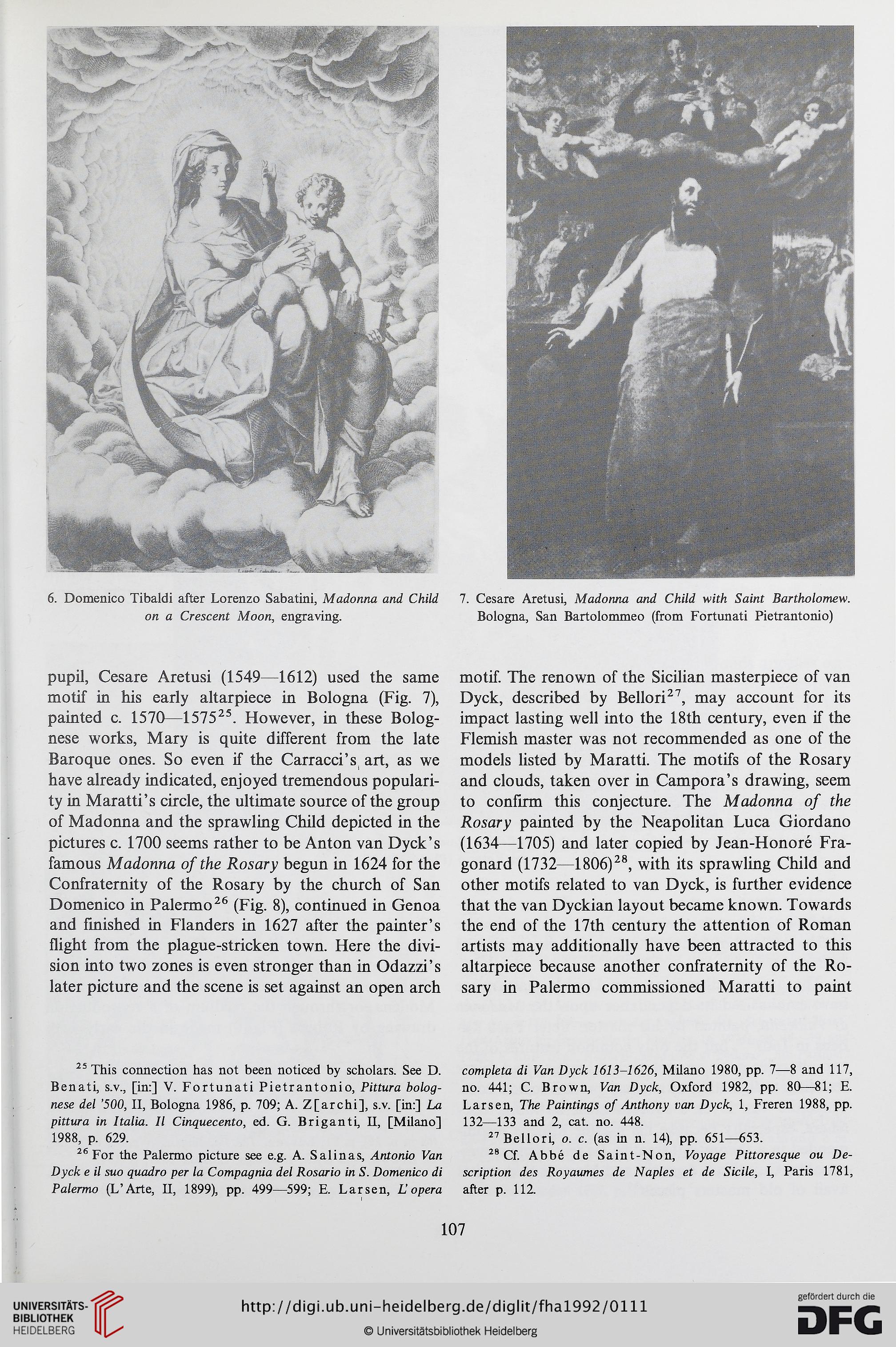

7. Cesare Aretusi, Madonna and Child with Saint Bartholomew.

Bologna, San Bartolommeo (from Fortunati Pietrantonio)

motif. The renown of the Sicilian masterpiece of van

Dyck, described by Bellori27, may account for its

impact lasting well into the 18th century, even if the

Flemish master was not recommended as one of the

models listed by Maratti. The motifs of the Rosary

and clouds, taken over in Campora’s drawing, seem

to confrrm this conjecture. The Madonna of the

Rosary painted by the Neapolitan Luca Giordano

(1634—1705) and later copied by Jean-Honore Fra-

gonard (1732—1806)28, with its sprawling Child and

other motifs related to van Dyck, is further evidence

that the van Dyckian layout became known. Towards

the end of the 17th century the attention of Roman

artists may additionally have been attracted to this

altarpiece because another confraternity of the Ro-

sary in Palermo commissioned Maratti to paint

completa di Van Dyck 1613-1626, Milano 1980, pp. 7—8 and 117,

no. 441; C. Brown, Van Dyck, Oxford 1982, pp. 80—81; E.

Lar sen, The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck, 1, Freren 1988, pp.

132—133 and 2, cat. no. 448.

27 Bellori, o. c. (as in n. 14), pp. 651—653.

28 Cf. Abbe de Saint-Non, Yoyage Pittoresąue ou De-

scription des Royaumes de Naples et de Sicile, L, Paris 1781,

after p. 112.

6. Domenico Tibaldi after Lorenzo Sabatini, Madonna and Child

on a Crescent Moon, engraving.

pupil, Cesare Aretusi (1549—1612) used the same

motif in his early altarpiece in Bologna (Fig. 7),

painted c. 1570—157525. However, in these Bolog-

nese works, Mary is ąuite different from the late

Baroąue ones. So even if the CarraccPs art, as we

have already indicated, enjoyed tremendous populari-

ty in Maratti’s circle, the ultimate source of the group

of Madonna and the sprawling Child depicted in the

pictures c. 1700 seems rather to be Anton van Dyck’s

famous Madonna of the Rosary begun in 1624 for the

Confraternity of the Rosary by the church of San

Domenico in Palermo26 (Fig. 8), continued in Genoa

and finished in Flanders in 1627 after the painter’s

flight from the plague-stricken town. Here the divi-

sion into two zones is even stronger than in Odazzi’s

later picture and the scene is set against an open arch

25 This connection has not been noticed by scholars. See D.

Benati, s.v., [in:] V. Fortunati Pietrantonio, Pittura holog-

nese del ’500, II, Bologna 1986, p. 709; A. Z [archi], s.v. [in:] La

pittura in Italia. II Cinąuecento, ed. G. Briganti, II, [Milano]

1988, p. 629.

26 For the Palermo picture see e.g. A. Salin as, Antonio Van

Dyck e il suo ąuadro per la Compagnia del Rosario in S. Domenico di

Palermo (L’Arte, II, 1899), pp. 499—599; E. Larsen, L opera

107

Bologna, San Bartolommeo (from Fortunati Pietrantonio)

motif. The renown of the Sicilian masterpiece of van

Dyck, described by Bellori27, may account for its

impact lasting well into the 18th century, even if the

Flemish master was not recommended as one of the

models listed by Maratti. The motifs of the Rosary

and clouds, taken over in Campora’s drawing, seem

to confrrm this conjecture. The Madonna of the

Rosary painted by the Neapolitan Luca Giordano

(1634—1705) and later copied by Jean-Honore Fra-

gonard (1732—1806)28, with its sprawling Child and

other motifs related to van Dyck, is further evidence

that the van Dyckian layout became known. Towards

the end of the 17th century the attention of Roman

artists may additionally have been attracted to this

altarpiece because another confraternity of the Ro-

sary in Palermo commissioned Maratti to paint

completa di Van Dyck 1613-1626, Milano 1980, pp. 7—8 and 117,

no. 441; C. Brown, Van Dyck, Oxford 1982, pp. 80—81; E.

Lar sen, The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck, 1, Freren 1988, pp.

132—133 and 2, cat. no. 448.

27 Bellori, o. c. (as in n. 14), pp. 651—653.

28 Cf. Abbe de Saint-Non, Yoyage Pittoresąue ou De-

scription des Royaumes de Naples et de Sicile, L, Paris 1781,

after p. 112.

6. Domenico Tibaldi after Lorenzo Sabatini, Madonna and Child

on a Crescent Moon, engraving.

pupil, Cesare Aretusi (1549—1612) used the same

motif in his early altarpiece in Bologna (Fig. 7),

painted c. 1570—157525. However, in these Bolog-

nese works, Mary is ąuite different from the late

Baroąue ones. So even if the CarraccPs art, as we

have already indicated, enjoyed tremendous populari-

ty in Maratti’s circle, the ultimate source of the group

of Madonna and the sprawling Child depicted in the

pictures c. 1700 seems rather to be Anton van Dyck’s

famous Madonna of the Rosary begun in 1624 for the

Confraternity of the Rosary by the church of San

Domenico in Palermo26 (Fig. 8), continued in Genoa

and finished in Flanders in 1627 after the painter’s

flight from the plague-stricken town. Here the divi-

sion into two zones is even stronger than in Odazzi’s

later picture and the scene is set against an open arch

25 This connection has not been noticed by scholars. See D.

Benati, s.v., [in:] V. Fortunati Pietrantonio, Pittura holog-

nese del ’500, II, Bologna 1986, p. 709; A. Z [archi], s.v. [in:] La

pittura in Italia. II Cinąuecento, ed. G. Briganti, II, [Milano]

1988, p. 629.

26 For the Palermo picture see e.g. A. Salin as, Antonio Van

Dyck e il suo ąuadro per la Compagnia del Rosario in S. Domenico di

Palermo (L’Arte, II, 1899), pp. 499—599; E. Larsen, L opera

107