Stencilling

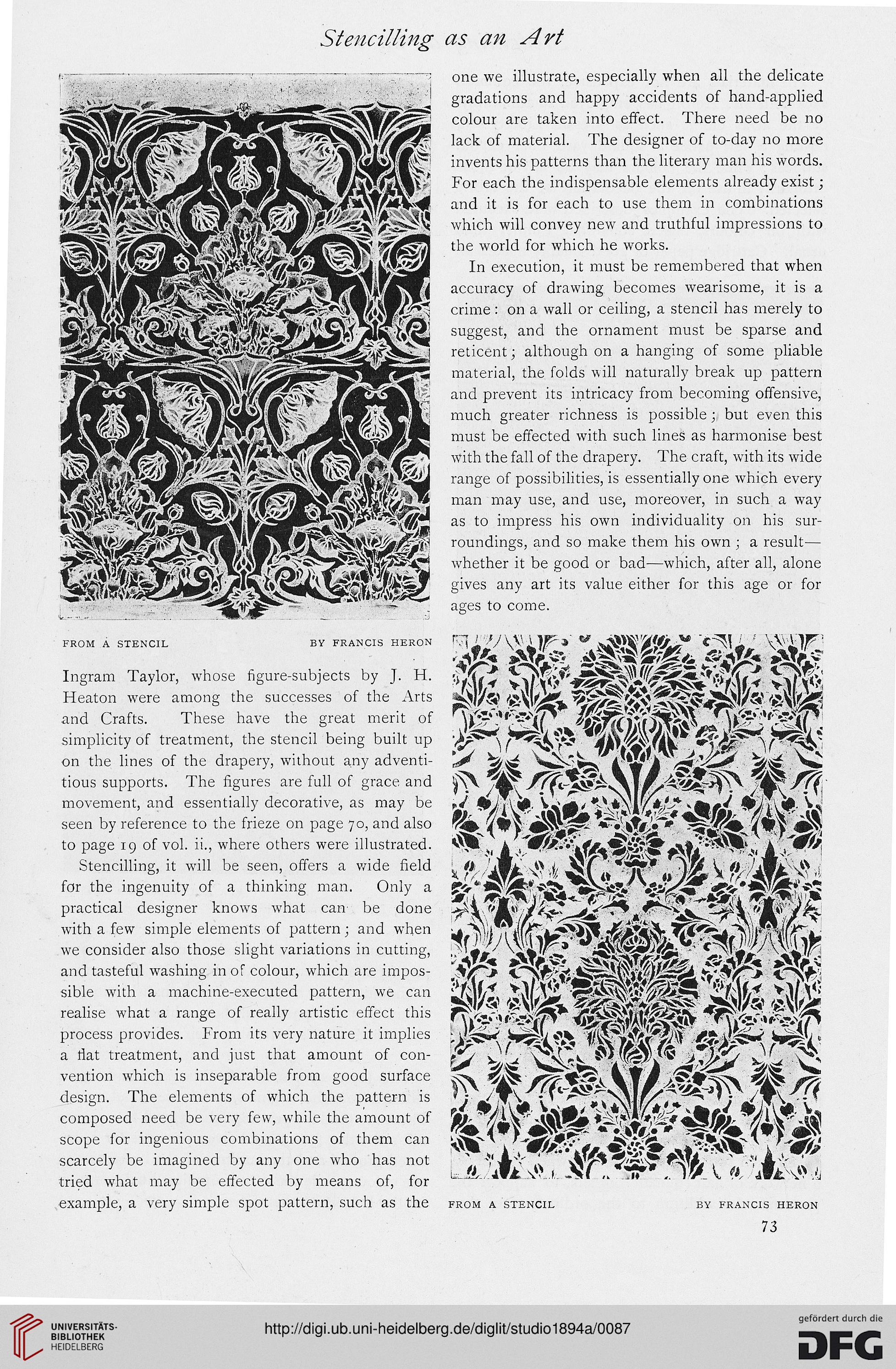

FROM A STENCIL BY FRANCIS HERON

Ingram Taylor, whose figure-subjects by J. H.

Heaton were among the successes of the Arts

and Crafts. These have the great merit of

simplicity of treatment, the stencil being built up

on the lines of the drapery, without any adventi-

tious supports. The figures are full of grace and

movement, and essentially decorative, as may be

seen by reference to the frieze on page 70, and also

to page 19 of vol. ii., where others were illustrated.

Stencilling, it will be seen, offers a wide field

for the ingenuity of a thinking man. Only a

practical designer knows what can be done

with a few simple elements of pattern; and when

we consider also those slight variations in cutting,

and tasteful washing in of colour, which are impos-

sible with a machine-executed pattern, we can

realise what a range of really artistic effect this

process provides. From its very nature it implies

a flat treatment, and just that amount of con-

vention which is inseparable from good surface

design. The elements of which the pattern is

composed need be very few, while the amount of

scope for ingenious combinations of them can

scarcely be imagined by any one who has not

tried what may be effected by means of, for

example, a very simple spot pattern, such as the

as an Art

one we illustrate, especially when all the delicate

gradations and happy accidents of hand-applied

colour are taken into effect. There need be no

lack of material. The designer of to-day no more

invents his patterns than the literary man his words.

For each the indispensable elements already exist;

and it is for each to use them in combinations

which will convey new and truthful impressions to

the world for which he works.

In execution, it must be remembered that when

accuracy of drawing becomes wearisome, it is a

crime : on a wall or ceiling, a stencil has merely to

suggest, and the ornament must be sparse and

reticent; although on a hanging of some pliable

material, the folds will naturally break up pattern

and prevent its intricacy from becoming offensive,

much greater richness is possible ; but even this

must be effected with such lines as harmonise best

with the fall of the drapery. The craft, with its wide

range of possibilities, is essentially one which every

man may use, and use, moreover, in such a way

as to impress his own individuality on his sur-

roundings, and so make them his own ; a result—

whether it be good or bad—which, after all, alone

gives any art its value either for this age or for

ages to come.

FROM A STENCIL BY FRANCIS HERON

Ingram Taylor, whose figure-subjects by J. H.

Heaton were among the successes of the Arts

and Crafts. These have the great merit of

simplicity of treatment, the stencil being built up

on the lines of the drapery, without any adventi-

tious supports. The figures are full of grace and

movement, and essentially decorative, as may be

seen by reference to the frieze on page 70, and also

to page 19 of vol. ii., where others were illustrated.

Stencilling, it will be seen, offers a wide field

for the ingenuity of a thinking man. Only a

practical designer knows what can be done

with a few simple elements of pattern; and when

we consider also those slight variations in cutting,

and tasteful washing in of colour, which are impos-

sible with a machine-executed pattern, we can

realise what a range of really artistic effect this

process provides. From its very nature it implies

a flat treatment, and just that amount of con-

vention which is inseparable from good surface

design. The elements of which the pattern is

composed need be very few, while the amount of

scope for ingenious combinations of them can

scarcely be imagined by any one who has not

tried what may be effected by means of, for

example, a very simple spot pattern, such as the

as an Art

one we illustrate, especially when all the delicate

gradations and happy accidents of hand-applied

colour are taken into effect. There need be no

lack of material. The designer of to-day no more

invents his patterns than the literary man his words.

For each the indispensable elements already exist;

and it is for each to use them in combinations

which will convey new and truthful impressions to

the world for which he works.

In execution, it must be remembered that when

accuracy of drawing becomes wearisome, it is a

crime : on a wall or ceiling, a stencil has merely to

suggest, and the ornament must be sparse and

reticent; although on a hanging of some pliable

material, the folds will naturally break up pattern

and prevent its intricacy from becoming offensive,

much greater richness is possible ; but even this

must be effected with such lines as harmonise best

with the fall of the drapery. The craft, with its wide

range of possibilities, is essentially one which every

man may use, and use, moreover, in such a way

as to impress his own individuality on his sur-

roundings, and so make them his own ; a result—

whether it be good or bad—which, after all, alone

gives any art its value either for this age or for

ages to come.