Country and Suburban Houses

feature of the plan is the care with which children's

and servants' quarters are cut off from the other

part of the house.

In Mr. Rickard's house at Windermere (page

159) we have an ideal bachelor's country quarters,

the plan so arranged that all the service of the

house can be comfortably carried on, access gained

to store cupboard, and so on, without infringing on

the bachelor's private domain.

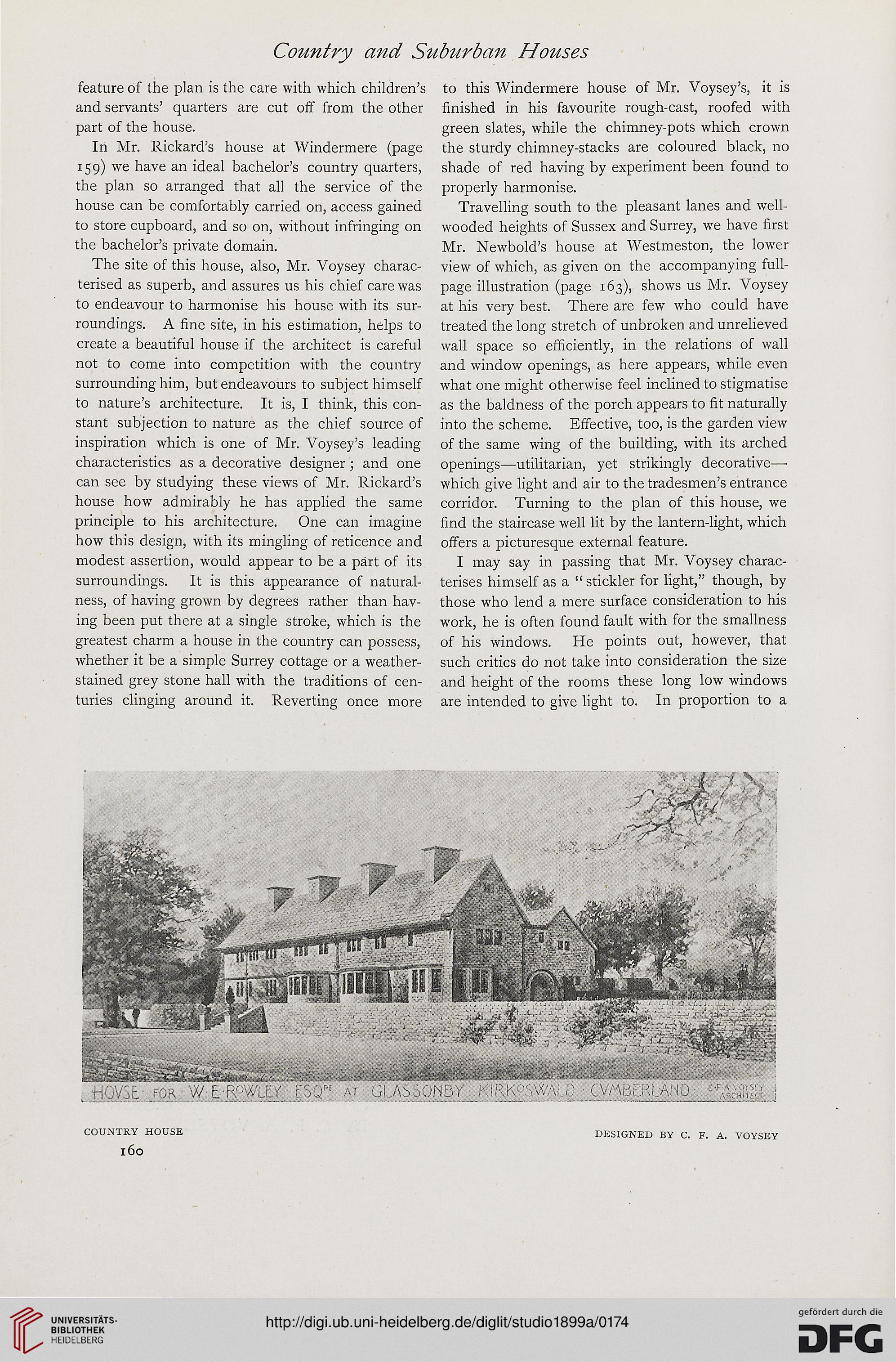

The site of this house, also, Mr. Voysey charac-

terised as superb, and assures us his chief care was

to endeavour to harmonise his house with its sur-

roundings. A fine site, in his estimation, helps to

create a beautiful house if the architect is careful

not to come into competition with the country

surrounding him, but endeavours to subject himself

to nature's architecture. It is, I think, this con-

stant subjection to nature as the chief source of

inspiration which is one of Mr. Voysey's leading

characteristics as a decorative designer; and one

can see by studying these views of Mr. Rickard's

house how admirably he has applied the same

principle to his architecture. One can imagine

how this design, with its mingling of reticence and

modest assertion, would appear to be a part of its

surroundings. It is this appearance of natural-

ness, of having grown by degrees rather than hav-

ing been put there at a single stroke, which is the

greatest charm a house in the country can possess,

whether it be a simple Surrey cottage or a weather-

stained grey stone hall with the traditions of cen-

turies clinging around it. Reverting once more

to this Windermere house of Mr. Voysey's, it is

finished in his favourite rough-cast, roofed with

green slates, while the chimney-pots which crown

the sturdy chimney-stacks are coloured black, no

shade of red having by experiment been found to

properly harmonise.

Travelling south to the pleasant lanes and well-

wooded heights of Sussex and Surrey, we have first

Mr. Newbold's house at Westmeston, the lower

view of which, as given on the accompanying full-

page illustration (page 163), shows us Mr. Voysey

at his very best. There are few who could have

treated the long stretch of unbroken and unrelieved

wall space so efficiently, in the relations of wall

and window openings, as here appears, while even

what one might otherwise feel inclined to stigmatise

as the baldness of the porch appears to fit naturally

into the scheme. Effective, too, is the garden view

of the same wing of the building, with its arched

openings—utilitarian, yet strikingly decorative—

which give light and air to the tradesmen's entrance

corridor. Turning to the plan of this house, we

find the staircase well lit by the lantern-light, which

offers a picturesque external feature.

I may say in passing that Mr. Voysey charac-

terises himself as a " stickler for light," though, by

those who lend a mere surface consideration to his

work, he is often found fault with for the smallness

of his windows. He points out, however, that

such critics do not take into consideration the size

and height of the rooms these long low windows

are intended to give light to. In proportion to a

COUNTRY HOUSE

160

DESIGNED BY C. F. A. VOYSEY

feature of the plan is the care with which children's

and servants' quarters are cut off from the other

part of the house.

In Mr. Rickard's house at Windermere (page

159) we have an ideal bachelor's country quarters,

the plan so arranged that all the service of the

house can be comfortably carried on, access gained

to store cupboard, and so on, without infringing on

the bachelor's private domain.

The site of this house, also, Mr. Voysey charac-

terised as superb, and assures us his chief care was

to endeavour to harmonise his house with its sur-

roundings. A fine site, in his estimation, helps to

create a beautiful house if the architect is careful

not to come into competition with the country

surrounding him, but endeavours to subject himself

to nature's architecture. It is, I think, this con-

stant subjection to nature as the chief source of

inspiration which is one of Mr. Voysey's leading

characteristics as a decorative designer; and one

can see by studying these views of Mr. Rickard's

house how admirably he has applied the same

principle to his architecture. One can imagine

how this design, with its mingling of reticence and

modest assertion, would appear to be a part of its

surroundings. It is this appearance of natural-

ness, of having grown by degrees rather than hav-

ing been put there at a single stroke, which is the

greatest charm a house in the country can possess,

whether it be a simple Surrey cottage or a weather-

stained grey stone hall with the traditions of cen-

turies clinging around it. Reverting once more

to this Windermere house of Mr. Voysey's, it is

finished in his favourite rough-cast, roofed with

green slates, while the chimney-pots which crown

the sturdy chimney-stacks are coloured black, no

shade of red having by experiment been found to

properly harmonise.

Travelling south to the pleasant lanes and well-

wooded heights of Sussex and Surrey, we have first

Mr. Newbold's house at Westmeston, the lower

view of which, as given on the accompanying full-

page illustration (page 163), shows us Mr. Voysey

at his very best. There are few who could have

treated the long stretch of unbroken and unrelieved

wall space so efficiently, in the relations of wall

and window openings, as here appears, while even

what one might otherwise feel inclined to stigmatise

as the baldness of the porch appears to fit naturally

into the scheme. Effective, too, is the garden view

of the same wing of the building, with its arched

openings—utilitarian, yet strikingly decorative—

which give light and air to the tradesmen's entrance

corridor. Turning to the plan of this house, we

find the staircase well lit by the lantern-light, which

offers a picturesque external feature.

I may say in passing that Mr. Voysey charac-

terises himself as a " stickler for light," though, by

those who lend a mere surface consideration to his

work, he is often found fault with for the smallness

of his windows. He points out, however, that

such critics do not take into consideration the size

and height of the rooms these long low windows

are intended to give light to. In proportion to a

COUNTRY HOUSE

160

DESIGNED BY C. F. A. VOYSEY