From Gallery, Studio, and Mart

behoves the few remaining aesthetes amongst us to

bestir themselves.

One came away from the interesting show of

Blacksmiths' Work at the Ironmongers' Hall with

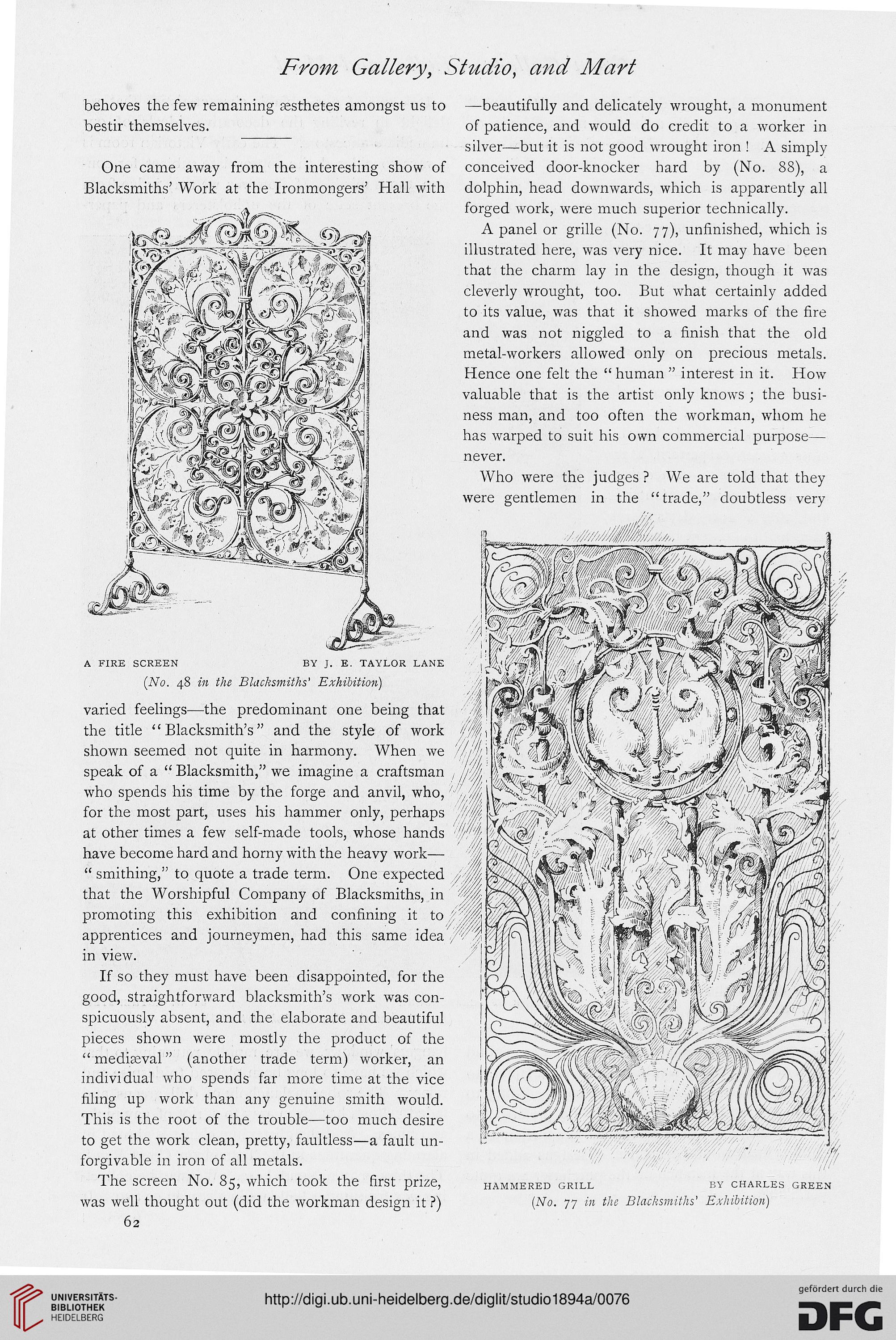

A FIRE SCREEN BY J. E. TAYLOR LANE

(No. 48 in the Blacksmiths' Exhibition)

varied feelings—the predominant one being that

the title "Blacksmith's" and the style of work

shown seemed not quite in harmony. When we

speak of a " Blacksmith," we imagine a craftsman

who spends his time by the forge and anvil, who,

for the most part, uses his hammer only, perhaps

at other times a few self-made tools, whose hands

have become hard and horny with the heavy work—

" smithing," to quote a trade term. One expected

that the Worshipful Company of Blacksmiths, in

promoting this exhibition and confining it to

apprentices and journeymen, had this same idea

in view.

If so they must have been disappointed, for the

good, straightforward blacksmith's work was con-

spicuously absent, and the elaborate and beautiful

pieces shown were mostly the product of the

" mediaeval" (another trade term) worker, an

individual who spends far more time at the vice

filing up work than any genuine smith would.

This is the root of the trouble—too much desire

to get the work clean, pretty, faultless—a fault un-

forgivable in iron of all metals.

The screen No. 85, which took the first prize,

was well thought out (did the workman design it ?)

62

—beautifully and delicately wrought, a monument

of patience, and would do credit to a worker in

silver—but it is not good wrought iron ! A simply

conceived door-knocker hard by (No. 88), a

dolphin, head downwards, which is apparently all

forged work, were much superior technically.

A panel or grille (No. 77), unfinished, which is

illustrated here, was very nice. It may have been

that the charm lay in the design, though it was

cleverly wrought, too. But what certainly added

to its value, was that it showed marks of the fire

and was not niggled to a finish that the old

metal-workers allowed only on precious metals.

Hence one felt the " human " interest in it. How

valuable that is the artist only knows ; the busi-

ness man, and too often the workman, whom he

has warped to suit his own commercial purpose—

never.

Who were the judges ? We are told that they

were gentlemen in the " trade," doubtless very

(No. 77 in the Blacksmiths' Exhibition)

behoves the few remaining aesthetes amongst us to

bestir themselves.

One came away from the interesting show of

Blacksmiths' Work at the Ironmongers' Hall with

A FIRE SCREEN BY J. E. TAYLOR LANE

(No. 48 in the Blacksmiths' Exhibition)

varied feelings—the predominant one being that

the title "Blacksmith's" and the style of work

shown seemed not quite in harmony. When we

speak of a " Blacksmith," we imagine a craftsman

who spends his time by the forge and anvil, who,

for the most part, uses his hammer only, perhaps

at other times a few self-made tools, whose hands

have become hard and horny with the heavy work—

" smithing," to quote a trade term. One expected

that the Worshipful Company of Blacksmiths, in

promoting this exhibition and confining it to

apprentices and journeymen, had this same idea

in view.

If so they must have been disappointed, for the

good, straightforward blacksmith's work was con-

spicuously absent, and the elaborate and beautiful

pieces shown were mostly the product of the

" mediaeval" (another trade term) worker, an

individual who spends far more time at the vice

filing up work than any genuine smith would.

This is the root of the trouble—too much desire

to get the work clean, pretty, faultless—a fault un-

forgivable in iron of all metals.

The screen No. 85, which took the first prize,

was well thought out (did the workman design it ?)

62

—beautifully and delicately wrought, a monument

of patience, and would do credit to a worker in

silver—but it is not good wrought iron ! A simply

conceived door-knocker hard by (No. 88), a

dolphin, head downwards, which is apparently all

forged work, were much superior technically.

A panel or grille (No. 77), unfinished, which is

illustrated here, was very nice. It may have been

that the charm lay in the design, though it was

cleverly wrought, too. But what certainly added

to its value, was that it showed marks of the fire

and was not niggled to a finish that the old

metal-workers allowed only on precious metals.

Hence one felt the " human " interest in it. How

valuable that is the artist only knows ; the busi-

ness man, and too often the workman, whom he

has warped to suit his own commercial purpose—

never.

Who were the judges ? We are told that they

were gentlemen in the " trade," doubtless very

(No. 77 in the Blacksmiths' Exhibition)