irrcsRnAoonAL

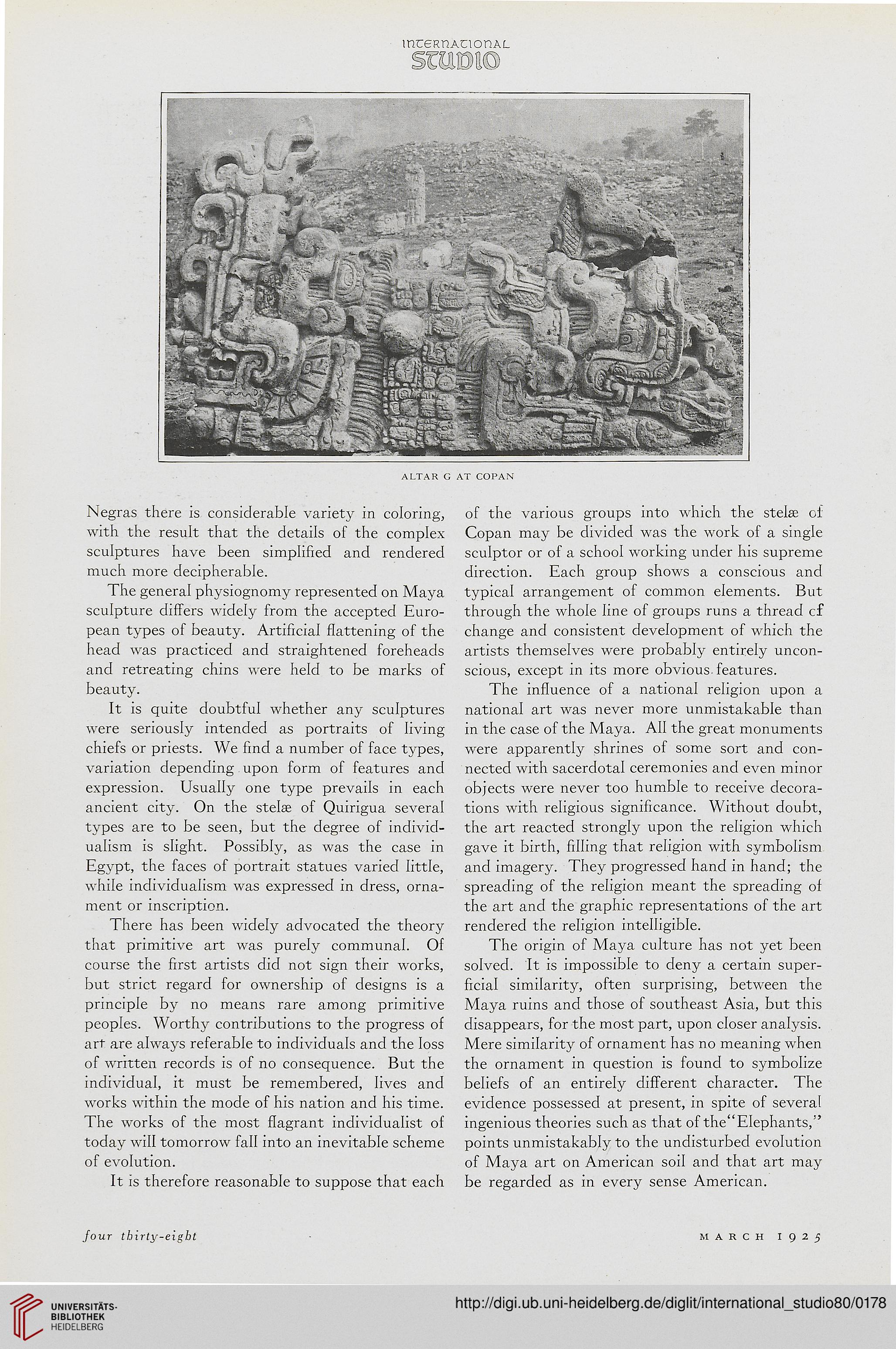

ALTAR C AT COPAN

Negras there is considerable variety in coloring,

with the result that the details of the complex

sculptures have been simplified and rendered

much more decipherable.

The general physiognomy represented on Maya

sculpture differs widely from the accepted Euro-

pean types of beauty. Artificial flattening of the

head was practiced and straightened foreheads

and retreating chins were held to be marks of

beauty.

It is quite doubtful whether any sculptures

were seriously intended as portraits of living

chiefs or priests. We find a number of face types,

variation depending upon form of features and

expression. Usually one type prevails in each

ancient city. On the stela? of Quirigua several

types are to be seen, but the degree of individ-

ualism is slight. Possibly, as was the case in

Egypt, the faces of portrait statues varied little,

while individualism was expressed in dress, orna-

ment or inscription.

There has been widely advocated the theory

that primitive art was purely communal. Of

course the first artists did not sign their works,

but strict regard for ownership of designs is a

principle by no means rare among primitive

peoples. Worthy contributions to the progress of

art are always referable to individuals and the loss

of written records is of no consequence. But the

individual, it must be remembered, lives and

works within the mode of his nation and his time.

The works of the most flagrant individualist of

today will tomorrow fall into an inevitable scheme

of evolution.

It is therefore reasonable to suppose that each

of the various groups into which the stela; of

Copan may be divided was the work of a single

sculptor or of a school working under his supreme

direction. Each group shows a conscious and

typical arrangement of common elements. But

through the whole line of groups runs a thread cf

change and consistent development of which the

artists themselves were probably entirely uncon-

scious, except in its more obvious, features.

The influence of a national religion upon a

national art was never more unmistakable than

in the case of the Maya. All the great monuments

were apparently shrines of some sort and con-

nected with sacerdotal ceremonies and even minor

objects were never too humble to receive decora-

tions with religious significance. Without doubt,

the art reacted strongly upon the religion which

gave it birth, filling that religion with symbolism

and imagery. They progressed hand in hand; the

spreading of the religion meant the spreading of

the art and the graphic representations of the art

rendered the religion intelligible.

The origin of Maya culture has not yet been

solved. It is impossible to deny a certain super-

ficial similarity, often surprising, between the

Maya ruins and those of southeast Asia, but this

disappears, for the most part, upon closer analysis.

Mere similarity of ornament has no meaning when

the ornament in question is found to symbolize

beliefs of an entirely different character. The

evidence possessed at present, in spite of several

ingenious theories such as that of the" Elephants,"

points unmistakably to the undisturbed evolution

of Maya art on American soil and that art may

be regarded as in every sense American.

Jour tbirty-eight

MARCH I925

ALTAR C AT COPAN

Negras there is considerable variety in coloring,

with the result that the details of the complex

sculptures have been simplified and rendered

much more decipherable.

The general physiognomy represented on Maya

sculpture differs widely from the accepted Euro-

pean types of beauty. Artificial flattening of the

head was practiced and straightened foreheads

and retreating chins were held to be marks of

beauty.

It is quite doubtful whether any sculptures

were seriously intended as portraits of living

chiefs or priests. We find a number of face types,

variation depending upon form of features and

expression. Usually one type prevails in each

ancient city. On the stela? of Quirigua several

types are to be seen, but the degree of individ-

ualism is slight. Possibly, as was the case in

Egypt, the faces of portrait statues varied little,

while individualism was expressed in dress, orna-

ment or inscription.

There has been widely advocated the theory

that primitive art was purely communal. Of

course the first artists did not sign their works,

but strict regard for ownership of designs is a

principle by no means rare among primitive

peoples. Worthy contributions to the progress of

art are always referable to individuals and the loss

of written records is of no consequence. But the

individual, it must be remembered, lives and

works within the mode of his nation and his time.

The works of the most flagrant individualist of

today will tomorrow fall into an inevitable scheme

of evolution.

It is therefore reasonable to suppose that each

of the various groups into which the stela; of

Copan may be divided was the work of a single

sculptor or of a school working under his supreme

direction. Each group shows a conscious and

typical arrangement of common elements. But

through the whole line of groups runs a thread cf

change and consistent development of which the

artists themselves were probably entirely uncon-

scious, except in its more obvious, features.

The influence of a national religion upon a

national art was never more unmistakable than

in the case of the Maya. All the great monuments

were apparently shrines of some sort and con-

nected with sacerdotal ceremonies and even minor

objects were never too humble to receive decora-

tions with religious significance. Without doubt,

the art reacted strongly upon the religion which

gave it birth, filling that religion with symbolism

and imagery. They progressed hand in hand; the

spreading of the religion meant the spreading of

the art and the graphic representations of the art

rendered the religion intelligible.

The origin of Maya culture has not yet been

solved. It is impossible to deny a certain super-

ficial similarity, often surprising, between the

Maya ruins and those of southeast Asia, but this

disappears, for the most part, upon closer analysis.

Mere similarity of ornament has no meaning when

the ornament in question is found to symbolize

beliefs of an entirely different character. The

evidence possessed at present, in spite of several

ingenious theories such as that of the" Elephants,"

points unmistakably to the undisturbed evolution

of Maya art on American soil and that art may

be regarded as in every sense American.

Jour tbirty-eight

MARCH I925