mceRnAcionAL

as a coal miner and who painted pictures of Salem

because he must paint something and had no

means to go elsewhere. Once upon a time, so ran

the tale, he saved enough money to journey to

New York and he carried some of his pictures

under his arm up and down Fifth avenue, receiv-

ing nothing but ciiscouragement from the dealers'

galleries until through accident he met the woman

who managed the bookshop. She gave him the

two opportunities to exhibit his work. This legend

accompanied his work to London, where Burch-

field's pictures were first shown in the autumn of

1922, making its appearance in print there as it

may have done at home previously (for it was

told often enough to art writers) without attract-

ing any attention from those in a position to have

first-hand information about Burchfield's career.

In refutation of the romantic legend as pub-

lished in London the art world was informed that

Charles Burchfield was not a self-taught artist, but

had completed a four-year course at the Cleveland

School of Art; that he was not a "miner painting

in his odd moments" but was "employed, at a

good salary, designing wallpaper for one of the

largest manufacturers in the country, who is

appreciative of his work, in which he has taken a

great deal of pleasure." Burchfield's record also

states that from 1919 to 1922 he had exhibited at

the annual shows of the Cleveland Artists and

Craftsmen, winning the first prize in watercolor

and the Penton medal in 1921. Except through

his paintings and watercolors Burchfield is the

least communicative of artists as to his career,

yet I am compelled to believe that he has been a

miner in Salem and is a designer of wallpaper since

that occupation provides him the living that the

sale of his pictures, up to 1922 at least, did not.

From his pictures, which are after all Burch-

field's chief concern and ours as well, he presents

himself as a man so wholly concerned with truth

in one phase of his work as to be a realist of dis-

concerting frankness, while in his second form of

expression he is almost classically romantic.

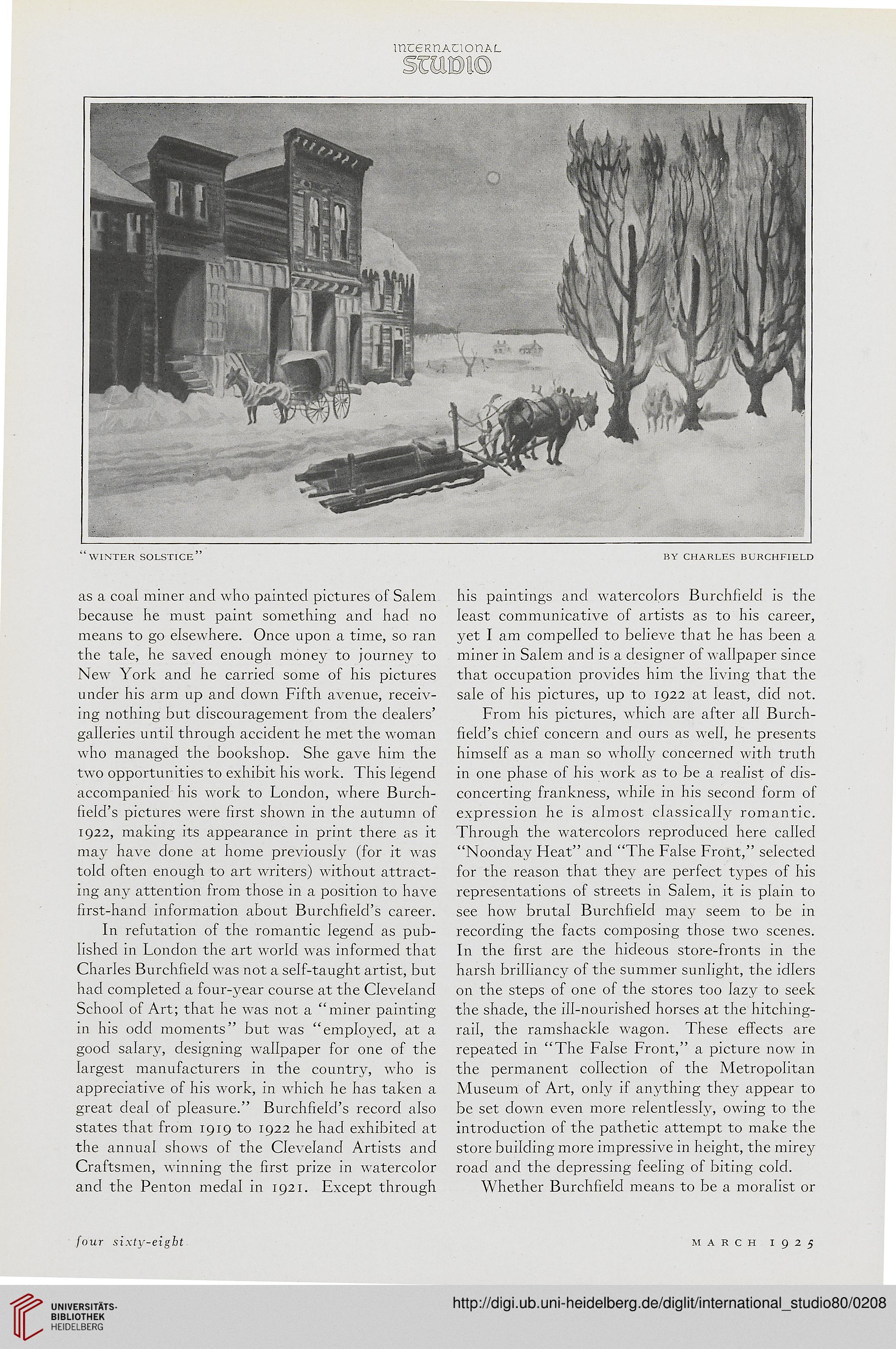

Through the watercolors reproduced here called

"Noonday Heat" and "The False Front," selected

for the reason that they are perfect types of his

representations of streets in Salem, it is plain to

see how brutal Burchfield may seem to be in

recording the facts composing those two scenes.

In the first are the hideous store-fronts in the

harsh brilliancy of the summer sunlight, the idlers

on the steps of one of the stores too lazy to seek

the shade, the ill-nourished horses at the hitching-

rail, the ramshackle wagon. These effects are

repeated in "The False Front," a picture now in

the permanent collection of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, only if anything they appear to

be set down even more relentlessly, owing to the

introduction of the pathetic attempt to make the

store building more impressive in height, the mirey

road and the depressing feeling of biting cold.

Whether Burchfield means to be a moralist or

four sixty-eight

MARCH I925

as a coal miner and who painted pictures of Salem

because he must paint something and had no

means to go elsewhere. Once upon a time, so ran

the tale, he saved enough money to journey to

New York and he carried some of his pictures

under his arm up and down Fifth avenue, receiv-

ing nothing but ciiscouragement from the dealers'

galleries until through accident he met the woman

who managed the bookshop. She gave him the

two opportunities to exhibit his work. This legend

accompanied his work to London, where Burch-

field's pictures were first shown in the autumn of

1922, making its appearance in print there as it

may have done at home previously (for it was

told often enough to art writers) without attract-

ing any attention from those in a position to have

first-hand information about Burchfield's career.

In refutation of the romantic legend as pub-

lished in London the art world was informed that

Charles Burchfield was not a self-taught artist, but

had completed a four-year course at the Cleveland

School of Art; that he was not a "miner painting

in his odd moments" but was "employed, at a

good salary, designing wallpaper for one of the

largest manufacturers in the country, who is

appreciative of his work, in which he has taken a

great deal of pleasure." Burchfield's record also

states that from 1919 to 1922 he had exhibited at

the annual shows of the Cleveland Artists and

Craftsmen, winning the first prize in watercolor

and the Penton medal in 1921. Except through

his paintings and watercolors Burchfield is the

least communicative of artists as to his career,

yet I am compelled to believe that he has been a

miner in Salem and is a designer of wallpaper since

that occupation provides him the living that the

sale of his pictures, up to 1922 at least, did not.

From his pictures, which are after all Burch-

field's chief concern and ours as well, he presents

himself as a man so wholly concerned with truth

in one phase of his work as to be a realist of dis-

concerting frankness, while in his second form of

expression he is almost classically romantic.

Through the watercolors reproduced here called

"Noonday Heat" and "The False Front," selected

for the reason that they are perfect types of his

representations of streets in Salem, it is plain to

see how brutal Burchfield may seem to be in

recording the facts composing those two scenes.

In the first are the hideous store-fronts in the

harsh brilliancy of the summer sunlight, the idlers

on the steps of one of the stores too lazy to seek

the shade, the ill-nourished horses at the hitching-

rail, the ramshackle wagon. These effects are

repeated in "The False Front," a picture now in

the permanent collection of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, only if anything they appear to

be set down even more relentlessly, owing to the

introduction of the pathetic attempt to make the

store building more impressive in height, the mirey

road and the depressing feeling of biting cold.

Whether Burchfield means to be a moralist or

four sixty-eight

MARCH I925