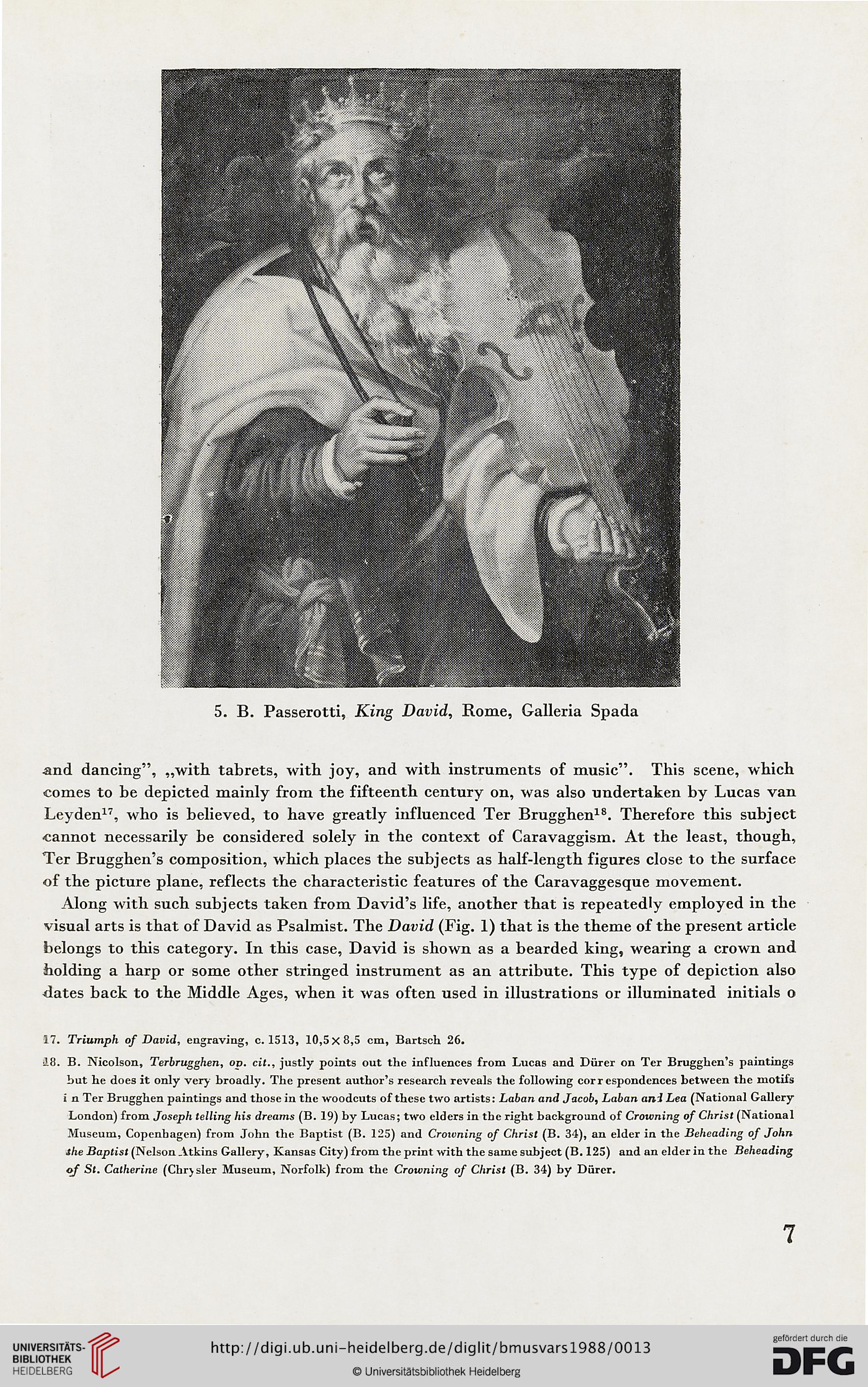

5. B. Passerotti, King David, Romę, Galleria Spada

and dancing", „with tabrets, with joy, and with instruments of musie". This scenę, which

comes to be depicted mainly from the fifteenth century on, was also undertaken by Lucas van

Leyden17, wbo is believed, to have greatly influenced Ter Brugghen18. Therefore this subject

-cannot necessarily be considered solely in the context of Caravaggism. At the least, though,

Ter Brugghen's composition, which places the subjects as half-lcngth figures close to the surface

of the picture piane, reflects the characteristic features of the Caravaggesque movement.

Along with such subjects taken from David's life, another that is repeatedly employed in the

visual arts is that of David as Psalmist. The David (Fig. 1) that is the theme of the present article

belongs to this category. In this case, David is shown as a bearded king, wearing a crown and

holding a harp or some other stringed instrument as an attribute. This type of depiction also

dates back to the Middle Ages, when it was often used in illustrations or illuminated initials o

17. Triumph of David, engraving, c. 1513, 10,5x8,5 cm, Bartsch 26.

■18. B. Nicolson, Terbrugghen, on. clt., justly points out the influences from Lucas and Dirrer on Ter Brugghcn's paintings

but he does it only very broadly. The present author's research reveals the following correspondences between the motifs

i n Ter Brugghen paintings and those in the woodcuts of these two artists: Laban and Jacob, Laban ani Lea (National Gallery

London) from Joseph telling his dreams (B. 19) by Lucas; two elders in the rigbt baekground of Crouming of Christ (National

Museum, Copcnbagen) from John the Baptist (B. 125) and Crowning of Christ (B. 34), an elder in the Beheading of John

the Baptist (Nelson Atkins Gallery, Kansas City) from the print with the same subject (B. 125) and an elder in the Beheading

of St. Calherine (Chrj sler Museum, Norfolk) from the Crowning of Christ (B. 34) by Diirer.

7

and dancing", „with tabrets, with joy, and with instruments of musie". This scenę, which

comes to be depicted mainly from the fifteenth century on, was also undertaken by Lucas van

Leyden17, wbo is believed, to have greatly influenced Ter Brugghen18. Therefore this subject

-cannot necessarily be considered solely in the context of Caravaggism. At the least, though,

Ter Brugghen's composition, which places the subjects as half-lcngth figures close to the surface

of the picture piane, reflects the characteristic features of the Caravaggesque movement.

Along with such subjects taken from David's life, another that is repeatedly employed in the

visual arts is that of David as Psalmist. The David (Fig. 1) that is the theme of the present article

belongs to this category. In this case, David is shown as a bearded king, wearing a crown and

holding a harp or some other stringed instrument as an attribute. This type of depiction also

dates back to the Middle Ages, when it was often used in illustrations or illuminated initials o

17. Triumph of David, engraving, c. 1513, 10,5x8,5 cm, Bartsch 26.

■18. B. Nicolson, Terbrugghen, on. clt., justly points out the influences from Lucas and Dirrer on Ter Brugghcn's paintings

but he does it only very broadly. The present author's research reveals the following correspondences between the motifs

i n Ter Brugghen paintings and those in the woodcuts of these two artists: Laban and Jacob, Laban ani Lea (National Gallery

London) from Joseph telling his dreams (B. 19) by Lucas; two elders in the rigbt baekground of Crouming of Christ (National

Museum, Copcnbagen) from John the Baptist (B. 125) and Crowning of Christ (B. 34), an elder in the Beheading of John

the Baptist (Nelson Atkins Gallery, Kansas City) from the print with the same subject (B. 125) and an elder in the Beheading

of St. Calherine (Chrj sler Museum, Norfolk) from the Crowning of Christ (B. 34) by Diirer.

7