The Paintings of Hilda Fearon

The paintings of miss

HILDA FEARON. BY

CHARLES MARRIOTT.

Looking at the work of Miss Hilda Fearon, and

ignoring for the moment its obvious merits of truth,

sincerity and freshness, one is conscious of a de-

tachment other than artistic and a coolness, if not

coldness, distinct from that resulting from the

preference for cool schemes of colour. Her

pictures are, so to speak, a little frosty in their

manner. Their characteristic subject—an interior

with figures—makes this more apparent. A person

of ordinary sensibility coming into a room is aware,

almost before he takes in the identity of individuals,

of the moral or emotional atmosphere between them.

It is hardly necessary to say that emotional, here,

does not mean sentimental. There is a common

feeling of some sort; something that distinguishes

a roomful of people from persons in a room. In

a picture by Miss Fearon this common feeling is

comparatively lacking ; the identity of individuals

women. If the means of expression in painting were

a natural gift this broad distinction would be as

immediately apparent as is the distinction between

the physical characteristics—the voices, for example

—of men and women. It is the enormous difficulty

of the technique of painting that obscures the

distinction. In learning their craft both men and

women tend to lose, at any rate for a time, their

distinguishing characteristics; but, owing to their

smaller physical capacity, the temporary conceal-

ment of personality is greater for women than for

men. Everybody who has come in close contact

with male and female art students has observed that

the latter are generally more completely absorbed in

their work than the former. At a glance one would

say that the women are more industrious, but that

is only part of the truth. Owing to their greater

physical strength the men are able to carry on their

work and still keep in touch with their personalities

as men and individuals with human interests outside

the studio; but, in becoming serious students of

art, the women, for the moment, cease to be women.

is more apparent than the

emotional atmosphere be-

tween them. Even when

some family relationship is

indicated by the choice of

types, her people are

“strangers yet.” The

reason might be lack of

sensibility or unusual re-

serve or coldness of tem-

perament in the painter,

but it is probably nothing

more than the fact that she

is a woman.

This sounds like a

paradox, because women

are generally warmer and

more intimate than men in

their reactions to life. But

between reactions to life

and their expression in art

lie all the difficulties and

accidents of technique.

The saying that there is no

sex in art is true, if at all,

only of craftsmanship. Art

is the expression of human

personality, and, allowing

that the means of expression

are the same for both sexes,

it remains broadly true that

men are men and women

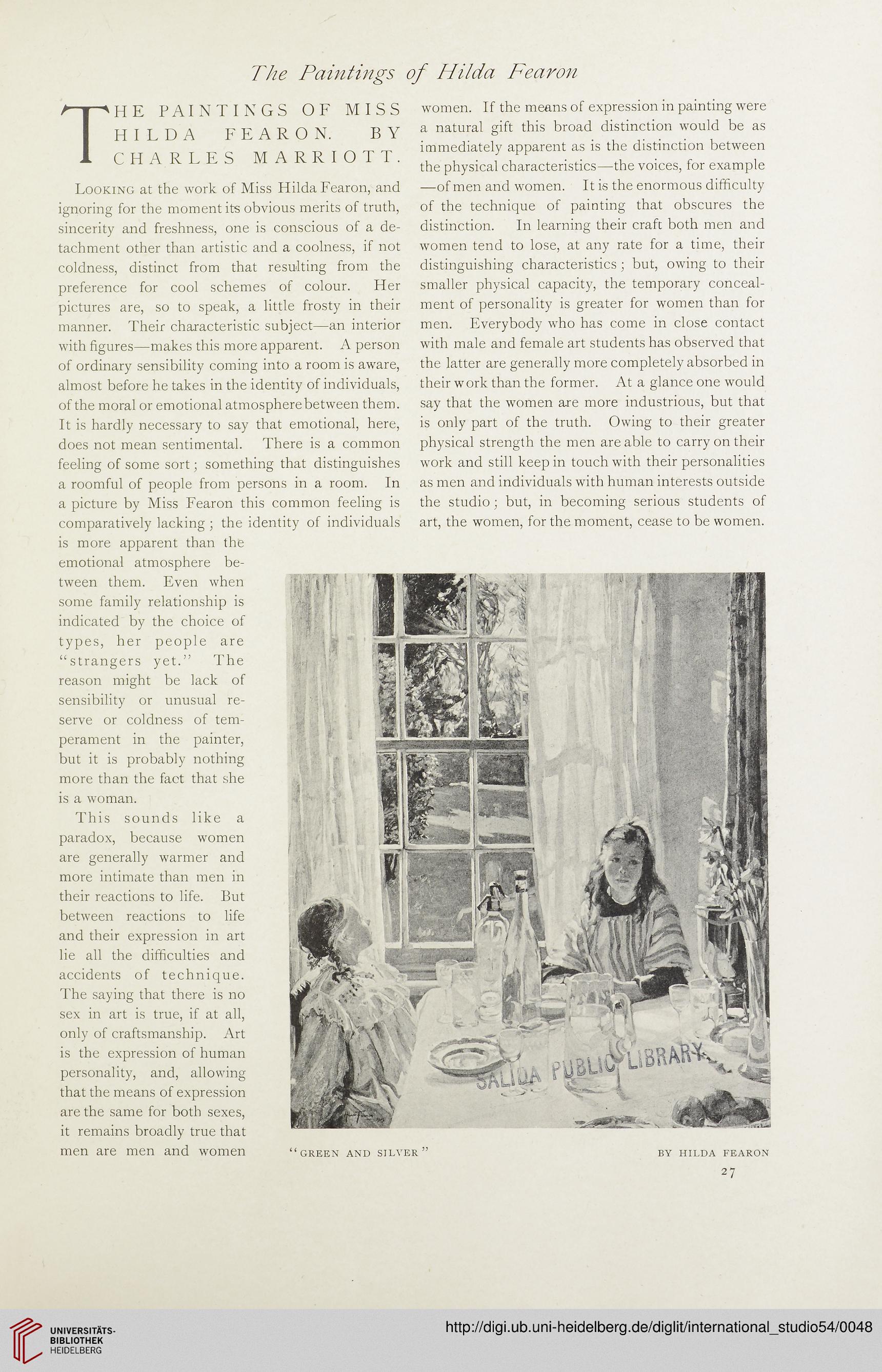

“green and silver”

BY HILDA FEARON

27

The paintings of miss

HILDA FEARON. BY

CHARLES MARRIOTT.

Looking at the work of Miss Hilda Fearon, and

ignoring for the moment its obvious merits of truth,

sincerity and freshness, one is conscious of a de-

tachment other than artistic and a coolness, if not

coldness, distinct from that resulting from the

preference for cool schemes of colour. Her

pictures are, so to speak, a little frosty in their

manner. Their characteristic subject—an interior

with figures—makes this more apparent. A person

of ordinary sensibility coming into a room is aware,

almost before he takes in the identity of individuals,

of the moral or emotional atmosphere between them.

It is hardly necessary to say that emotional, here,

does not mean sentimental. There is a common

feeling of some sort; something that distinguishes

a roomful of people from persons in a room. In

a picture by Miss Fearon this common feeling is

comparatively lacking ; the identity of individuals

women. If the means of expression in painting were

a natural gift this broad distinction would be as

immediately apparent as is the distinction between

the physical characteristics—the voices, for example

—of men and women. It is the enormous difficulty

of the technique of painting that obscures the

distinction. In learning their craft both men and

women tend to lose, at any rate for a time, their

distinguishing characteristics; but, owing to their

smaller physical capacity, the temporary conceal-

ment of personality is greater for women than for

men. Everybody who has come in close contact

with male and female art students has observed that

the latter are generally more completely absorbed in

their work than the former. At a glance one would

say that the women are more industrious, but that

is only part of the truth. Owing to their greater

physical strength the men are able to carry on their

work and still keep in touch with their personalities

as men and individuals with human interests outside

the studio; but, in becoming serious students of

art, the women, for the moment, cease to be women.

is more apparent than the

emotional atmosphere be-

tween them. Even when

some family relationship is

indicated by the choice of

types, her people are

“strangers yet.” The

reason might be lack of

sensibility or unusual re-

serve or coldness of tem-

perament in the painter,

but it is probably nothing

more than the fact that she

is a woman.

This sounds like a

paradox, because women

are generally warmer and

more intimate than men in

their reactions to life. But

between reactions to life

and their expression in art

lie all the difficulties and

accidents of technique.

The saying that there is no

sex in art is true, if at all,

only of craftsmanship. Art

is the expression of human

personality, and, allowing

that the means of expression

are the same for both sexes,

it remains broadly true that

men are men and women

“green and silver”

BY HILDA FEARON

27