THEOPHILE ALEXANDRE STEINLEN

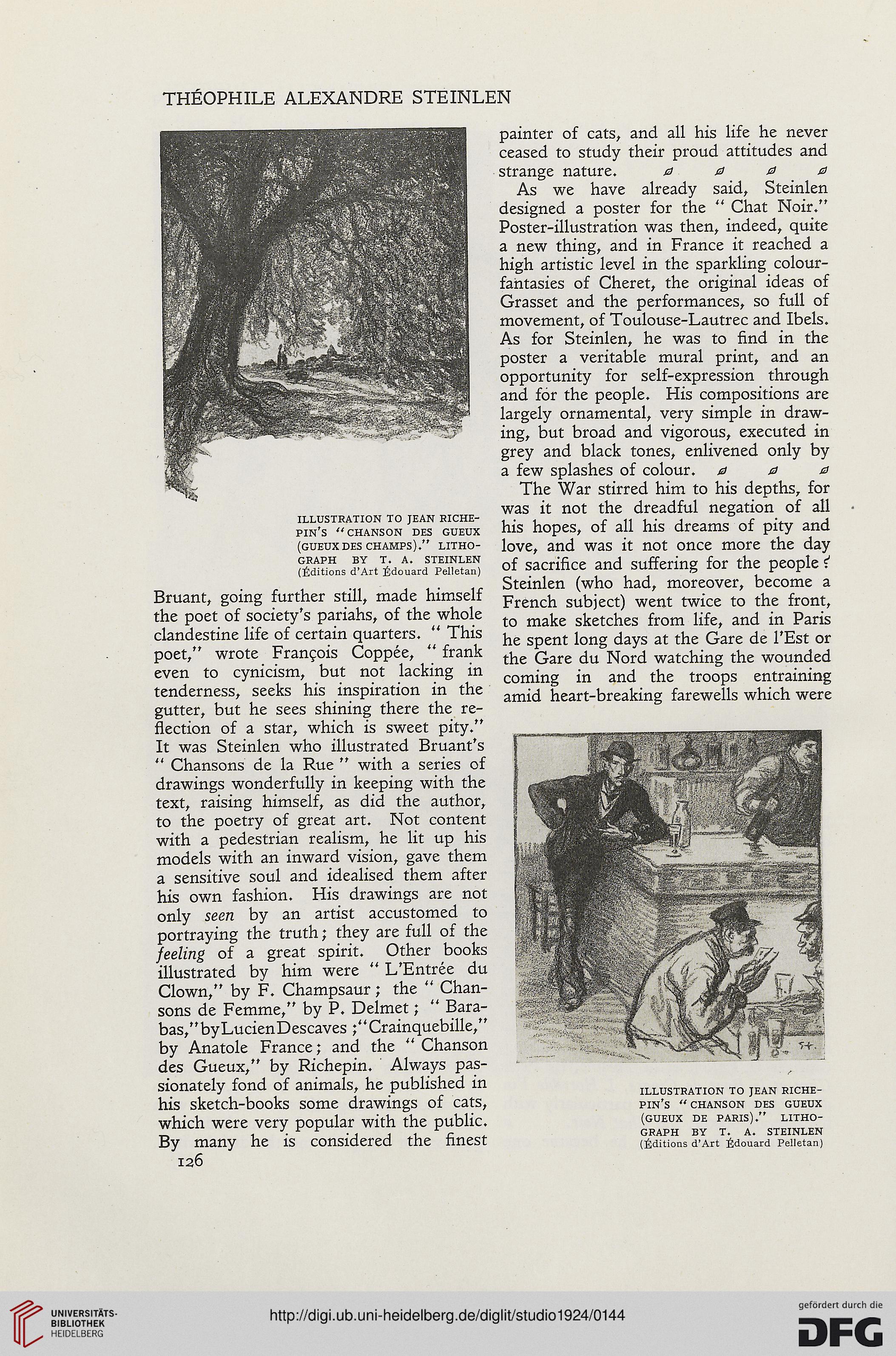

ILLUSTRATION TO JEAN RICHE-

PIN'S "CHANSON DES GUEUX

(gueuxdes champs)/* litho-

graph BY T. A. STEINLEN

(Editions d’Art J^douard Pelletan)

Bruant, going further still, made himself

the poet of society’s pariahs, of the whole

clandestine life of certain quarters. “ This

poet,” wrote Francois Coppee, “ frank

even to cynicism, but not lacking in

tenderness, seeks his inspiration in the

gutter, but he sees shining there the re-

flection of a star, which is sweet pity.”

It was Steinlen who illustrated Bruant’s

“ Chansons de la Rue ” with a series of

drawings wonderfully in keeping with the

text, raising himself, as did the author,

to the poetry of great art. Not content

with a pedestrian realism, he lit up his

models with an inward vision, gave them

a sensitive soul and idealised them after

his own fashion. His drawings are not

only seen by an artist accustomed to

portraying the truth; they are full of the

feeling of a great spirit. Other books

illustrated by him were “ L’Entree du

Clown,” by F. Champsaur; the “ Chan-

sons de Femme,” by P. Delmet; “ Bara-

bas,”byLucienDescaves ;“Crainquebille,”

by Anatole France; and the “ Chanson

des Gueux,” by Richepin. Always pas-

sionately fond of animals, he published in

his sketch-books some drawings of cats,

which were very popular with the public.

By many he is considered the finest

126

painter of cats, and all his life he never

ceased to study their proud attitudes and

strange nature. 0000

As we have already said, Steinlen

designed a poster for the “ Chat Noir.”

Poster-illustration was then, indeed, quite

a new thing, and in France it reached a

high artistic level in the sparkling colour-

fantasies of Cheret, the original ideas of

Grasset and the performances, so full of

movement, of Toulouse-Lautrec and Ibels.

As for Steinlen, he was to find in the

poster a veritable mural print, and an

opportunity for self-expression through

and for the people. His compositions are

largely ornamental, very simple in draw-

ing, but broad and vigorous, executed in

grey and black tones, enlivened only by

a few splashes of colour. 000

The War stirred him to his depths, for

was it not the dreadful negation of all

his hopes, of all his dreams of pity and

love, and was it not once more the day

of sacrifice and suffering for the people i

Steinlen (who had, moreover, become a

French subject) went twice to the front,

to make sketches from life, and in Paris

he spent long days at the Gare de l’Est or

the Gare du Nord watching the wounded

coming in and the troops entraining

amid heart-breaking farewells which were

ILLUSTRATION TO JEAN RICHE-

PIN’S “ CHANSON DES GUEUX

(GUEUX DE PARIS).” LITHO-

GRAPH BY T. A. STEINLEN

(Editions d’Art Edouard Pelletan)

ILLUSTRATION TO JEAN RICHE-

PIN'S "CHANSON DES GUEUX

(gueuxdes champs)/* litho-

graph BY T. A. STEINLEN

(Editions d’Art J^douard Pelletan)

Bruant, going further still, made himself

the poet of society’s pariahs, of the whole

clandestine life of certain quarters. “ This

poet,” wrote Francois Coppee, “ frank

even to cynicism, but not lacking in

tenderness, seeks his inspiration in the

gutter, but he sees shining there the re-

flection of a star, which is sweet pity.”

It was Steinlen who illustrated Bruant’s

“ Chansons de la Rue ” with a series of

drawings wonderfully in keeping with the

text, raising himself, as did the author,

to the poetry of great art. Not content

with a pedestrian realism, he lit up his

models with an inward vision, gave them

a sensitive soul and idealised them after

his own fashion. His drawings are not

only seen by an artist accustomed to

portraying the truth; they are full of the

feeling of a great spirit. Other books

illustrated by him were “ L’Entree du

Clown,” by F. Champsaur; the “ Chan-

sons de Femme,” by P. Delmet; “ Bara-

bas,”byLucienDescaves ;“Crainquebille,”

by Anatole France; and the “ Chanson

des Gueux,” by Richepin. Always pas-

sionately fond of animals, he published in

his sketch-books some drawings of cats,

which were very popular with the public.

By many he is considered the finest

126

painter of cats, and all his life he never

ceased to study their proud attitudes and

strange nature. 0000

As we have already said, Steinlen

designed a poster for the “ Chat Noir.”

Poster-illustration was then, indeed, quite

a new thing, and in France it reached a

high artistic level in the sparkling colour-

fantasies of Cheret, the original ideas of

Grasset and the performances, so full of

movement, of Toulouse-Lautrec and Ibels.

As for Steinlen, he was to find in the

poster a veritable mural print, and an

opportunity for self-expression through

and for the people. His compositions are

largely ornamental, very simple in draw-

ing, but broad and vigorous, executed in

grey and black tones, enlivened only by

a few splashes of colour. 000

The War stirred him to his depths, for

was it not the dreadful negation of all

his hopes, of all his dreams of pity and

love, and was it not once more the day

of sacrifice and suffering for the people i

Steinlen (who had, moreover, become a

French subject) went twice to the front,

to make sketches from life, and in Paris

he spent long days at the Gare de l’Est or

the Gare du Nord watching the wounded

coming in and the troops entraining

amid heart-breaking farewells which were

ILLUSTRATION TO JEAN RICHE-

PIN’S “ CHANSON DES GUEUX

(GUEUX DE PARIS).” LITHO-

GRAPH BY T. A. STEINLEN

(Editions d’Art Edouard Pelletan)