Paul Petau Digital: Collection and Catalog, Antiquities and Manuscripts

What are Petau’s motivations for collecting antiquities and publishing the catalog of his museum? To whom was it addressed? Is it only a matter of curiosity? Moreover, what is the source of his interest in medieval coins, almost unprecedented in the culture of his time? The hypothesis proposed here is that studying the past for Petau meant going back to the origin of the unity between political and religious power. 1610 (listed as the year of publication) is not a mere chronological coincidence while the recurring phrase—Non nisi prisca peto—is, besides an erudite motto, more importantly a programmatic political statement.

Thanks to the generous funding from Thyssen Stiftung, its location in the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte—one of the major research institutes in Germany—and the technical infrastructure of the Heidelberg University Library for sustainable data storage, citable publication, long-term archiving, and broad dissemination of the results, the project will provide a critical assessment of Paul Petau’s role in early 17th-century European culture while entailing two deliverables:

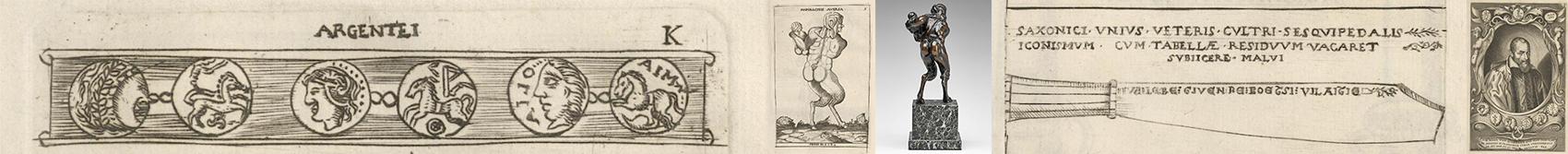

an online annotated critical edition of the first printed illustrated two-volume catalog of antiquities Portiuncula and Gnōrisma (1757 edition), including:

- the digital facsimiles of the various catalog editions between 1610 and 1757

- a) the so called “edition minor” of the Antiquariae supellectilis portiuncula and Veterum Nummorum Gnōrisma, Parisius 1610 with 31 plates (Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense Rome: Sign. M.XI.26)

- b) the so called “edition maior” of the Antiquariae supellectilis portiuncula and Veterum Nummorum Gnōrisma, Parisius 1618 with 50 plates (Paris, BnF, Sign. 8 RES IMP-375)

- c) the 1718 edition (Pauli Petavii In Francorum Curia Consiliarii Antiquariae Suppellectilis Portiuncula: nec non eiusdem vetervum nummorum ΓΝΩΡΙCMA in: Albert-Henri de Sallengre: Novus thesaurus antiquitatum Romanarum…, Hagae Comitum 1716-1719, 3 vols.; II, 1718, coll. 997–1050)

- d) the 1746 edition (Pauli Petavii In Francorum Curia Consiliarii Antiquariae Suppellectilis Portiuncula in: Cuper, Gisbert: De Elephantis In Nummis Obviis Exercitationes Duæ, Den Haag, Hondt, 1746, coll. 1001–1050

- e) the 1757 edition (Explication de plusieurs antiquités recueillies par Paul Petau, conseiller au parlement de Paris, Amsterdam 1757) with annotations and commentary

- the database-supported identification and in-depth indexing of the objects published there (antiquities and coins)

- an interactive and dynamically expandable commentary apparatus

an Open Access publication on life, work and impact of Petau in European culture including:

- the first biography of Paul Petau based on his status and effect within the Republic of Letters, taking into account his political activity, his sphere of action and his contacts

- the virtual reconstruction of his manuscripts and books collection through the transcription of the inventories (individual entries will eventually be linkable with the catalog entries of the libraries where the volumes are now)

- Petau’s role within the history of collecting and the tradition of antiquarian studies through the analysis of the data emerged from the online annotated edition

- the result of a study day

The examination of these closely related aspects will do justice to a figure long underestimated, but of exceptional importance to understand the beginnings of antiquarian interests from the 17th century onward in both France and Europe. The two intended deliverables will contextualize Petau’s cultural activity in 17th-century France: as collector, scholar, editor and statesman in a period of deep cultural changes and religious conflicts. While placing the figure of Paul Petau in the context of the antiquarian world at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries it will be also possible to explore the link between antiquarian research, national history and religious history studies also considering two other publications by him: De Epocha annorum incarnationis Christi (1604) and De Nithardo, Caroli Magni nepote (1613). Petau sees the past as a continuum which, starting from the greatness of ancient emperors, leads to the early kings of France. As for the leaders of the past, in France religion and kingdom were closely linked to each other. The thesis outlined here is that Petau’s work is meant to reinforce this connection between Catholic faith and the Crown, threatened by the Reformation.

Theories and methods

While manageable in size, Petau’s collection poses a series of challenges regarding the different categories of objects, the eligibility criteria, their authenticity, the taxonomy order both in their display within the collection and in the printed publication, and, last but not least, the choice on how to represent and document the pieces. In order to coherently consider all these aspects for the research perspective, a multifaceted approach is required, therefore the following methodological criteria will be applied in the project:

- Basic research of visual and written sources

Artifacts in museums and collections will be traced by rectifying some misinterpretations and identifying the presence of modern objects alongside ancient ones that have been reproduced without any indication (i.e. as if they were ancient), such as the Louvre statuette of a female satyr mentioned above (fig. 3a). This will be instrumental in explaining that Petau as well as others primarily intended to retrieve the ‘national/local’ past by contradicting the idea of classicism. In fact, for many (even Pignoria for example) collecting and studying antiquities were more a search for origins than for models and it is in the late classical and in the Mediaeval periods that many answers could be found. - Taxonomy: knowledge organization / order structure

This methodological approach will help clarify the constitution and purpose of Petau’s collection. Is there a system and, if so, which one? How does Petau organize his knowledge: by categories—and this only with regard to a collection exclusively of artificialia—, chronologically, topographically, according to the space available, or otherwise? Does an internal order exist and, if so, does it correspond to the external visualization (printed volumes)?27 Considering that his messages rely only on pictures as there are neither comments nor explanatory text, does a dialectical relationship exist between the two moments—collection and manifestation (Inszenierung)— and, if so, what is it? Is there continuity (persistence) or instead change (transformation) from the creation of the collection and the pictorial mediality? - Collection research and theory / object biography

Starting with the awareness that Petau did not make a big difference between antique and Mediaeval artifacts, cult objects and material culture, it will be useful to clarify Petau’s strategies related to collecting, display (private museum) and representation (publications). Assuming that collection practices are understood as part of early modern social-historical and thus political relations, how should Petau’s museum and the two printed volumes with corresponding representation of his collection be classified? Are they a mirror of political-religious ideals that coexist with antiquarian-historical interests? And how should we place the library in this context? - Image-science / theory of visual culture (Bildwissenschaft):

Petau’s two volumes of his collection of antiquities and coins are undoubtedly laden with images. Does he consider the images a justification of a visual culture (images as vehicles of knowledge)? Are they used as ‘agents’ and, if so, is that the reason—i.e. the medial impact of the images—why he has not provided a text?