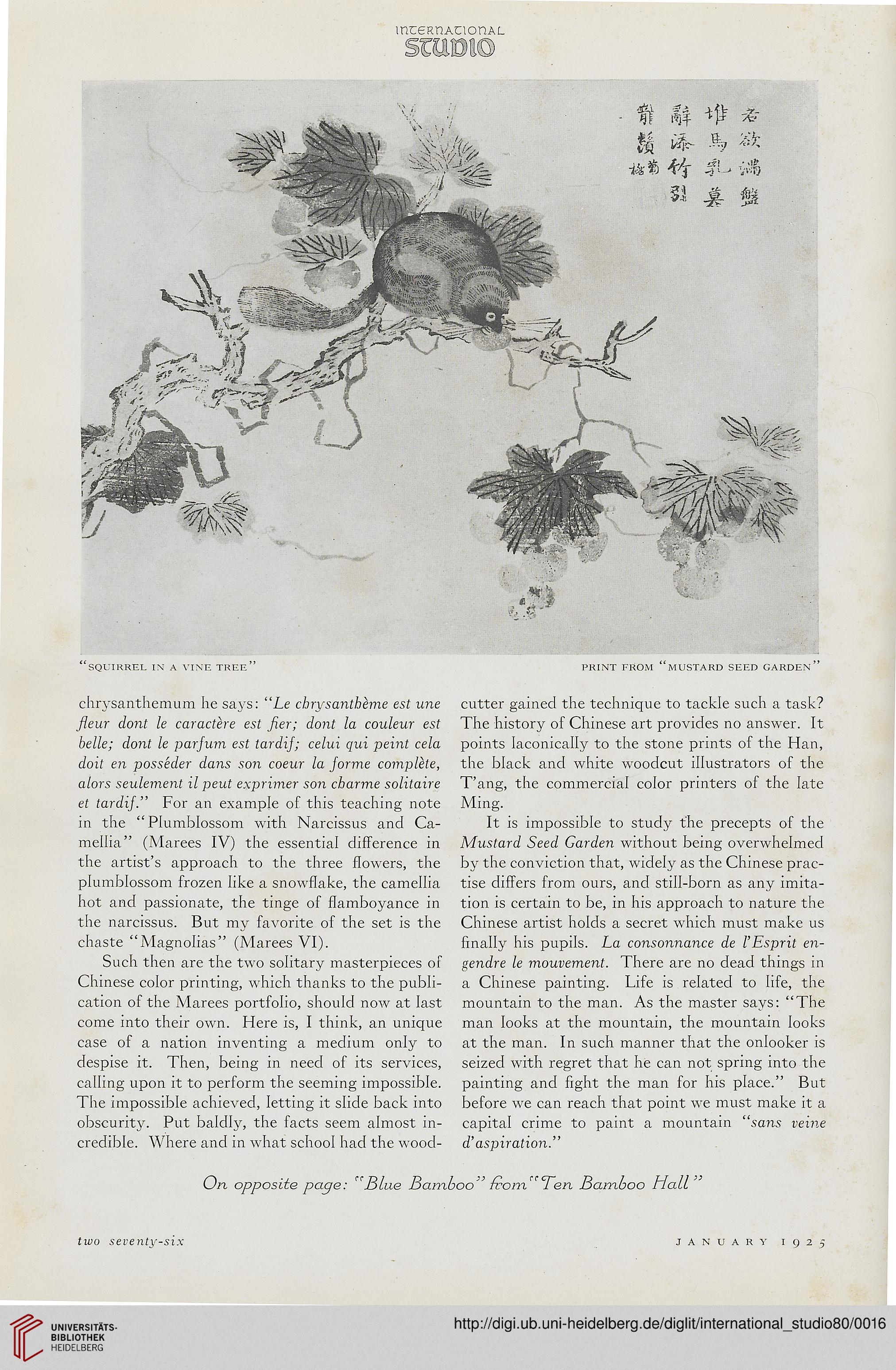

"squirrel in a vine tree"

chrysanthemum he says: "Le cbrysantheme est une

fleur dont le caractere est fier; dont la couleur est

belle; dont le parjum est tardij; celui qui peint cela

doit en posseder dans son coeur la forme complete,

alors seulement il peut exprimer son cbarme solitaire

et tardif." For an example of this teaching note

in the "Plumblossom with Narcissus and Ca-

mellia" (Marees IV) the essential difference in

the artist's approach to the three flowers, the

plumblossom frozen like a snowflake, the camellia

hot and passionate, the tinge of flamboyance in

the narcissus. But my favorite of the set is the

chaste "Magnolias" (Marees VI).

Such then are the two solitary masterpieces of

Chinese color printing, which thanks to the publi-

cation of the Marees portfolio, should now at last

come into their own. Here is, I think, an unique

case of a nation inventing a medium only to

despise it. Then, being in need of its services,

calling upon it to perform the seeming impossible.

The impossible achieved, letting it slide back into

obscurity. Put baldly, the facts seem almost in-

credible. Where and in what school had the wood-

print from "mustard seed garden" "

cutter gamed the technique to tackle such a task?

The history of Chinese art provides no answer. It

points laconically to the stone prints of the Han,

the black and white woodcut illustrators of the

T'ang, the commercial color printers of the late

Ming.

It is impossible to study the precepts of the

Mustard Seed Garden without being overwhelmed

by the conviction that, widely as the Chinese prac-

tise differs from ours, and still-born as any imita-

tion is certain to be, in his approach to nature the

Chinese artist holds a secret which must make us

finally his pupils. La consonnance de I'Esprit en-

gendre le mouvement. There are no dead things in

a Chinese painting. Life is related to life, the

mountain to the man. As the master says: "The

man looks at the mountain, the mountain looks

at the man. In such manner that the onlooker is

seized with regret that he can not spring into the

painting and fight the man for his place." But

before we can reach that point we must make it a

capital crime to paint a mountain "sans veine

d'aspiration."

On opposite page: "Blue Bamboo'' from" Ten Bamboo Hall"

two seventy-six

JANUARY 1925

chrysanthemum he says: "Le cbrysantheme est une

fleur dont le caractere est fier; dont la couleur est

belle; dont le parjum est tardij; celui qui peint cela

doit en posseder dans son coeur la forme complete,

alors seulement il peut exprimer son cbarme solitaire

et tardif." For an example of this teaching note

in the "Plumblossom with Narcissus and Ca-

mellia" (Marees IV) the essential difference in

the artist's approach to the three flowers, the

plumblossom frozen like a snowflake, the camellia

hot and passionate, the tinge of flamboyance in

the narcissus. But my favorite of the set is the

chaste "Magnolias" (Marees VI).

Such then are the two solitary masterpieces of

Chinese color printing, which thanks to the publi-

cation of the Marees portfolio, should now at last

come into their own. Here is, I think, an unique

case of a nation inventing a medium only to

despise it. Then, being in need of its services,

calling upon it to perform the seeming impossible.

The impossible achieved, letting it slide back into

obscurity. Put baldly, the facts seem almost in-

credible. Where and in what school had the wood-

print from "mustard seed garden" "

cutter gamed the technique to tackle such a task?

The history of Chinese art provides no answer. It

points laconically to the stone prints of the Han,

the black and white woodcut illustrators of the

T'ang, the commercial color printers of the late

Ming.

It is impossible to study the precepts of the

Mustard Seed Garden without being overwhelmed

by the conviction that, widely as the Chinese prac-

tise differs from ours, and still-born as any imita-

tion is certain to be, in his approach to nature the

Chinese artist holds a secret which must make us

finally his pupils. La consonnance de I'Esprit en-

gendre le mouvement. There are no dead things in

a Chinese painting. Life is related to life, the

mountain to the man. As the master says: "The

man looks at the mountain, the mountain looks

at the man. In such manner that the onlooker is

seized with regret that he can not spring into the

painting and fight the man for his place." But

before we can reach that point we must make it a

capital crime to paint a mountain "sans veine

d'aspiration."

On opposite page: "Blue Bamboo'' from" Ten Bamboo Hall"

two seventy-six

JANUARY 1925