Introduction

Hartmann von Aue's Iwein is – after Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival (and before Gottfried von Straßburg's Tristan) – the second most frequently handed down work from the German courtly literature of the 12th and 13th centuries. 15 extant complete manuscripts and 20 fragments, ranging from the 1220s to the 1530s, document the considerable distribution of this Arthurian romance, and its persistent interest to readers over a long period of time.

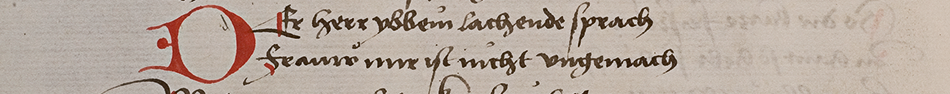

The existence of two largely complete manuscripts Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. Germ 397 [A] and Gießen, Hs. 97 [B]) from the 1220s or 1230s, i.e., a quarter of a century after the composition of the work, and the fact that the later manuscript tradition shows a comparably high textual stability, have shaped textual criticism and editorial history of this Middle High German ‘classic’ from the beginning. The first edition of Iwein by Karl Lachmann and Georg Friedrich Benecke from 1827, was based on manuscript A with regard to verse structure, but on manuscript B regarding the linguistic form. Since then, these early and so to say authoritative manuscripts have held a privileged position. In almost 200 years of research history, the rest of the textual evidence has been largely ignored. This also applies to the latest editions which adhere entirely to manuscript B, while the edition of Benecke and Lachmann (based on A) has retained relevance thanks to reeditions.

Thus the available editions based on A and/or B provide usable versions of the text, probably close to the author’s original, that have proven themselves useful in research and teaching. The fact that A and B offer two very old, and presumably reliable witnesses makes literary-historical analysis much easier than in the case of other courtly romances. The current editiorial situation nonetheless shows two deficits, which could at the same time be considered as desiderata:

- On the one hand, the still canonical position of the Benecke/Lachmann edition of Iwein should perhaps be reconsidered, insofar as the constitution of a 'critical' text which this edition (and its later versions) undertakes has been discredited for several decades now. At present, it is doubtful whether Lachmann's method is at all suitable for medieval vernacular poetry. At the very least, its appropriateness must be reconsidered for each individual text.

- On the other hand, the discipline has been convinced for nearly 50 years now, that not only the author-related versions or texts deserve attention, but also the further ‘life’ of the texts as part of the process of textual transmission. This ‘life’ provides information about the handling of courtly literature in the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, and thus becomes an important testimony to literary and cultural history.

Iwein – digital reacts to both of these requirements. For the first time textual history of Iwein is presented completely, clearly and without method-induced distortions of perspective.

- Only on such a basis is it possible to discuss afresh central questions of Iwein’s textual criticism without dogmatic assumptions: the supposed or actual stability of textual transmission, the possibility, or impossibility of establishing a stemma, and the relevance of ‘family relationships’ among witnesses. Earlier research on these matters, which of course had to manage without the help of electronic data processing, came to either no, or contradictory results: relative textual stability but no consensus about a possible stemma. This makes dealing with these questions complex and difficult, but also worthwhile. Observations made here will have a comparative value for other constellations of the German manuscript age.

- Our edition of selected textual witnesses of Iwein, according to uniform standards, will also provide Iwein texts that were not previously available, or only available as digitized versions of manuscripts, for researchers of German medieval studies and related disciplines. This edition also makes it possible to follow the widely ramified textual history of a major courtly romance in a comprehensive way, right up to the tackling of far-reaching literary and cultural-historical questions. For example, the fact that the Iwein is included in the Ambraser Heldenbuch, but also in other contemporary and earlier manuscripts, could help to measure more precisely the critical and literary-historical status of this late but important codex, than would be possible on the basis solely of the texts that are only handed down in the Heldenbuch.

Iwein – digital presents the entire tradition as a testimony as to how Hartmann’s work has been read, maintained and even modified throughout history. It offers the possibility of reading and comparing the various textual testimonies individually, or synoptically side by side, both in the form of "raw" transcriptions of the manuscripts, or in edited form.

Iwein – digital does not intend to offer a critical edition of Iwein. The aim is not to recover a supposed text by Hartmann von Aue; that was the purpose of the Benecke/Lachmann edition and its followers, who persisted for over a century and a half. Nor is this a ‘Leithandschrift’-edition, in which the best and oldest possible textual witness is chosen as the text; that is already achieved by the 21st century paper-editions available in bookshops (Mertens 2004, Edwards 2007, Krohn 2011 and del Duca 2014). Iwein – digital will edit a wide selection of witnesses of Iwein in their current form and make them readable; not all witnesses can be edited, but about half of them can. In addition, the fragments will be edited in their entirety for the first time. The aim of this project is thus to highlight textual variation in the tradition of Iwein and to show how this romance has been read and interpreted over the centuries.