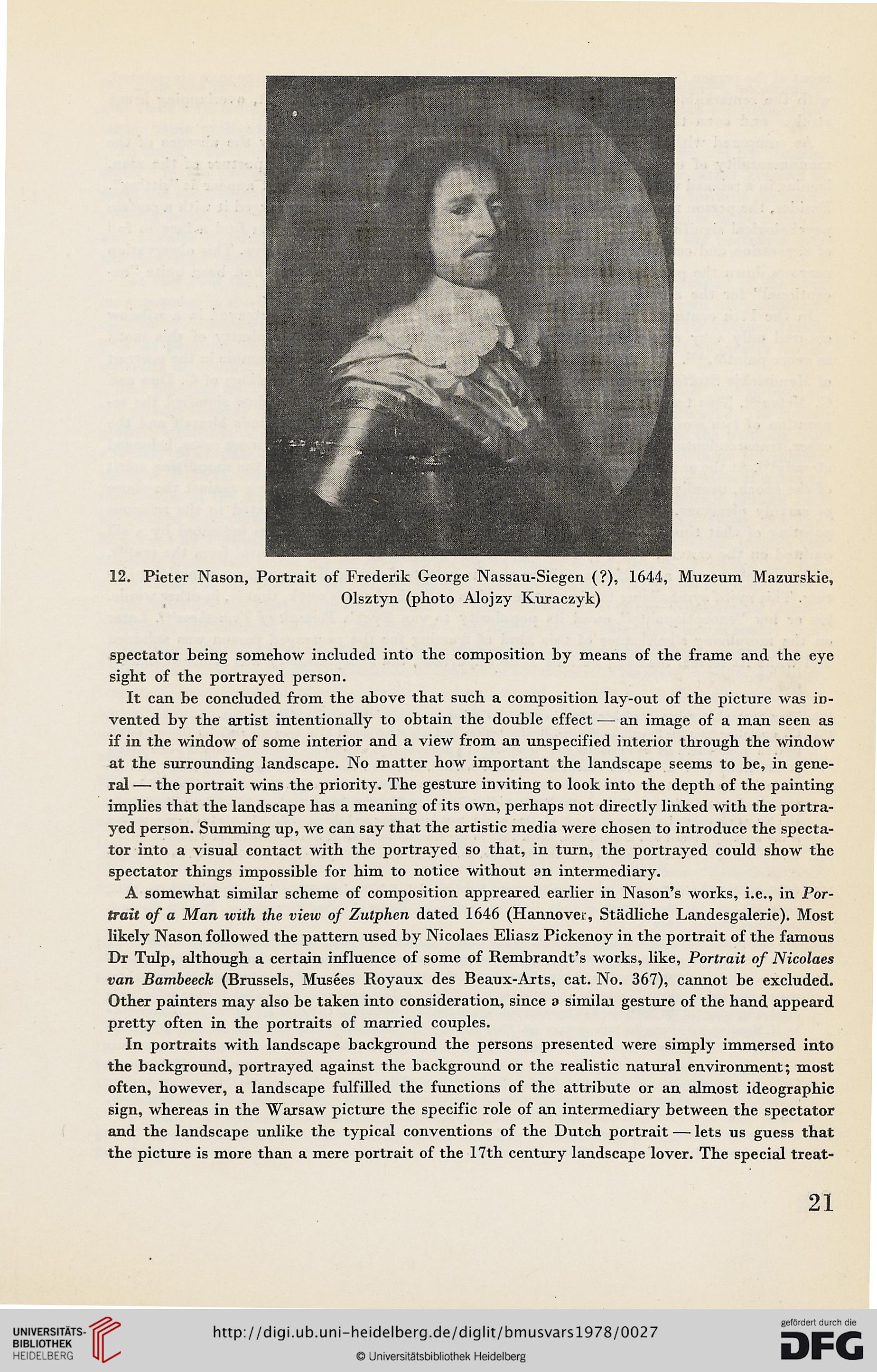

12. Pieter Nason, Portrait of Frederik George Nassau-Siegen (?), 1644, Muzeum Mazurskie,

Olsztyn (photo Alojzy Kuraczyk)

spectator beiug somehow included into the composition by means of the frame and the eye

sight of the portrayed person.

It can be concluded from the above that such a composition lay-out of the picture was in-

vented by the artist intentionally to obtain the double effect — an image of a man seen as

if in the window of some interior and a view from an unspecified interior through the window

at the surrounding landscape. No matter how important the landscape seems to be, in gene-

rał — the portrait wins the priority. The gesture inviting to look into the depth of the painting

implies that the landscape has a meaning of its own, perhaps not directly linked with the portra-

yed person. Summing up, we can say that the artistic media were chosen to introduce the specta-

tor into a visual contact with the portrayed so that, in turn, the portrayed could show the

spectator things impossible for him to notice without an intermediary.

A somewhat similar scheme of composition appreared earlier in Nason's works, i.e., in Por-

trait of a Man with the view of Zutphen dated 1646 (Hannovei:, Stadliche Landesgalerie). Most

likely Nason followed the pattern used by Nicolaes Eliasz Pickenoy in the portrait of the famous

Dr Tulp, although a certain influence of some of Rembrandt's works, like, Portrait of Nicolaes

ran Bambeeck (Brussels, Musees Royaux des Beaux-Arts, cat. No. 367), cannot be excluded.

Other painters may also be taken into consideration, sińce a similai gesture of the hand appeard

pretty often in the portraits of married couples.

In portraits with landscape background the persons presented were simply immersed into

the background, portrayed against the background or the realistic natural environment; most

often, however, a landscape fulfilled the functions of the attribute or an almost ideographic

sign, whereas in the Warsaw picture the specific role of an intermediary between the spectator

and the landscape unlike the typical conventions of the Dutch portrait — lets us guess that

the picture is more than a mere portrait of the 17th century landscape lover. The special treat-

21

Olsztyn (photo Alojzy Kuraczyk)

spectator beiug somehow included into the composition by means of the frame and the eye

sight of the portrayed person.

It can be concluded from the above that such a composition lay-out of the picture was in-

vented by the artist intentionally to obtain the double effect — an image of a man seen as

if in the window of some interior and a view from an unspecified interior through the window

at the surrounding landscape. No matter how important the landscape seems to be, in gene-

rał — the portrait wins the priority. The gesture inviting to look into the depth of the painting

implies that the landscape has a meaning of its own, perhaps not directly linked with the portra-

yed person. Summing up, we can say that the artistic media were chosen to introduce the specta-

tor into a visual contact with the portrayed so that, in turn, the portrayed could show the

spectator things impossible for him to notice without an intermediary.

A somewhat similar scheme of composition appreared earlier in Nason's works, i.e., in Por-

trait of a Man with the view of Zutphen dated 1646 (Hannovei:, Stadliche Landesgalerie). Most

likely Nason followed the pattern used by Nicolaes Eliasz Pickenoy in the portrait of the famous

Dr Tulp, although a certain influence of some of Rembrandt's works, like, Portrait of Nicolaes

ran Bambeeck (Brussels, Musees Royaux des Beaux-Arts, cat. No. 367), cannot be excluded.

Other painters may also be taken into consideration, sińce a similai gesture of the hand appeard

pretty often in the portraits of married couples.

In portraits with landscape background the persons presented were simply immersed into

the background, portrayed against the background or the realistic natural environment; most

often, however, a landscape fulfilled the functions of the attribute or an almost ideographic

sign, whereas in the Warsaw picture the specific role of an intermediary between the spectator

and the landscape unlike the typical conventions of the Dutch portrait — lets us guess that

the picture is more than a mere portrait of the 17th century landscape lover. The special treat-

21