mceRriAaoriAL

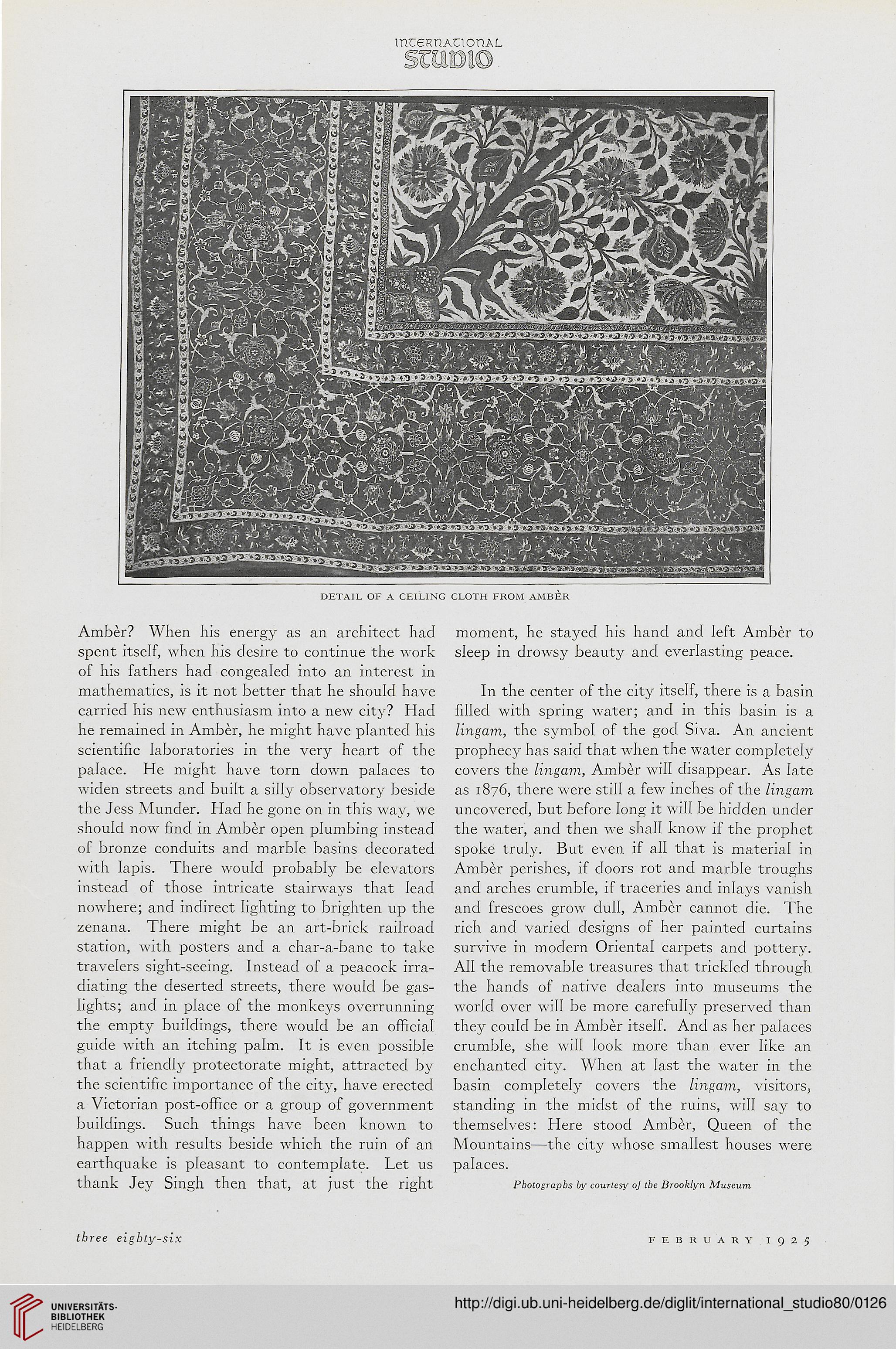

DETAIL OF A CEILING CLOTH FROM AMBER

Amber? When his energy as an architect had

spent itself, when his desire to continue the work

of his fathers had congealed into an interest in

mathematics, is it not better that he should have

carried his new enthusiasm into a new city? Had

he remained in Amber, he might have planted his

scientific laboratories in the very heart of the

palace. He might have torn down palaces to

widen streets and built a silly observatory beside

the Jess Munder. Had he gone on in this wa}r, we

should now find in Amber open plumbing instead

of bronze conduits and marble basins decorated

with lapis. There would probably be elevators

instead of those intricate stairways that lead

nowhere; and indirect lighting to brighten up the

zenana. There might be an art-brick railroad

station, with posters and a char-a-banc to take

travelers sight-seeing. Instead of a peacock irra-

diating the deserted streets, there would be gas-

lights; and in place of the monkeys overrunning

the empty buildings, there would be an official

guide with an itching palm. It is even possible

that a friendly protectorate might, attracted by

the scientific importance of the city, have erected

a Victorian post-office or a group of government

buildings. Such things have been known to

happen with results beside which the ruin of an

earthquake is pleasant to contemplate. Let us

thank Jey Singh then that, at just the right

moment, he stayed his hand and left Amber to

sleep in drowsy beauty and everlasting peace.

In the center of the city itself, there is a basin

filled with spring water; and in this basin is a

lingam, the symbol of the god Siva. An ancient

prophecy has said that when the water completely

covers the lingam, Amber will disappear. As late

as 1876, there were still a few inches of the lingam

uncovered, but before long it will be hidden under

the water, and then we shall know if the prophet

spoke truly. But even if all that is material in

Amber perishes, if doors rot and marble troughs

and arches crumble, if traceries and inlays vanish

and frescoes grow dull, Amber cannot die. The

rich and varied designs of her painted curtains

survive in modern Oriental carpets and pottery.

All the removable treasures that trickled through

the hands of native dealers into museums the

world over will be more carefully preserved than

they could be in Amber itself. And as her palaces

crumble, she will look more than ever like an

enchanted city. When at last the water in the

basin completely covers the lingam, visitors,

standing in the midst of the ruins, will say to

themselves: Here stood Amber, Queen of the

Mountains—the city whose smallest houses were

palaces.

Pbolograpbs by courtesy oj tbc Brooklyn Museum

three eighty-six

FEBRUARY 1925

DETAIL OF A CEILING CLOTH FROM AMBER

Amber? When his energy as an architect had

spent itself, when his desire to continue the work

of his fathers had congealed into an interest in

mathematics, is it not better that he should have

carried his new enthusiasm into a new city? Had

he remained in Amber, he might have planted his

scientific laboratories in the very heart of the

palace. He might have torn down palaces to

widen streets and built a silly observatory beside

the Jess Munder. Had he gone on in this wa}r, we

should now find in Amber open plumbing instead

of bronze conduits and marble basins decorated

with lapis. There would probably be elevators

instead of those intricate stairways that lead

nowhere; and indirect lighting to brighten up the

zenana. There might be an art-brick railroad

station, with posters and a char-a-banc to take

travelers sight-seeing. Instead of a peacock irra-

diating the deserted streets, there would be gas-

lights; and in place of the monkeys overrunning

the empty buildings, there would be an official

guide with an itching palm. It is even possible

that a friendly protectorate might, attracted by

the scientific importance of the city, have erected

a Victorian post-office or a group of government

buildings. Such things have been known to

happen with results beside which the ruin of an

earthquake is pleasant to contemplate. Let us

thank Jey Singh then that, at just the right

moment, he stayed his hand and left Amber to

sleep in drowsy beauty and everlasting peace.

In the center of the city itself, there is a basin

filled with spring water; and in this basin is a

lingam, the symbol of the god Siva. An ancient

prophecy has said that when the water completely

covers the lingam, Amber will disappear. As late

as 1876, there were still a few inches of the lingam

uncovered, but before long it will be hidden under

the water, and then we shall know if the prophet

spoke truly. But even if all that is material in

Amber perishes, if doors rot and marble troughs

and arches crumble, if traceries and inlays vanish

and frescoes grow dull, Amber cannot die. The

rich and varied designs of her painted curtains

survive in modern Oriental carpets and pottery.

All the removable treasures that trickled through

the hands of native dealers into museums the

world over will be more carefully preserved than

they could be in Amber itself. And as her palaces

crumble, she will look more than ever like an

enchanted city. When at last the water in the

basin completely covers the lingam, visitors,

standing in the midst of the ruins, will say to

themselves: Here stood Amber, Queen of the

Mountains—the city whose smallest houses were

palaces.

Pbolograpbs by courtesy oj tbc Brooklyn Museum

three eighty-six

FEBRUARY 1925