195

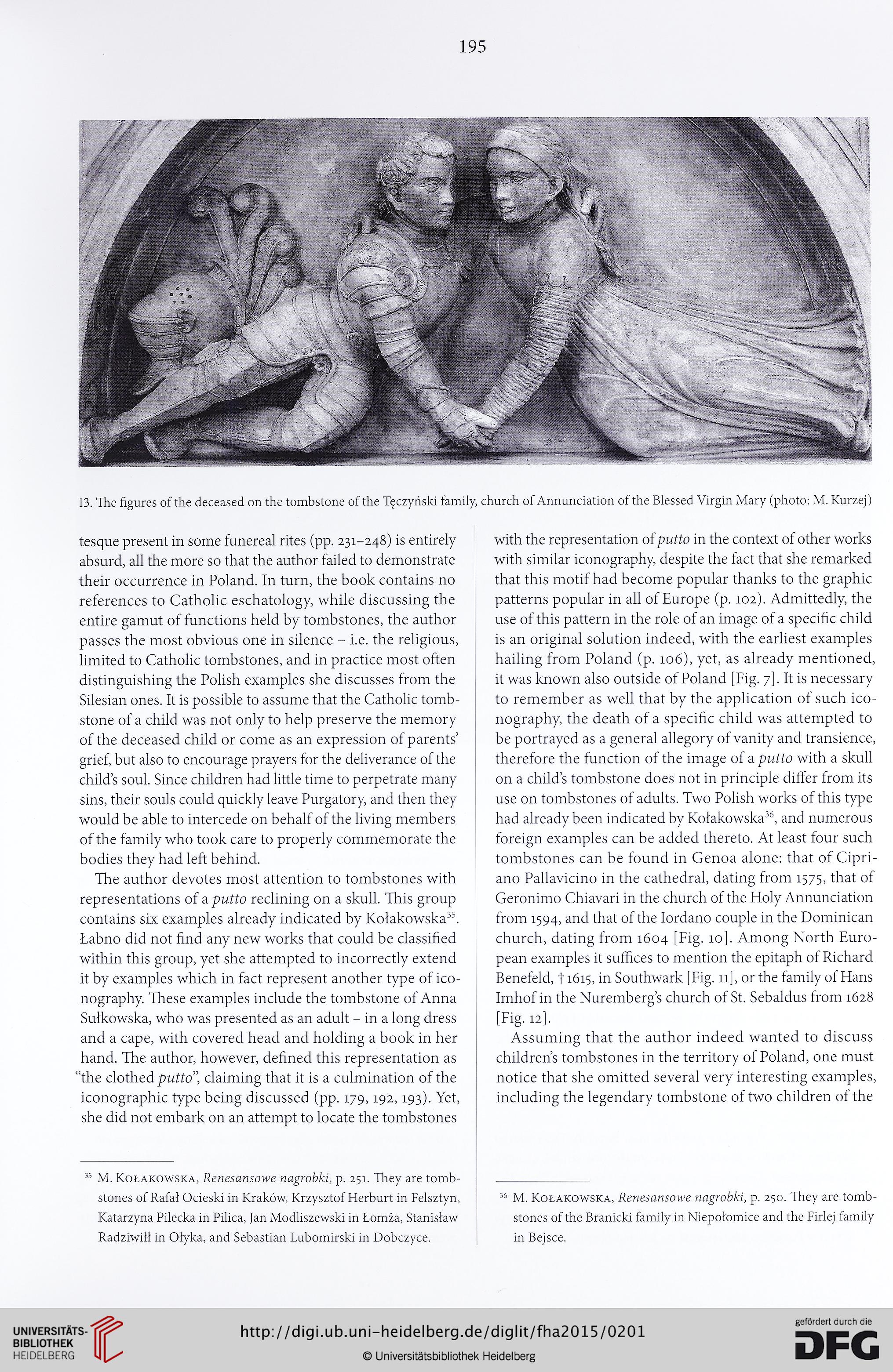

13. The figures of the deceased on the tombstone of the Tęczyński family, church of Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (photo: M. Kurzej)

tesque present in some funereal rites (pp. 231-248) is entirely

absurd, all the more so that the author failed to demonstrate

their occurrence in Poland. In turn, the book contains no

references to Catholic eschatology, while discussing the

entire gamut of functions held by tombstones, the author

passes the most obvious one in silence - i.e. the religious,

limited to Catholic tombstones, and in practice most often

distinguishing the Polish examples she discusses from the

Silesian ones. It is possible to assume that the Catholic tomb-

stone of a child was not only to help preserve the memory

of the deceased child or come as an expression of parents’

grief, but also to encourage prayers for the deliverance of the

childs soul. Since children had little tiine to perpetrate many

sins, their souls could quickly leave Purgatory, and then they

would be able to intercede on behalf of the living members

of the family who took care to properly commemorate the

bodies they had left behind.

The author devotes most attention to tombstones with

representations of a putto reclining on a skull. This group

contains six examples already indicated by KołakowskaC

Łabno did not find any new works that could be classified

within this group, yet she attempted to incorrectly extend

it by examples which in fact represent another type of ico-

nography. These examples include the tombstone of Anna

Sułkowska, who was presented as an adult - in a long dress

and a cape, with covered head and holding a book in her

hand. The author, however, defined this representation as

“the clothed putto’\ claiming that it is a culmination of the

iconographic type being discussed (pp. 179,192,193). Yet,

she did not embark on an attempt to locate the tombstones

35 M. Kołakowska, Renesansowe nagrobki, p. 251. They are tomb-

stones of Rafał Ocieski in Kraków, Krzysztof Herburt in Felsztyn,

Katarzyna Pilecka in Pilica, Jan Modliszewski in Łomża, Stanisław

Radziwiłł in Ołyka, and Sebastian Lubomirski in Dobczyce.

with the representation ofputto in the context of other works

with similar iconography, despite the fact that she remarked

that this motif had become popular thanks to the graphic

patterns popular in all of Europe (p. 102). Admittedly, the

use of this pattern in the role of an image of a specific child

is an original solution indeed, with the earliest examples

hailing from Poland (p. 106), yet, as already mentioned,

it was known also outside of Poland [Fig. 7]. It is necessary

to remember as well that by the application of such ico-

nography, the death of a specific child was attempted to

be portrayed as a general allegory of vanity and transience,

therefore the function of the image of a putto with a skull

on a child’s tombstone does not in principle differ from its

use on tombstones of adults. Two Polish works of this type

had already been indicated by Kołakowska 36, and numerous

foreign examples can be added thereto. At least four such

tombstones can be found in Genoa alone: that of Cipri-

ano Pallavicino in the cathedral, dating from 1575, that of

Geronimo Chiavari in the church of the Holy Annunciation

from 1594, and that of the Iordano couple in the Dominican

church, dating from 1604 [Fig. 10]. Among North Euro-

pean examples it suffices to mention the epitaph of Richard

Benefeld, 11615, in Southwark [Fig. 11], or the family ofHans

Imhof in the Nuremberg’s church of St. Sebaldus from 1628

[Fig. 12].

Assuming that the author indeed wanted to discuss

children’s tombstones in the territory of Poland, one must

notice that she omitted several very interesting examples,

including the legendary tombstone of two children of the

36 M. Kolakowska, Renesansowe nagrobki, p. 250. They are tomb-

stones of the Branicki family in Niepołomice and the Firlej family

in Bejsce.

13. The figures of the deceased on the tombstone of the Tęczyński family, church of Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (photo: M. Kurzej)

tesque present in some funereal rites (pp. 231-248) is entirely

absurd, all the more so that the author failed to demonstrate

their occurrence in Poland. In turn, the book contains no

references to Catholic eschatology, while discussing the

entire gamut of functions held by tombstones, the author

passes the most obvious one in silence - i.e. the religious,

limited to Catholic tombstones, and in practice most often

distinguishing the Polish examples she discusses from the

Silesian ones. It is possible to assume that the Catholic tomb-

stone of a child was not only to help preserve the memory

of the deceased child or come as an expression of parents’

grief, but also to encourage prayers for the deliverance of the

childs soul. Since children had little tiine to perpetrate many

sins, their souls could quickly leave Purgatory, and then they

would be able to intercede on behalf of the living members

of the family who took care to properly commemorate the

bodies they had left behind.

The author devotes most attention to tombstones with

representations of a putto reclining on a skull. This group

contains six examples already indicated by KołakowskaC

Łabno did not find any new works that could be classified

within this group, yet she attempted to incorrectly extend

it by examples which in fact represent another type of ico-

nography. These examples include the tombstone of Anna

Sułkowska, who was presented as an adult - in a long dress

and a cape, with covered head and holding a book in her

hand. The author, however, defined this representation as

“the clothed putto’\ claiming that it is a culmination of the

iconographic type being discussed (pp. 179,192,193). Yet,

she did not embark on an attempt to locate the tombstones

35 M. Kołakowska, Renesansowe nagrobki, p. 251. They are tomb-

stones of Rafał Ocieski in Kraków, Krzysztof Herburt in Felsztyn,

Katarzyna Pilecka in Pilica, Jan Modliszewski in Łomża, Stanisław

Radziwiłł in Ołyka, and Sebastian Lubomirski in Dobczyce.

with the representation ofputto in the context of other works

with similar iconography, despite the fact that she remarked

that this motif had become popular thanks to the graphic

patterns popular in all of Europe (p. 102). Admittedly, the

use of this pattern in the role of an image of a specific child

is an original solution indeed, with the earliest examples

hailing from Poland (p. 106), yet, as already mentioned,

it was known also outside of Poland [Fig. 7]. It is necessary

to remember as well that by the application of such ico-

nography, the death of a specific child was attempted to

be portrayed as a general allegory of vanity and transience,

therefore the function of the image of a putto with a skull

on a child’s tombstone does not in principle differ from its

use on tombstones of adults. Two Polish works of this type

had already been indicated by Kołakowska 36, and numerous

foreign examples can be added thereto. At least four such

tombstones can be found in Genoa alone: that of Cipri-

ano Pallavicino in the cathedral, dating from 1575, that of

Geronimo Chiavari in the church of the Holy Annunciation

from 1594, and that of the Iordano couple in the Dominican

church, dating from 1604 [Fig. 10]. Among North Euro-

pean examples it suffices to mention the epitaph of Richard

Benefeld, 11615, in Southwark [Fig. 11], or the family ofHans

Imhof in the Nuremberg’s church of St. Sebaldus from 1628

[Fig. 12].

Assuming that the author indeed wanted to discuss

children’s tombstones in the territory of Poland, one must

notice that she omitted several very interesting examples,

including the legendary tombstone of two children of the

36 M. Kolakowska, Renesansowe nagrobki, p. 250. They are tomb-

stones of the Branicki family in Niepołomice and the Firlej family

in Bejsce.