century32. Like Correggio, van Dyck represented

Mary with the Child who leans in the opposite

direction, thus creating a tension. The group is set in

an open semicircular arcade and is flanked by two

groups of saints standing below and gazing at the

holy vision. Correggio’s putto holding saint George’s

attribute, who seems to be coming out of the picture

toward the beholder, finds its counterpart in van

Dyck’s smali boy closing his nose with his hand, who

rushes forward violently out of the scene. This drama-

tic, realistic feature, seemingly incompatible with the

timeless character of a sacra conversazione scene,

appears to be a conventional symbol of epidemy

rather than an episodic, genre-like representation of

a boy avoiding the stench of decaying victims of the

plague in Palermo, as Bellori and Christopher Brown

believe, because the gesture adopted by the boy was

generally considered to prevent one from contracting

the disease33. Both Rubens and van Dyck reduced

the size of figures in relation to architecture in order

to emphasize the Madonna’s distance and van Dyck

replaced the architectural dado under Correggio’s

Mary with clouds replete with angels, one of whom

wreathes the Madonna. In this way the artist, like

Federico Barocci in his Madonna di Senigallia paint-

ed c. 35 years earlier, connected the subject of the

Rosary with that of Assumption34. The latter ob-

yiously reąuired a two-zoned structure.

9. Peter Paul Rubens, Madonna di San Giorgio, copy after the

painting by Correggio. Yienna, Albertina (from Mitsch)

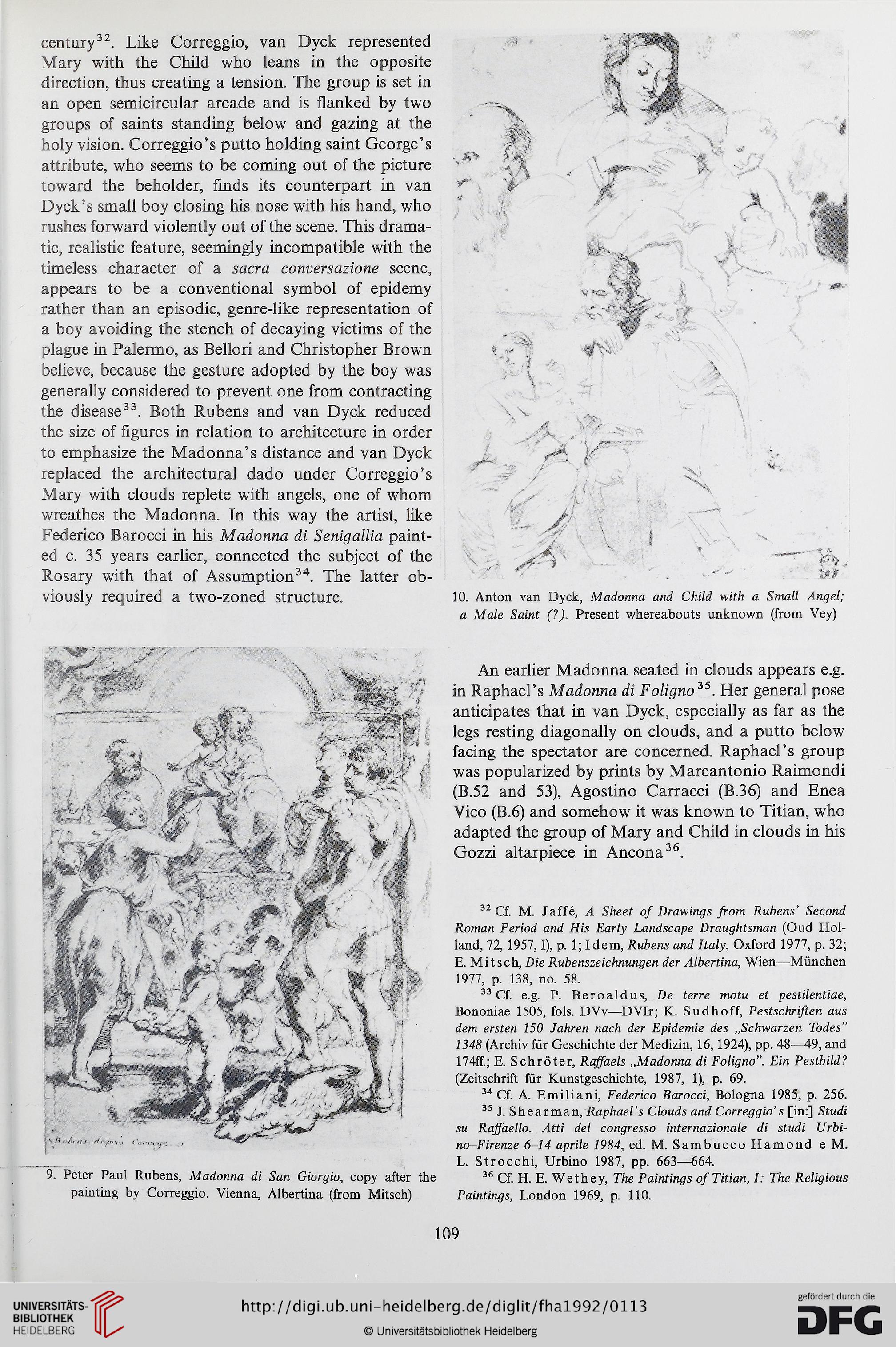

10. Anton van Dyck, Madonna and Child with a Smali Angel;

a Małe Saint (?). Present whereabouts unknown (from Vey)

An earlier Madonna seated in clouds appears e.g.

in RaphaePs Madonna di Foligno35. Her generał pose

anticipates that in van Dyck, especially as far as the

legs resting diagonally on clouds, and a putto below

facing the spectator are concerned. RaphaeTs group

was popularized by prints by Marcantonio Raimondi

(B.52 and 53), Agostino Carracci (B.36) and Enea

Vico (B.6) and somehow it was known to Titian, who

adapted the group of Mary and Child in clouds in his

Gozzi altarpiece in Ancona36.

32 Cf. M. Jaffe, A Sheet of Drawings from Rubens’ Second

Roman Period and His Early Landscape Draughtsman (Oud Hol-

land, 72, 1957,1), p. 1; Idem, Rubens and Italy, Oxford 1977, p. 32;

E. Mitsch, Die Rubenszeichnungen der Albertina, Wien—Munchen

1977, p. 138, no. 58.

33 Cf. e.g. P. Beroaldus, De terre motu et pestilentiae,

Bononiae 1505, fols. DVv—DVIr; K. Sudhoff, Pestschriften aus

dem ersten 150 Jahren nach der Epidemie des „Schwarzen Todes”

1348 (Archiv fur Geschichte der Medizin, 16,1924), pp. 48—49, and

174ff.; E. Schróter, Raffaels „Madonna di Foligno”. Ein Pestbild?

(Zeitschrift fur Kunstgeschichte, 1987, 1), p. 69.

34 Cf. A. Emiliani, Federico Barocci, Bologna 1985, p. 256.

35 J. Shearman, RaphaePs Clouds and Correggio’s [in:] Studi

su Raffaello. Atti del congresso internazionale di studi Urbi-

no-Firenze 6-14 aprile 1984, ed. M. Sambucco Hamond e M.

L. Strocchi, Urbino 1987, pp. 663—664.

36 Cf. H. E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian, I: The Religious

Paintings, London 1969, p. 110.

109

Mary with the Child who leans in the opposite

direction, thus creating a tension. The group is set in

an open semicircular arcade and is flanked by two

groups of saints standing below and gazing at the

holy vision. Correggio’s putto holding saint George’s

attribute, who seems to be coming out of the picture

toward the beholder, finds its counterpart in van

Dyck’s smali boy closing his nose with his hand, who

rushes forward violently out of the scene. This drama-

tic, realistic feature, seemingly incompatible with the

timeless character of a sacra conversazione scene,

appears to be a conventional symbol of epidemy

rather than an episodic, genre-like representation of

a boy avoiding the stench of decaying victims of the

plague in Palermo, as Bellori and Christopher Brown

believe, because the gesture adopted by the boy was

generally considered to prevent one from contracting

the disease33. Both Rubens and van Dyck reduced

the size of figures in relation to architecture in order

to emphasize the Madonna’s distance and van Dyck

replaced the architectural dado under Correggio’s

Mary with clouds replete with angels, one of whom

wreathes the Madonna. In this way the artist, like

Federico Barocci in his Madonna di Senigallia paint-

ed c. 35 years earlier, connected the subject of the

Rosary with that of Assumption34. The latter ob-

yiously reąuired a two-zoned structure.

9. Peter Paul Rubens, Madonna di San Giorgio, copy after the

painting by Correggio. Yienna, Albertina (from Mitsch)

10. Anton van Dyck, Madonna and Child with a Smali Angel;

a Małe Saint (?). Present whereabouts unknown (from Vey)

An earlier Madonna seated in clouds appears e.g.

in RaphaePs Madonna di Foligno35. Her generał pose

anticipates that in van Dyck, especially as far as the

legs resting diagonally on clouds, and a putto below

facing the spectator are concerned. RaphaeTs group

was popularized by prints by Marcantonio Raimondi

(B.52 and 53), Agostino Carracci (B.36) and Enea

Vico (B.6) and somehow it was known to Titian, who

adapted the group of Mary and Child in clouds in his

Gozzi altarpiece in Ancona36.

32 Cf. M. Jaffe, A Sheet of Drawings from Rubens’ Second

Roman Period and His Early Landscape Draughtsman (Oud Hol-

land, 72, 1957,1), p. 1; Idem, Rubens and Italy, Oxford 1977, p. 32;

E. Mitsch, Die Rubenszeichnungen der Albertina, Wien—Munchen

1977, p. 138, no. 58.

33 Cf. e.g. P. Beroaldus, De terre motu et pestilentiae,

Bononiae 1505, fols. DVv—DVIr; K. Sudhoff, Pestschriften aus

dem ersten 150 Jahren nach der Epidemie des „Schwarzen Todes”

1348 (Archiv fur Geschichte der Medizin, 16,1924), pp. 48—49, and

174ff.; E. Schróter, Raffaels „Madonna di Foligno”. Ein Pestbild?

(Zeitschrift fur Kunstgeschichte, 1987, 1), p. 69.

34 Cf. A. Emiliani, Federico Barocci, Bologna 1985, p. 256.

35 J. Shearman, RaphaePs Clouds and Correggio’s [in:] Studi

su Raffaello. Atti del congresso internazionale di studi Urbi-

no-Firenze 6-14 aprile 1984, ed. M. Sambucco Hamond e M.

L. Strocchi, Urbino 1987, pp. 663—664.

36 Cf. H. E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian, I: The Religious

Paintings, London 1969, p. 110.

109