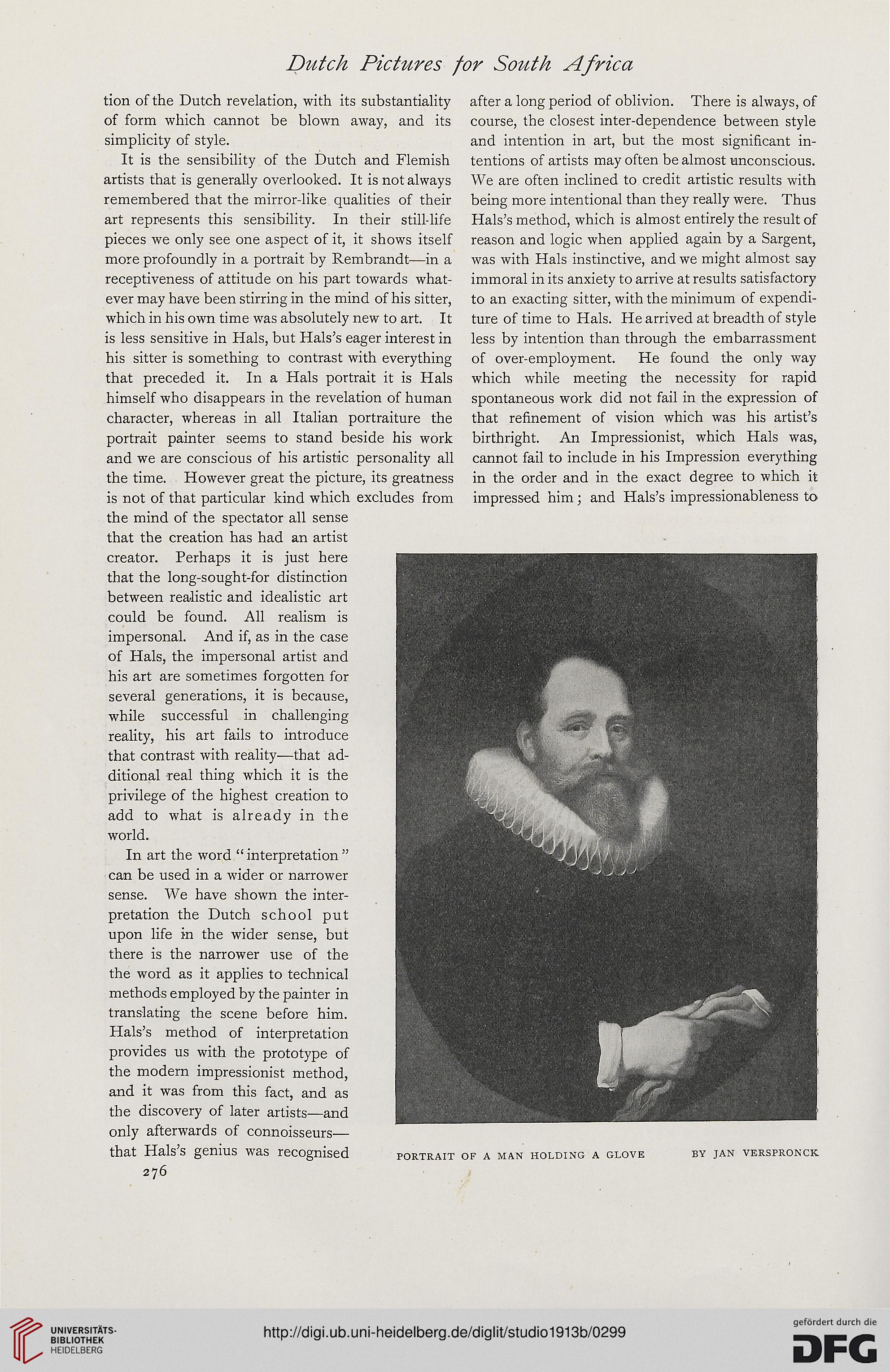

that Hals's genius was recognised portrait of a man holding a glove by jan verspronck

276

tion of the Dutch revelation, with its substantiality after a long period of oblivion. There is always, of

of form which cannot be blown away, and its course, the closest inter-dependence between style

simplicity of style. and intention in art, but the most significant in-

It is the sensibility of the Dutch and Flemish tentions of artists may often be almost unconscious,

artists that is generally overlooked. It is not always We are often inclined to credit artistic results with

remembered that the mirror-like qualities of their being more intentional than they really were. Thus

art represents this sensibility. In their still-life Hals's method, which is almost entirely the result of

pieces we only see one aspect of it, it shows itself reason and logic when applied again by a Sargent,

more profoundly in a portrait by Rembrandt—in a was with Hals instinctive, and we might almost say

receptiveness of attitude on his part towards what- immoral in its anxiety to arrive at results satisfactory

ever may have been stirring in the mind of his sitter, to an exacting sitter, with the minimum of expendi-

which in his own time was absolutely new to art. It ture of time to Hals. He arrived at breadth of style

is less sensitive in Hals, but Hals's eager interest in less by intention than through the embarrassment

his sitter is something to contrast with everything of over-employment. He found the only way

that preceded it. In a Hals portrait it is Hals which while meeting the necessity for rapid

himself who disappears in the revelation of human spontaneous work did not fail in the expression of

character, whereas in all Italian portraiture the that refinement of vision which was his artist's

portrait painter seems to stand beside his work birthright. An Impressionist, which Hals was,

and we are conscious of his artistic personality all cannot fail to include in his Impression everything

the time. However great the picture, its greatness in the order and in the exact degree to which it

is not of that particular kind which excludes from impressed him; and Hals's impressionableness to

the mind of the spectator all sense

that the creation has had an artist

creator. Perhaps it is just here

that the long-sought-for distinction

between realistic and idealistic art

could be found. All realism is

impersonal. And if, as in the case

of Hals, the impersonal artist and

his art are sometimes forgotten for

several generations, it is because,

while successful in challenging

reality, his art fails to introduce

that contrast with reality—that ad-

ditional real thing which it is the

privilege of the highest creation to

add to what is already in the

world.

In art the word " interpretation "

can be used in a wider or narrower

sense. We have shown the inter-

pretation the Dutch school put

upon life in the wider sense, but

there is the narrower use of the

the word as it applies to technical

methods employed by the painter in

translating the scene before him.

Hals's method of interpretation

provides us with the prototype of

the modern impressionist method,

and it was from this fact, and as

the discovery of later artists—and

only afterwards of connoisseurs—

that Hals's genius was recognised portrait of a man holding a glove by jan verspronck

276