English Drawing

changeless in character, to become personal and

wayward. It becomes this in a fascinating degree

when we look for individuality, recognising as draw-

ing, t°°! the very quality of the touch with which

pencil is put to paper. We know that the artist’s is

an educated vision, that he has extended the boun-

daries of normal vision, that his art changes for him

the appearance of life before he can change life back

into his art; nature seldom looks as if she were

drawn in grey pencil, but in grey pencil any mood

of nature can be translated. There is a school of

drawing which is chiefly concerned with and aims

at the vivid realisation of an idea or object for the

sake of the object or the idea associated with it,

and another school which finds its pleasure simply

in actual drawing itself for the sake of drawing.

The artist of the first would be attracted towards

the rendering of some beautiful drapery or costume,

some charm of a face; the latter would be drawn

towards his subject by some happy conjunction of

lines which could be artistically rendered. The

first school is the preparatory one to the second,

which comes to the principle of pure art unrelated

to its subject; rendering a

beauty which is quite as

likely to be found in an

ugly subject as in a beauti-

ful one, using the word ugly

in its conventional sense.

Their recognition of the

independence of beauty to

subject makes for the finest

art. A fine artist cannot

escape beauty, it lurks for

him everywhere, born out

of his own vision ; every-

where accident arranges it

for him with a charmed

fatality. His dreams have

a counterpart in the actual

world that is so disappoint-

ing to many of us. It

requires a great artistic per-

ception, perhaps, this con-

sciousness that life cannot

escape beauty if it would,

that everywhere about our

feet the net of beauty is

laid. The supreme artist

may touch any part of life

and find it inspiring, whilst

others settle with bent

brows to thrash the beauty

out of a sunset or rescue

at Leighton Llouse

a reminiscence of beauty from old - fashioned

subjects.

Drawing was the primary artistic instinct in man;

as an afterthought came the embellishment of

colour. It would now almost seem as if colour

was made the first aim, and as an afterthought

sometimes comes the embellishment of drawing.

Recognising that art has always been impression-

istic, concerned with the appearance of things

and indirectly only with their actual construction,

if the artist wishes to get actual representa-

tion of an object and not only a rendering of

colour, he will invite drawing into his picture—he

will entertain it, if even as an angel unawares.

There is no drawing in tone or shadow as such,

any more than there is in colour. A square piece

of tone cut out of a shadow means nothing, whilst

a beautiful square of colour means something in

itself. Colour, unlike drawing, has an existence

unrelated to the fact which it expresses in the

painting. And, too, whilst the colour of a thing is

caused and varied by light, its form, buried in these

changing phenomena, is a secret unalterable; though

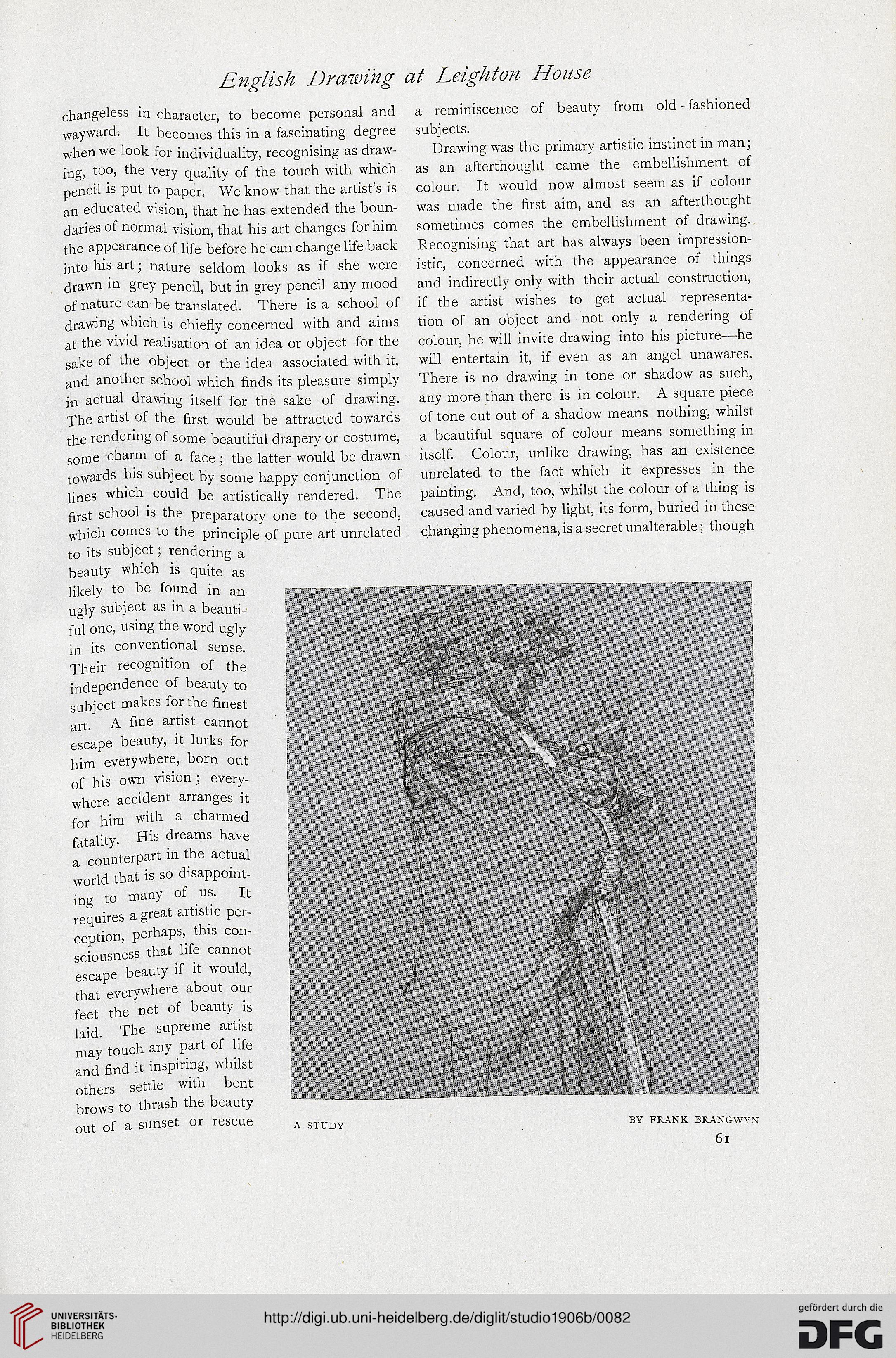

A STUDY

BY FRANK BRANGWYN

61

changeless in character, to become personal and

wayward. It becomes this in a fascinating degree

when we look for individuality, recognising as draw-

ing, t°°! the very quality of the touch with which

pencil is put to paper. We know that the artist’s is

an educated vision, that he has extended the boun-

daries of normal vision, that his art changes for him

the appearance of life before he can change life back

into his art; nature seldom looks as if she were

drawn in grey pencil, but in grey pencil any mood

of nature can be translated. There is a school of

drawing which is chiefly concerned with and aims

at the vivid realisation of an idea or object for the

sake of the object or the idea associated with it,

and another school which finds its pleasure simply

in actual drawing itself for the sake of drawing.

The artist of the first would be attracted towards

the rendering of some beautiful drapery or costume,

some charm of a face; the latter would be drawn

towards his subject by some happy conjunction of

lines which could be artistically rendered. The

first school is the preparatory one to the second,

which comes to the principle of pure art unrelated

to its subject; rendering a

beauty which is quite as

likely to be found in an

ugly subject as in a beauti-

ful one, using the word ugly

in its conventional sense.

Their recognition of the

independence of beauty to

subject makes for the finest

art. A fine artist cannot

escape beauty, it lurks for

him everywhere, born out

of his own vision ; every-

where accident arranges it

for him with a charmed

fatality. His dreams have

a counterpart in the actual

world that is so disappoint-

ing to many of us. It

requires a great artistic per-

ception, perhaps, this con-

sciousness that life cannot

escape beauty if it would,

that everywhere about our

feet the net of beauty is

laid. The supreme artist

may touch any part of life

and find it inspiring, whilst

others settle with bent

brows to thrash the beauty

out of a sunset or rescue

at Leighton Llouse

a reminiscence of beauty from old - fashioned

subjects.

Drawing was the primary artistic instinct in man;

as an afterthought came the embellishment of

colour. It would now almost seem as if colour

was made the first aim, and as an afterthought

sometimes comes the embellishment of drawing.

Recognising that art has always been impression-

istic, concerned with the appearance of things

and indirectly only with their actual construction,

if the artist wishes to get actual representa-

tion of an object and not only a rendering of

colour, he will invite drawing into his picture—he

will entertain it, if even as an angel unawares.

There is no drawing in tone or shadow as such,

any more than there is in colour. A square piece

of tone cut out of a shadow means nothing, whilst

a beautiful square of colour means something in

itself. Colour, unlike drawing, has an existence

unrelated to the fact which it expresses in the

painting. And, too, whilst the colour of a thing is

caused and varied by light, its form, buried in these

changing phenomena, is a secret unalterable; though

A STUDY

BY FRANK BRANGWYN

61