The Illustrated Catalogs – digital edition

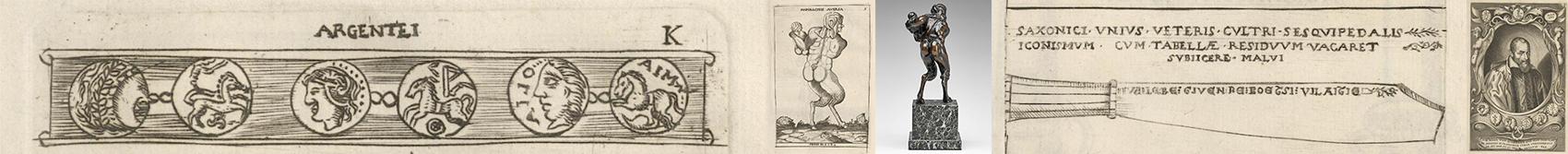

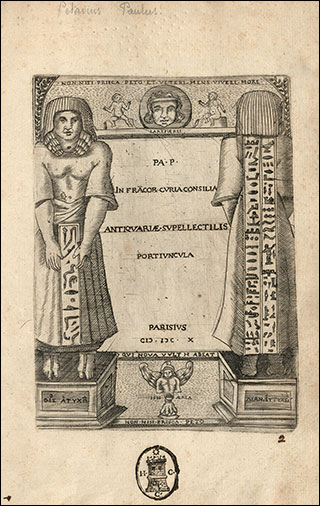

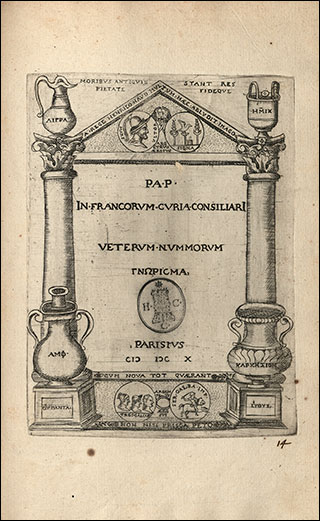

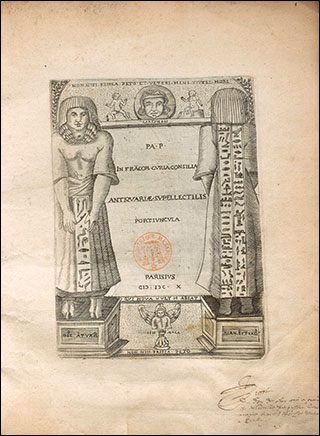

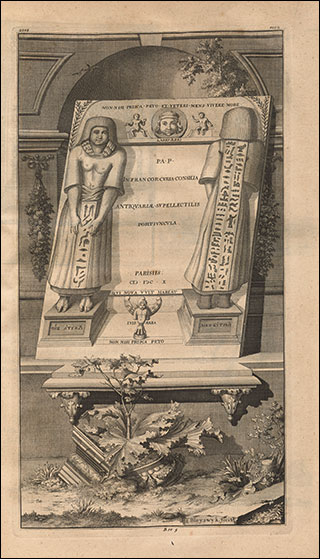

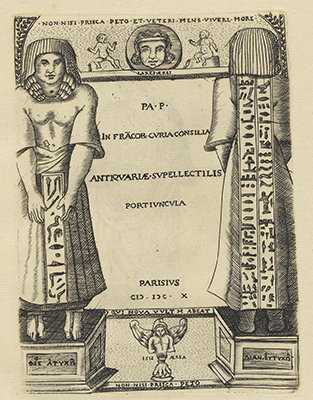

In 1610 Paul Petau published an illustrated catalog of his collection of antiquities, which represents a turning point in the history of antiquarian culture. The book is made of two parts, the Antiquariae Supellectilis Portiuncula (prints of small objects) and the Veterum Nummorum Gnōrisma (prints of Roman and early medieval coins); there is no commentary, just captions and short notes on the illustrations. This work represents the first printed illustrated catalog of a private collection of ancient objects known so far of which in the 18th century there were other editions, the most important one is that of 1757. The annotated online edition of the different version(s) of Petau’s illustrated catalog of his collection links the images to the extant objects, mainly preserved in Paris.

Since the books are self-published, there are copies of the two volumes (especially the Portiuncula) with a different number of plates; probably, new prints were made around 1612–13, so that copies of the book may vary in the number and sequence of pages. Furthermore, the presence of the author's portrait is inconsistent. As the list of specimens shows, the 1610 volumes we consulted have a number of plates ranging from a minimum of 31 to a maximum of 50. That is why it is relevant to have an annotated online edition of the first version(s) of Petau’s catalog. Furthermore, it could be compared with the subsequent editions of 1718, 1735, and 1757, to understand why, almost a century and a half after the first edition, the scholarly community looked at Petau’s work with renewed interest after it had not noticed it for a long time. A first impact can be seen in Bernard de Montfaucon’s work who, while not embracing all of Petau’s legacy, gave him a prominent place in his L’Antiquitée expliquée et représentée en figures (1719–1724) and particularly in Les Monumens De La Monarchie Françoise (1729–1733).