Objects

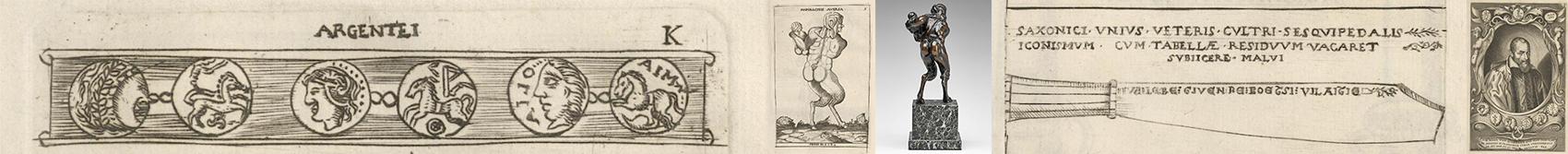

Petau collected multiple antiquities (Egyptian, Roman, medieval) and also some modern objects (whether they were considered ancient or not). Furthermore, the second volume, Veterum Nummorum Gnōrisma, is one of the first attempts to publish images, however poor, of ancient French coins, of which Petau was acknowledged to be one of the very first collectors. The number of pieces owned by Petau is quite small: the original edition of the two-volume catalog Portiuncula and Gnōrisma (1610) shows about 250 objects—50 antiquities and 200 coins. More pieces are published in 18th-century editions, so that the final number of antiquities reaches over 400 items—about 80 ancient objects and 350 coins.

Among the antiquities represented in the first volume, there are also pieces known by Petau, but not in his possession; other objects were copied after other books of drawings (especially belonging to the tradition of the work by Pirro Ligorio) or manuscripts, probably preserved in the library. Petau also gives a ‘pioneering’ illustrated account of recent archaeological discoveries as shown by the depiction of two skeletons with their grave goods (found 1612) and an altar dedicated to Mercury and Rosmerta (found 1615), probably added later by his son Alexandre. Petau’s collection included some modern objects interpreted as classical (such as a Renaissance lamp with the sacrifice to Priapus, or a modern medal by Lysippus). A certain number of the pieces actually owned by Petau can now be traced in Paris, at the Cabinet des Médailles, of which they represent some of the most ancient acquisitions.

A significant novelty brought about in his second volume, Veterum Nummorum Gnōrisma, is the interest in Gallic and Medieval coins, especially Carolingian and Merovingian. This collection deserves particular attention and investigation, since it can be rightly considered one of the first attempts to publish images, however poor, of ancient French coins. One could assume that Petau gave momentum to the study of Gallic/Celtic and Medieval coins, echoed for instance in Claude Bouterouë’s work on his curious research on French coins (Bouteroüe 1666) and that the book may also have played a role in Montfaucon’s fourth volume of his L'Antiquité expliquée (1719) (Montfaucon 1719, II, 2, p. 418–33) or in Maffei’s Galliae antiquitates (1733). In modern times Adrien Blanchet, in his seminal treaty (1905) on Gallic coins, stresses Paul Petau’s role in initiating interest in Medieval coins pointing him out as “one of the first who took some interest in Gallic coins and he had a certain number of them engraved, chosen from his collection” (Blanchet 1905, p.1–2). The greatest part of Petau’s collection of coins came into Nicolas Fabri de Peiresc’s possession and it is possible to recognize some of the pieces in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris.

Antiquities Antiquariae Supellectilis Portiuncula- Statues and Statuettes

- Oil lamps

- Gravestones

- Vases

- Inscriptions

- Object of the Material Culture

- Worship Objects

- Archaeological finds

- other

- Roman

- Gallic

- Merovingian

- Carolingian

- other