William A. Robertson, Master Potter

delicate pieces. It requires patience and skill, an

“enthusiastic patience.” A dragon-fly’s wing or

a tiny flower scarcely loses any of its grace, trans-

lated into this material.

The modern jewelry worker uses stones that are

valuable for their color and decorative quality.

Miss Strange likes best the moonstone and sap-

phire; the former is particularly effective, as it

takes or reflects the colors in the enamels. Cabo-

chon stones combine better with enamel than the

faceted stones.

The large heart-shaped pendant illustrated

is in the most delicious sea-foam shade of green

enamel, with design of apple-blossoms and border

of leaves. Opals and chrysoprases are the stones.

Miss Strange shows great refinement of taste

and variety of design. In her studio, which is

now in Washington, she seems to wave the queer

little tools like magic wands above a table covered

with pretty colored glass, gold, silver and shining

stones, and behold there is fashioned the daintiest,

loveliest things to tempt the feminine heart.

ILLIAM A. ROBERTSON, MAS-

TER POTTER

BY EDITH DUNHAM FOSTER

Five generations of Robertsons

have made things of clay with their hands. Today,

in his pottery in Dedham, Massachusetts, William

A. Robertson, the last potter of his line, watches

the clay as it is thrown onto the wheel, and travels

from the kiln to the decorator, to the bath of glaze

and back to the kiln, until it takes a form that is

one of the distinct contributions of America to

the art of all time. But it is at a fearful price,

paid by five generations, that a Robertson has

learned his supreme mastery of the craft.

Over a century ago, on the rugged hills of Scot-

land, James Robertson fashioned clay into jugs

and pots. His son Hugh made jugs and pots of

clay. Another James was born and a second

Hugh, and they, too, fashioned clay. One by one

they longed for wider fields, and came to America.

Together the Robertsons opened the Chelsea Pot-

tery, near Boston. Hugh and the rest were fast

held by the love of the beautiful in form and

color, and of the common, red, porous clay, which

others thought valueless except for bricks, they

began to model perfect forms after the Greek

vase. But machinery came, and made a vase of

similar form at a quarter the price. So back to the

jugs and pots for daily bread went the beauty-

loving Robertsons. Financial discouragement

was not sufficient to keep them from the deco-

rative branch of the potter’s trade, and, in the

years which followed, they reproduced beau-

tiful forms and pure designs. It was a weary

task, however, for they worked unceasingly but

unavailingly to reproduce the wonders of the

ancient pottery of the Orient. Then there came

a vase from the kiln with a tiny, glowing spot

of pure ruby red—-the dragon’s blood.

Years went by; one by one the Robertsons

dropped off, either dead or in commercial branches

of the manufacture of pottery. Still Hugh plod-

ded on, with only his young son, William, for a

helper, and the vision of the one ruby red spot for

inspiration. Money they had none; makeshifts

they made do the work of modern appliances.

Today may still be seen at the Dedham works the

crude grinding wheel, mounted upon the stand of

an old sewing machine, that was for years the

chief machinery. One dollar each Saturday night

was all the lad William could have. The boy

became restless. Hugh, the father, though still

absorbed in his quest, realized that the lad was

entitled to answer the youthful demand for

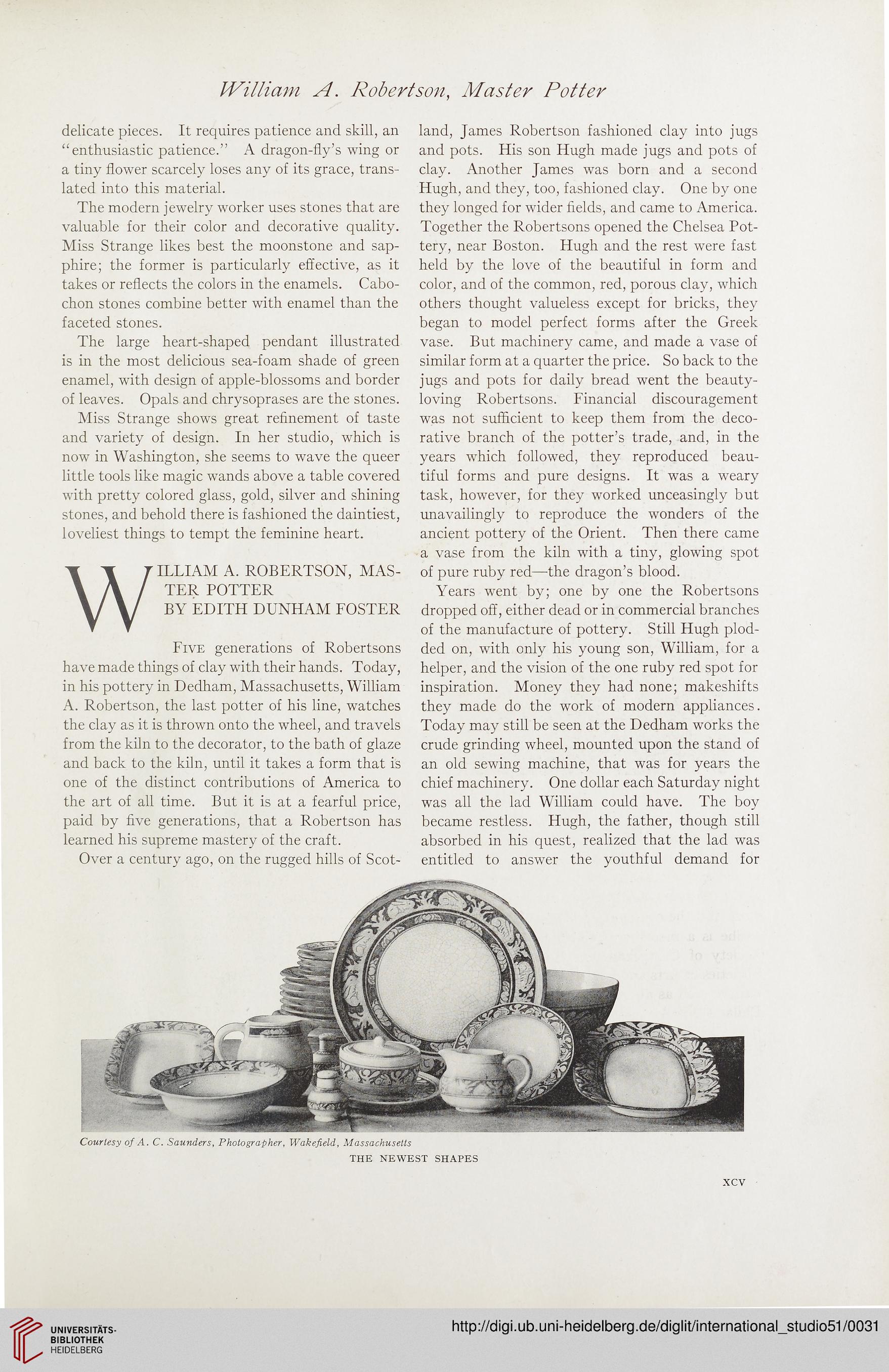

Courtesy of A. C. Saunders, Photographer, Wakefield, Massachusetts

THE NEWEST SHAPES

XCV

delicate pieces. It requires patience and skill, an

“enthusiastic patience.” A dragon-fly’s wing or

a tiny flower scarcely loses any of its grace, trans-

lated into this material.

The modern jewelry worker uses stones that are

valuable for their color and decorative quality.

Miss Strange likes best the moonstone and sap-

phire; the former is particularly effective, as it

takes or reflects the colors in the enamels. Cabo-

chon stones combine better with enamel than the

faceted stones.

The large heart-shaped pendant illustrated

is in the most delicious sea-foam shade of green

enamel, with design of apple-blossoms and border

of leaves. Opals and chrysoprases are the stones.

Miss Strange shows great refinement of taste

and variety of design. In her studio, which is

now in Washington, she seems to wave the queer

little tools like magic wands above a table covered

with pretty colored glass, gold, silver and shining

stones, and behold there is fashioned the daintiest,

loveliest things to tempt the feminine heart.

ILLIAM A. ROBERTSON, MAS-

TER POTTER

BY EDITH DUNHAM FOSTER

Five generations of Robertsons

have made things of clay with their hands. Today,

in his pottery in Dedham, Massachusetts, William

A. Robertson, the last potter of his line, watches

the clay as it is thrown onto the wheel, and travels

from the kiln to the decorator, to the bath of glaze

and back to the kiln, until it takes a form that is

one of the distinct contributions of America to

the art of all time. But it is at a fearful price,

paid by five generations, that a Robertson has

learned his supreme mastery of the craft.

Over a century ago, on the rugged hills of Scot-

land, James Robertson fashioned clay into jugs

and pots. His son Hugh made jugs and pots of

clay. Another James was born and a second

Hugh, and they, too, fashioned clay. One by one

they longed for wider fields, and came to America.

Together the Robertsons opened the Chelsea Pot-

tery, near Boston. Hugh and the rest were fast

held by the love of the beautiful in form and

color, and of the common, red, porous clay, which

others thought valueless except for bricks, they

began to model perfect forms after the Greek

vase. But machinery came, and made a vase of

similar form at a quarter the price. So back to the

jugs and pots for daily bread went the beauty-

loving Robertsons. Financial discouragement

was not sufficient to keep them from the deco-

rative branch of the potter’s trade, and, in the

years which followed, they reproduced beau-

tiful forms and pure designs. It was a weary

task, however, for they worked unceasingly but

unavailingly to reproduce the wonders of the

ancient pottery of the Orient. Then there came

a vase from the kiln with a tiny, glowing spot

of pure ruby red—-the dragon’s blood.

Years went by; one by one the Robertsons

dropped off, either dead or in commercial branches

of the manufacture of pottery. Still Hugh plod-

ded on, with only his young son, William, for a

helper, and the vision of the one ruby red spot for

inspiration. Money they had none; makeshifts

they made do the work of modern appliances.

Today may still be seen at the Dedham works the

crude grinding wheel, mounted upon the stand of

an old sewing machine, that was for years the

chief machinery. One dollar each Saturday night

was all the lad William could have. The boy

became restless. Hugh, the father, though still

absorbed in his quest, realized that the lad was

entitled to answer the youthful demand for

Courtesy of A. C. Saunders, Photographer, Wakefield, Massachusetts

THE NEWEST SHAPES

XCV