188

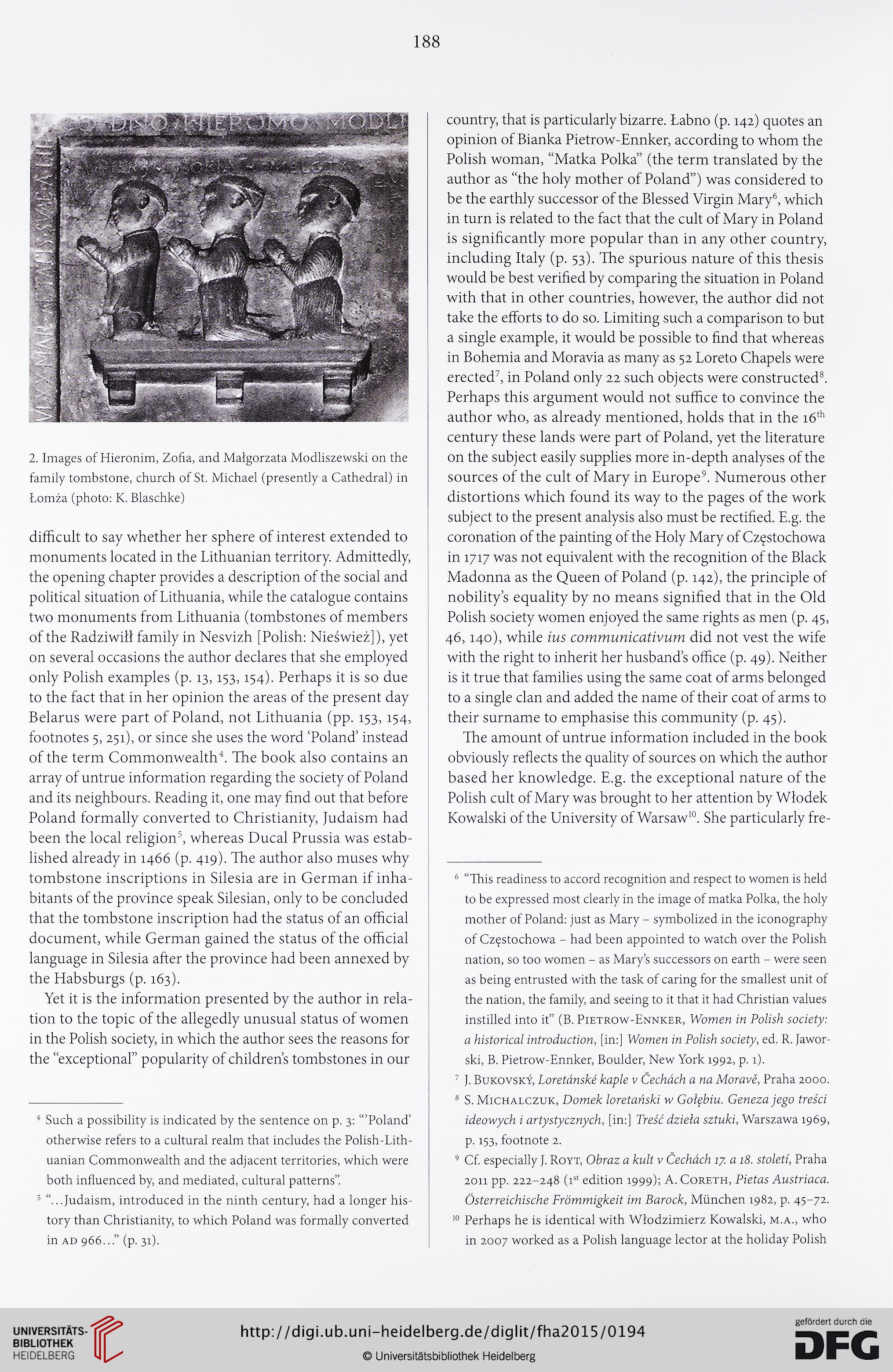

2. Images of Hieronim, Zofia, and Małgorzata Modliszewski on the

family tombstone, church of St. Michael (presently a Cathedral) in

Łomża (photo: K. Blaschke)

difficult to say whcther her sphere of interest extended to

monuments located in the Lithuanian territory. Admittedly,

the opening chapter provides a description of the social and

political situation of Lithuania, while the catalogue contains

two monuments from Lithuania (tombstones of members

of the Radziwiłł family in Nesvizh [Polish: Nieśwież]), yet

on several occasions the author declares that she employed

only Polish examples (p. 13,153,154). Perhaps it is so due

to the fact that in her opinion the areas of the present day

Belarus were part of Poland, not Lithuania (pp. 153, 154,

footnotes 5, 251), or since she uses the word ‘Poland’ instead

of the term Commonwealth 4. The book also contains an

array of untrue information regarding the society of Poland

and its neighbours. Reading it, one may hnd out that before

Poland formally converted to Christianity, Judaism had

been the locał religion 5, whereas Ducal Prussia was estab-

lished already in 1466 (p. 419). The author also muses why

tombstone inscriptions in Silesia are in German if inha-

bitants of the province speak Silesian, only to be concluded

that the tombstone inscription had the status of an official

document, while German gained the status of the official

language in Silesia after the province had been annexed by

the Habsburgs (p. 163).

Yet it is the information presented by the author in rela-

tion to the topic of the allegedly unusual status of women

in the Polish society, in which the author sees the reasons for

the “exceptional” popularity of children’s tombstones in our

4 Such a possibility is indicated by the sentence on p. 3: “’Poland’

otherwise refers to a cultural realm that includes the Polish-Lith-

uanian Commonwealth and the adjacent territories, which were

both influenced by, and mediated, cultural patterns”.

5 “...Judaism, introduced in the ninth century, had a longer his-

tory than Christianity, to which Poland was formally converted

in ad 966...” (p. 31).

country, that is particularly bizarre. Labno (p. 142) quotes an

opinion of Bianka Pietrow-Ennker, according to whom the

Polish woman, “Matka Polka” (the term translated by the

author as “the holy mother of Poland”) was considered to

be the earthly successor of the Blessed Virgin Mary 6 7, which

in turn is related to the fact that the cult of Mary in Poland

is significantly more popular than in any other country,

including Italy (p. 53). The spurious nature of this thesis

would be best verified by comparing the situation in Poland

with that in other countries, however, the author did not

take the efforts to do so. Limiting such a comparison to but

a single example, it would be possible to find that whereas

in Bohemia and Moravia as many as 52 Loreto Chapels were

erected', in Poland only 22 such objects were constructed 8.

Perhaps this argument would not suffice to convince the

author who, as already mentioned, holds that in the 16 th

century these lands were part of Poland, yet the literature

on the subject easily supplies more in-depth analyses of the

sources of the cult of Mary in Europe 9. Numerous other

distortions which found its way to the pages of the work

subject to the present analysis also must be rectified. E.g. the

coronation of the painting of the Holy Mary of Częstochowa

in 1717 was not equivalent with the recognition of the Black

Madonna as the Queen of Poland (p. 142), the principle of

nobility’s equality by no means signified that in the Old

Połish society women enjoyed the same rights as men (p. 45,

46,140), while ius communicativum did not vest the wife

with the right to inherit her husband’s office (p. 49). Neither

is it true that families using the same coat of arms belonged

to a single clan and added the name of their coat of arms to

their surname to emphasise this community (p. 45).

The amount of untrue information included in the book

obviously refiects the quality of sources on which the author

based her knowledge. E.g. the exceptional nature of the

Polish cult of Mary was brought to her attention by Włodek

Kowalski of the University of Warsaw 10. She particularly fre-

6 “This readiness to accord recognition and respect to women is held

to be expressed most clearly in the image of matka Polka, the holy

mother of Poland: just as Mary - symbolized in the iconography

of Częstochowa - had been appointed to watch over the Polish

nation, so too women - as Mary’s successors on earth - were seen

as being entrusted with the task of caring for the smallest unit of

the nation, the family, and seeing to it that it had Christian values

instilled into it” (B. Pietrow-Ennker, Women in Polish society:

a historical introduction, [in:] Women in Polish society, ed. R. Jawor-

ski, B. Pietrow-Ennker, Boulder, New York 1992, p. 1).

7 J. Bukovsky, Loretdnske kaple v Ćechdch a na Morave, Praha 2000.

8 S. Michalczuk, Domek loretański w Gołębiu. Genezajego treści

ideowych i artystycznych, [in:] Treść dzieła sztuki, Warszawa 1969,

p. 153, footnote 2.

9 Cf. especially J. Royt, Obraz a kult v Ćechdch ly. a 18. stoleti, Praha

2011 pp. 222-248 (i st edition 1999); A. Coreth, Pietas Austriaca.

Osterreichische Frómmigkeit im Barock, Miinchen 1982, p. 45-72.

i° perhaps he is identical with Włodzimierz Kowalski, m.a., who

in 2007 worked as a Polish language lector at the holiday Polish

2. Images of Hieronim, Zofia, and Małgorzata Modliszewski on the

family tombstone, church of St. Michael (presently a Cathedral) in

Łomża (photo: K. Blaschke)

difficult to say whcther her sphere of interest extended to

monuments located in the Lithuanian territory. Admittedly,

the opening chapter provides a description of the social and

political situation of Lithuania, while the catalogue contains

two monuments from Lithuania (tombstones of members

of the Radziwiłł family in Nesvizh [Polish: Nieśwież]), yet

on several occasions the author declares that she employed

only Polish examples (p. 13,153,154). Perhaps it is so due

to the fact that in her opinion the areas of the present day

Belarus were part of Poland, not Lithuania (pp. 153, 154,

footnotes 5, 251), or since she uses the word ‘Poland’ instead

of the term Commonwealth 4. The book also contains an

array of untrue information regarding the society of Poland

and its neighbours. Reading it, one may hnd out that before

Poland formally converted to Christianity, Judaism had

been the locał religion 5, whereas Ducal Prussia was estab-

lished already in 1466 (p. 419). The author also muses why

tombstone inscriptions in Silesia are in German if inha-

bitants of the province speak Silesian, only to be concluded

that the tombstone inscription had the status of an official

document, while German gained the status of the official

language in Silesia after the province had been annexed by

the Habsburgs (p. 163).

Yet it is the information presented by the author in rela-

tion to the topic of the allegedly unusual status of women

in the Polish society, in which the author sees the reasons for

the “exceptional” popularity of children’s tombstones in our

4 Such a possibility is indicated by the sentence on p. 3: “’Poland’

otherwise refers to a cultural realm that includes the Polish-Lith-

uanian Commonwealth and the adjacent territories, which were

both influenced by, and mediated, cultural patterns”.

5 “...Judaism, introduced in the ninth century, had a longer his-

tory than Christianity, to which Poland was formally converted

in ad 966...” (p. 31).

country, that is particularly bizarre. Labno (p. 142) quotes an

opinion of Bianka Pietrow-Ennker, according to whom the

Polish woman, “Matka Polka” (the term translated by the

author as “the holy mother of Poland”) was considered to

be the earthly successor of the Blessed Virgin Mary 6 7, which

in turn is related to the fact that the cult of Mary in Poland

is significantly more popular than in any other country,

including Italy (p. 53). The spurious nature of this thesis

would be best verified by comparing the situation in Poland

with that in other countries, however, the author did not

take the efforts to do so. Limiting such a comparison to but

a single example, it would be possible to find that whereas

in Bohemia and Moravia as many as 52 Loreto Chapels were

erected', in Poland only 22 such objects were constructed 8.

Perhaps this argument would not suffice to convince the

author who, as already mentioned, holds that in the 16 th

century these lands were part of Poland, yet the literature

on the subject easily supplies more in-depth analyses of the

sources of the cult of Mary in Europe 9. Numerous other

distortions which found its way to the pages of the work

subject to the present analysis also must be rectified. E.g. the

coronation of the painting of the Holy Mary of Częstochowa

in 1717 was not equivalent with the recognition of the Black

Madonna as the Queen of Poland (p. 142), the principle of

nobility’s equality by no means signified that in the Old

Połish society women enjoyed the same rights as men (p. 45,

46,140), while ius communicativum did not vest the wife

with the right to inherit her husband’s office (p. 49). Neither

is it true that families using the same coat of arms belonged

to a single clan and added the name of their coat of arms to

their surname to emphasise this community (p. 45).

The amount of untrue information included in the book

obviously refiects the quality of sources on which the author

based her knowledge. E.g. the exceptional nature of the

Polish cult of Mary was brought to her attention by Włodek

Kowalski of the University of Warsaw 10. She particularly fre-

6 “This readiness to accord recognition and respect to women is held

to be expressed most clearly in the image of matka Polka, the holy

mother of Poland: just as Mary - symbolized in the iconography

of Częstochowa - had been appointed to watch over the Polish

nation, so too women - as Mary’s successors on earth - were seen

as being entrusted with the task of caring for the smallest unit of

the nation, the family, and seeing to it that it had Christian values

instilled into it” (B. Pietrow-Ennker, Women in Polish society:

a historical introduction, [in:] Women in Polish society, ed. R. Jawor-

ski, B. Pietrow-Ennker, Boulder, New York 1992, p. 1).

7 J. Bukovsky, Loretdnske kaple v Ćechdch a na Morave, Praha 2000.

8 S. Michalczuk, Domek loretański w Gołębiu. Genezajego treści

ideowych i artystycznych, [in:] Treść dzieła sztuki, Warszawa 1969,

p. 153, footnote 2.

9 Cf. especially J. Royt, Obraz a kult v Ćechdch ly. a 18. stoleti, Praha

2011 pp. 222-248 (i st edition 1999); A. Coreth, Pietas Austriaca.

Osterreichische Frómmigkeit im Barock, Miinchen 1982, p. 45-72.

i° perhaps he is identical with Włodzimierz Kowalski, m.a., who

in 2007 worked as a Polish language lector at the holiday Polish