Contemporary Japanese Painting

critics of those days, but principally to the power-

ful influence of the late Mr. Gah5 Hashimoto.

He was originally of the Kano School, but later

originated a new manner of painting and a style

of his own. A man of ideals and aspirations, he

taught both at the Tokyo Fine Art School and

at his own private institution, and thus drew

many new aspirants into the fold of the New

School. He had had a good training in classicism,

and used the new style with proper restraint;

hence he was saved from the production of those

absurd pictures which have sometimes come from

the pencils of inexperienced novices of the school.

Presently clumsy imitators of Gaho's style, in

sheer opposition to that of the Old Schools,

brought out monstrous pictures under cover

of what they called realism or the Occidental

style. This class of crude production was

then joyfully welcomed by younger students

and ill-advised critics, but was never approved

of by the truly artistic instincts of the public.

Foreign students of Japanese art especially

showed little sympathy for these creations,

marred as they were by clumsily imitated

exotic traits, and often secretly remarked with

chagrin, " How in the world can Japanese

painters put their hands to so ungrateful a

task, when they have such excellent classic art

of their own ? " These earlier aspirants of the

New School, in spite of their pretensions to

realism and the Western style, could not, after

all, attain to such excellent naturalistic graces

as were developed generations ago by Hokusai

and Hiroshige.

As already mentioned, the Old Schools are

effete with mannerism, while the New School

has been running into wild eccentricity. In

truth, for the last twenty years or so, there

have been produced no Japanese paintings

worthy of the name. Judging from the present

state of things, the Old Schools, as they are

now understood, seem to be already in the

last stage of decadence with no possible hopes

of recovery. And this is not to be wondered

at, when it is known that the Old-School

painters of the present day, while pretending

to have fathomed the secrets of our classic

art, have not really dipped into its very heart

and spirit. On the other hand, the New

School has failings of its own which cannot

be tolerated, but it commends itself to our

hearty approbation so far as it attempts to

approach closer to nature and to develop art

in keeping with the progress of learning and

knowledge. Its aspirations are good and right,

but it has erred in its choice of means wherewith

to accomplish its ends. And this is why the

New School has not been able to produce works

worthy of consideration.

The rivalry between the Old and the New

Schools is a singular phenomenon in the artistic

society of Japan to-day.

Again, contemporary Japanese paintings may be

distinguished from the point of view of their local

relations. Artistically speaking, Tokyo is one

centre and Ky5to is another. With the advan-

tages of artistic culture under the generous patron-

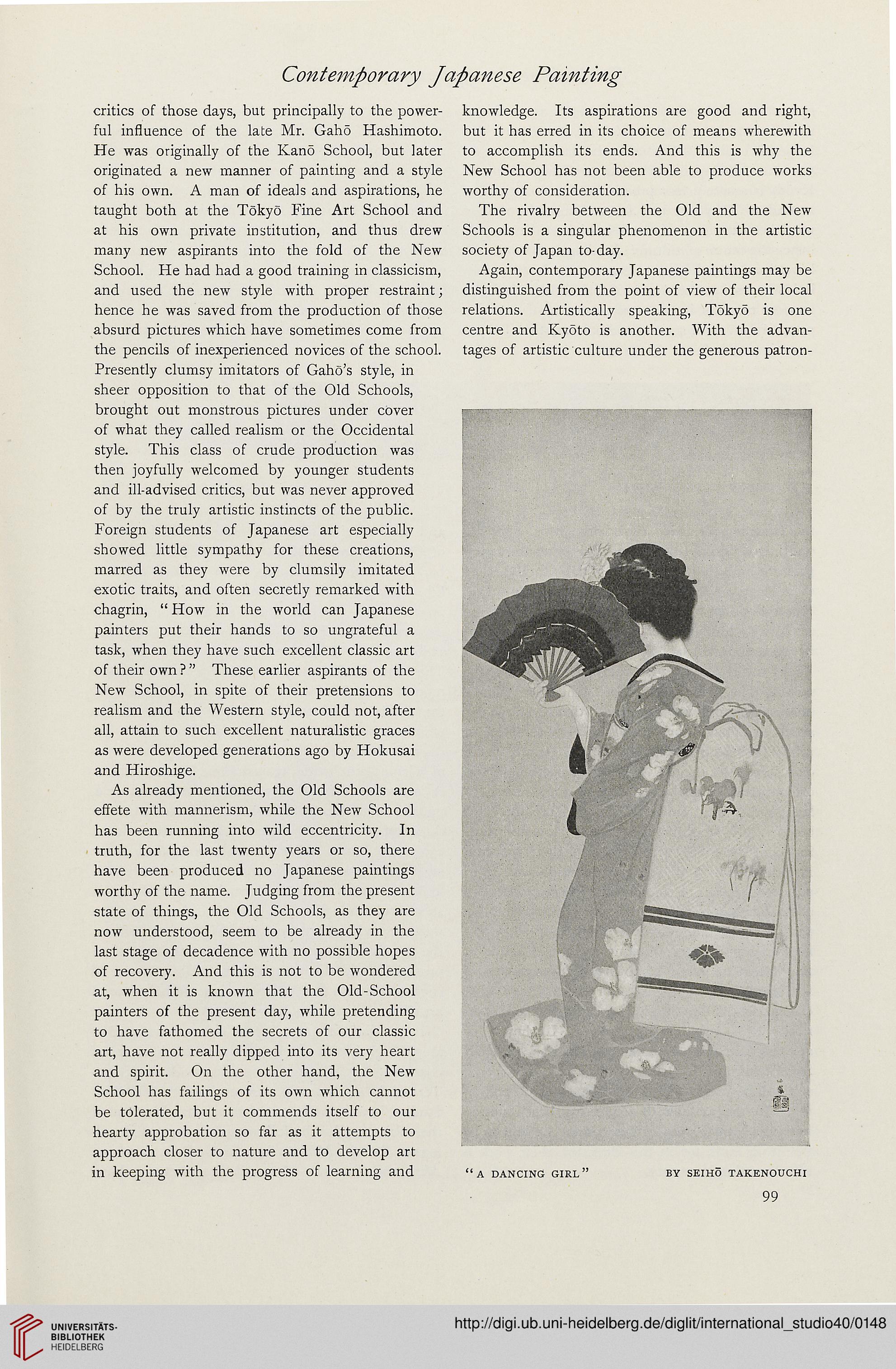

"a dancing girl" by seiho takenouchi

99

critics of those days, but principally to the power-

ful influence of the late Mr. Gah5 Hashimoto.

He was originally of the Kano School, but later

originated a new manner of painting and a style

of his own. A man of ideals and aspirations, he

taught both at the Tokyo Fine Art School and

at his own private institution, and thus drew

many new aspirants into the fold of the New

School. He had had a good training in classicism,

and used the new style with proper restraint;

hence he was saved from the production of those

absurd pictures which have sometimes come from

the pencils of inexperienced novices of the school.

Presently clumsy imitators of Gaho's style, in

sheer opposition to that of the Old Schools,

brought out monstrous pictures under cover

of what they called realism or the Occidental

style. This class of crude production was

then joyfully welcomed by younger students

and ill-advised critics, but was never approved

of by the truly artistic instincts of the public.

Foreign students of Japanese art especially

showed little sympathy for these creations,

marred as they were by clumsily imitated

exotic traits, and often secretly remarked with

chagrin, " How in the world can Japanese

painters put their hands to so ungrateful a

task, when they have such excellent classic art

of their own ? " These earlier aspirants of the

New School, in spite of their pretensions to

realism and the Western style, could not, after

all, attain to such excellent naturalistic graces

as were developed generations ago by Hokusai

and Hiroshige.

As already mentioned, the Old Schools are

effete with mannerism, while the New School

has been running into wild eccentricity. In

truth, for the last twenty years or so, there

have been produced no Japanese paintings

worthy of the name. Judging from the present

state of things, the Old Schools, as they are

now understood, seem to be already in the

last stage of decadence with no possible hopes

of recovery. And this is not to be wondered

at, when it is known that the Old-School

painters of the present day, while pretending

to have fathomed the secrets of our classic

art, have not really dipped into its very heart

and spirit. On the other hand, the New

School has failings of its own which cannot

be tolerated, but it commends itself to our

hearty approbation so far as it attempts to

approach closer to nature and to develop art

in keeping with the progress of learning and

knowledge. Its aspirations are good and right,

but it has erred in its choice of means wherewith

to accomplish its ends. And this is why the

New School has not been able to produce works

worthy of consideration.

The rivalry between the Old and the New

Schools is a singular phenomenon in the artistic

society of Japan to-day.

Again, contemporary Japanese paintings may be

distinguished from the point of view of their local

relations. Artistically speaking, Tokyo is one

centre and Ky5to is another. With the advan-

tages of artistic culture under the generous patron-

"a dancing girl" by seiho takenouchi

99