THE NEEDLEWORKS IN THE

LADY LEVER ART GALLERY, PORT

SUNLIGHT. 0000

AMONG the many treasures of the

Lady Lever Art Gallery—the imposing

Taj Mahal of the Mersey—one section is

most perfect in the fundamental expression

of the artists' minds, and the medium is—

the little feminine needle. In our near-

sighted age needlework has come to suggest

something sweetly nice and nicely insipid.

A needle, it is assumed, is no match for a

brush. Is this certain i a 0 0

Either in political propaganda or in pure

art essence, the Jacobean ladies show

aesthetic faculties lacking in pigmentary

performances by nineteenth century art

lords in the Gallery. For example. Sir

W. Q. Orchardson painted (excellently)

The Young Duke, being toasted by his

associates, in full-bottomed wigs. Mistress

Damaris Pearse, who died in 1679, aged

20, worked Pharaoh Crossing the Red Sea

(also in full-bottomed wig and technically

perfect). But a sense of aesthetic—that

“face value" of things — led Mistress

Pearse to give variety and vitality to her

figures (notably a mermaid, sewed proper,

vert, rampant, with hand-mirror argent),

and to desert the brush lord in the matter

of noses. The long row of The Young

Duke’s follower's noses has not the obvious

nasal symphony appearance seen in Assy-

rian or Maya sculpture, but a mournful

monotony born of accident. Fate placed

these be-wigged masterpieces in the same

gallery to demonstrate the need for

imagination and a sense of humour in

art. 000000

In draughtsmanship the needleworks

are naively brilliant. The highly-modelled

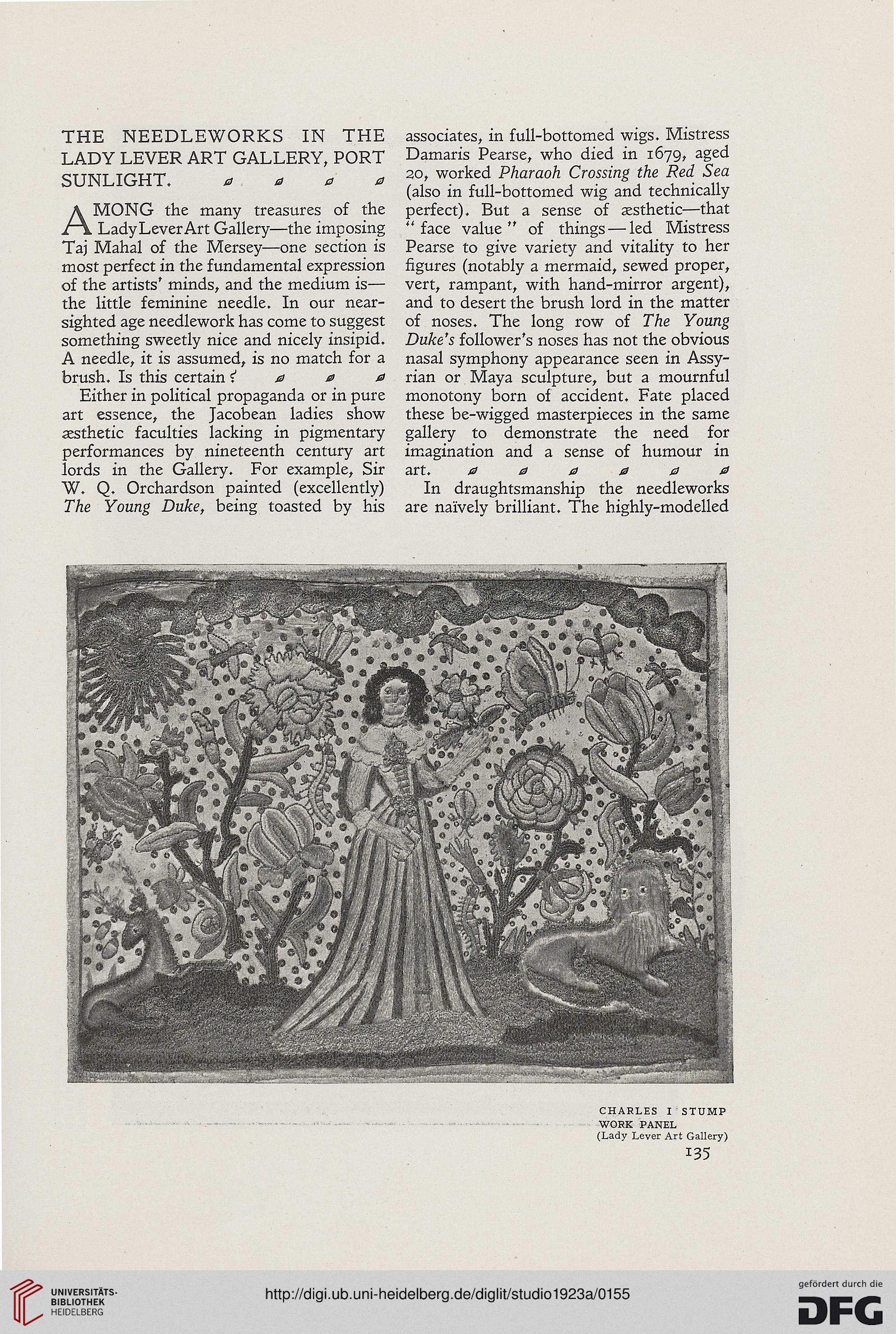

CHARLES I STOMP

WORK PANEL

(Lady Lever Art Gallery)

135

LADY LEVER ART GALLERY, PORT

SUNLIGHT. 0000

AMONG the many treasures of the

Lady Lever Art Gallery—the imposing

Taj Mahal of the Mersey—one section is

most perfect in the fundamental expression

of the artists' minds, and the medium is—

the little feminine needle. In our near-

sighted age needlework has come to suggest

something sweetly nice and nicely insipid.

A needle, it is assumed, is no match for a

brush. Is this certain i a 0 0

Either in political propaganda or in pure

art essence, the Jacobean ladies show

aesthetic faculties lacking in pigmentary

performances by nineteenth century art

lords in the Gallery. For example. Sir

W. Q. Orchardson painted (excellently)

The Young Duke, being toasted by his

associates, in full-bottomed wigs. Mistress

Damaris Pearse, who died in 1679, aged

20, worked Pharaoh Crossing the Red Sea

(also in full-bottomed wig and technically

perfect). But a sense of aesthetic—that

“face value" of things — led Mistress

Pearse to give variety and vitality to her

figures (notably a mermaid, sewed proper,

vert, rampant, with hand-mirror argent),

and to desert the brush lord in the matter

of noses. The long row of The Young

Duke’s follower's noses has not the obvious

nasal symphony appearance seen in Assy-

rian or Maya sculpture, but a mournful

monotony born of accident. Fate placed

these be-wigged masterpieces in the same

gallery to demonstrate the need for

imagination and a sense of humour in

art. 000000

In draughtsmanship the needleworks

are naively brilliant. The highly-modelled

CHARLES I STOMP

WORK PANEL

(Lady Lever Art Gallery)

135