mceRHACionAL

us to the future, which join the

imperishable body of art of all

time.

The figure subjects of From kes

do not consciously strive after

the unusual, or attempt obvi-

ously to be "different." It is in

very subtle things, the way the

hand of the Spanish mother

reaches down in a gesture of

tender protection over the baby

in her arms, in the turn a lady

in a black mantilla gives to her

fan, in the shy, upward glance

of a young girl whose carriage

is proud and poised—in these

things Fromkes's portraits have

distinction for not affectation

but sympathy has inspired them.

The landscapes, of which the

reproduction in color of his un-

usual painting of Seville Cathe-

dral across the roof tops is our

only example, are rich in color

and enthusiastic in spirit. They

are not cold, intellectual clisqui-

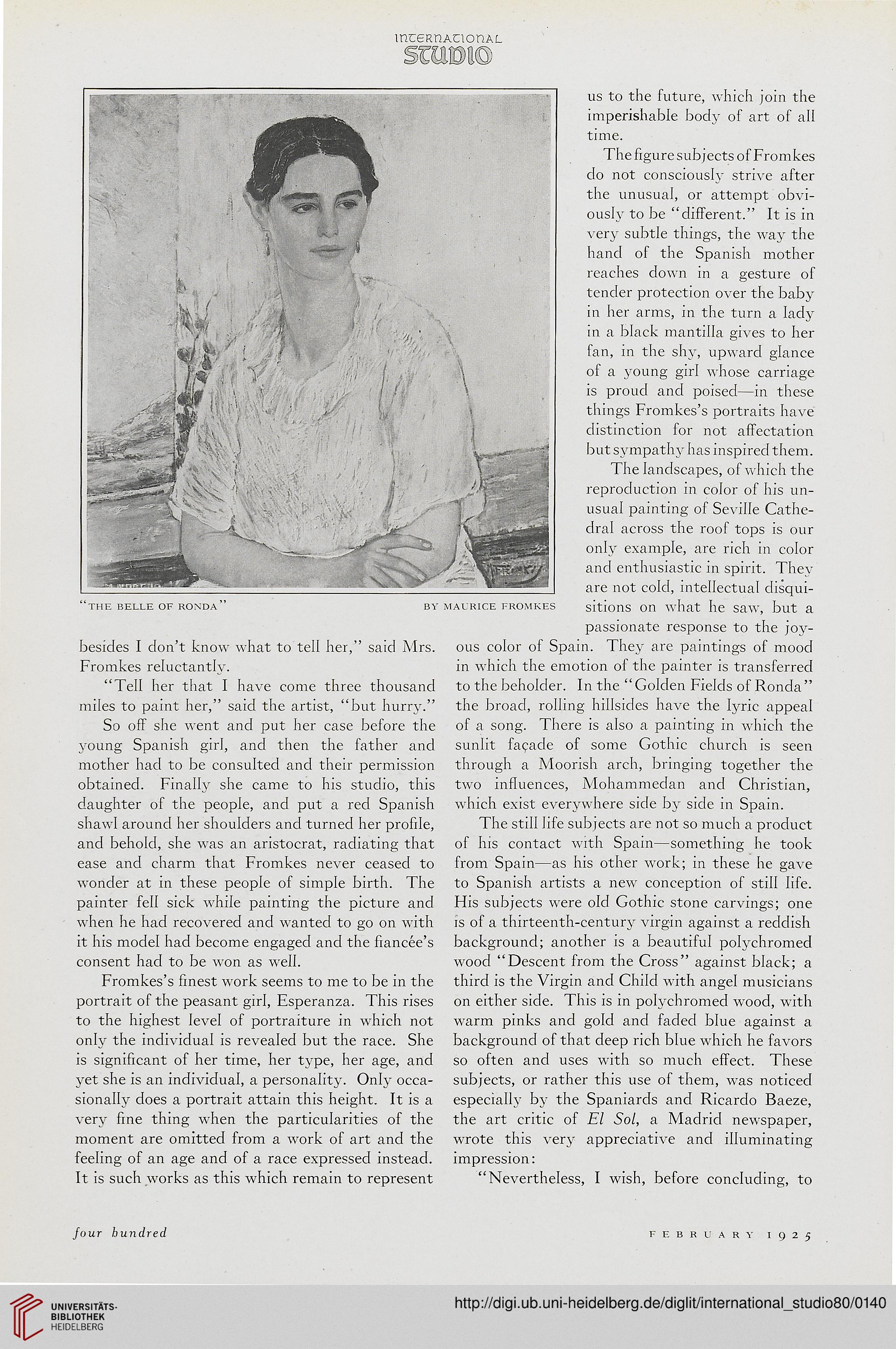

"thebelle ofronda" by maurice fromkes sitions on what he saw, but a

passionate response to the joy-

besides I don't know what to tell her," said Mrs. ous color of Spain. They are paintings of mood

Fromkes reluctantly. in which the emotion of the painter is transferred

"Tell her that I have come three thousand to the beholder. In the " Golden Fields of Ronda"

miles to paint her," said the artist, "but hurry." the broad, rolling hillsides have the lyric appeal

So off she went and put her case before the of a song. There is also a painting in which the

young Spanish girl, and then the father and sunlit facade of some Gothic church is seen

mother had to be consulted and their permission through a Moorish arch, bringing together the

obtained. Finally she came to his studio, this two influences, Mohammedan and Christian,

daughter of the people, and put a red Spanish which exist everywhere side by side in Spain,

shawl around her shoulders and turned her profile, The still life subjects are not so much a product

and behold, she was an aristocrat, radiating that of his contact with Spain—something he took

ease and charm that Fromkes never ceased to from Spain—as his other work; in these he gave

wonder at in these people of simple birth. The to Spanish artists a new conception of still life,

painter fell sick while painting the picture and His subjects were old Gothic stone carvings; one

when he had recovered and wanted to go on with is of a thirteenth-century virgin against a reddish

it his model had become engaged and the fiancee's background; another is a beautiful polychromed

consent had to be won as well. wood "Descent from the Cross" against black; a

Fromkes's finest work seems to me to be in the third is the Virgin and Child with angel musicians

portrait of the peasant girl, Esperanza. This rises on either side. This is in polychromed wood, with

to the highest level of portraiture in which not warm pinks and gold and faded blue against a

only the individual is revealed but the race. She background of that deep rich blue which he favors

is significant of her time, her type, her age, and so often and uses with so much effect. These

yet she is an individual, a personality. Only occa- subjects, or rather this use of them, was noticed

sionally does a portrait attain this height. It is a especially by the Spaniards and Ricardo Baeze,

very fine thing when the particularities of the the art critic of El Sol, a Madrid newspaper,

moment are omitted from a work of art and the wrote this very appreciative and illuminating

feeling of an age and of a race expressed instead, impression:

It is such works as this which remain to represent "Nevertheless, I wish, before concluding, to

Jour hundred

F E B li I A R V I925

us to the future, which join the

imperishable body of art of all

time.

The figure subjects of From kes

do not consciously strive after

the unusual, or attempt obvi-

ously to be "different." It is in

very subtle things, the way the

hand of the Spanish mother

reaches down in a gesture of

tender protection over the baby

in her arms, in the turn a lady

in a black mantilla gives to her

fan, in the shy, upward glance

of a young girl whose carriage

is proud and poised—in these

things Fromkes's portraits have

distinction for not affectation

but sympathy has inspired them.

The landscapes, of which the

reproduction in color of his un-

usual painting of Seville Cathe-

dral across the roof tops is our

only example, are rich in color

and enthusiastic in spirit. They

are not cold, intellectual clisqui-

"thebelle ofronda" by maurice fromkes sitions on what he saw, but a

passionate response to the joy-

besides I don't know what to tell her," said Mrs. ous color of Spain. They are paintings of mood

Fromkes reluctantly. in which the emotion of the painter is transferred

"Tell her that I have come three thousand to the beholder. In the " Golden Fields of Ronda"

miles to paint her," said the artist, "but hurry." the broad, rolling hillsides have the lyric appeal

So off she went and put her case before the of a song. There is also a painting in which the

young Spanish girl, and then the father and sunlit facade of some Gothic church is seen

mother had to be consulted and their permission through a Moorish arch, bringing together the

obtained. Finally she came to his studio, this two influences, Mohammedan and Christian,

daughter of the people, and put a red Spanish which exist everywhere side by side in Spain,

shawl around her shoulders and turned her profile, The still life subjects are not so much a product

and behold, she was an aristocrat, radiating that of his contact with Spain—something he took

ease and charm that Fromkes never ceased to from Spain—as his other work; in these he gave

wonder at in these people of simple birth. The to Spanish artists a new conception of still life,

painter fell sick while painting the picture and His subjects were old Gothic stone carvings; one

when he had recovered and wanted to go on with is of a thirteenth-century virgin against a reddish

it his model had become engaged and the fiancee's background; another is a beautiful polychromed

consent had to be won as well. wood "Descent from the Cross" against black; a

Fromkes's finest work seems to me to be in the third is the Virgin and Child with angel musicians

portrait of the peasant girl, Esperanza. This rises on either side. This is in polychromed wood, with

to the highest level of portraiture in which not warm pinks and gold and faded blue against a

only the individual is revealed but the race. She background of that deep rich blue which he favors

is significant of her time, her type, her age, and so often and uses with so much effect. These

yet she is an individual, a personality. Only occa- subjects, or rather this use of them, was noticed

sionally does a portrait attain this height. It is a especially by the Spaniards and Ricardo Baeze,

very fine thing when the particularities of the the art critic of El Sol, a Madrid newspaper,

moment are omitted from a work of art and the wrote this very appreciative and illuminating

feeling of an age and of a race expressed instead, impression:

It is such works as this which remain to represent "Nevertheless, I wish, before concluding, to

Jour hundred

F E B li I A R V I925