Mr. Robert Anning Bell

sion behind an image of the Virgin. Almost like Diirer and Leonardo, both with the genius of

by accident we get here in miniature the science to embarrass their genius for art, attempted

issues of the Italian Renaissance ; and this is to explain, instead of going on with their work,

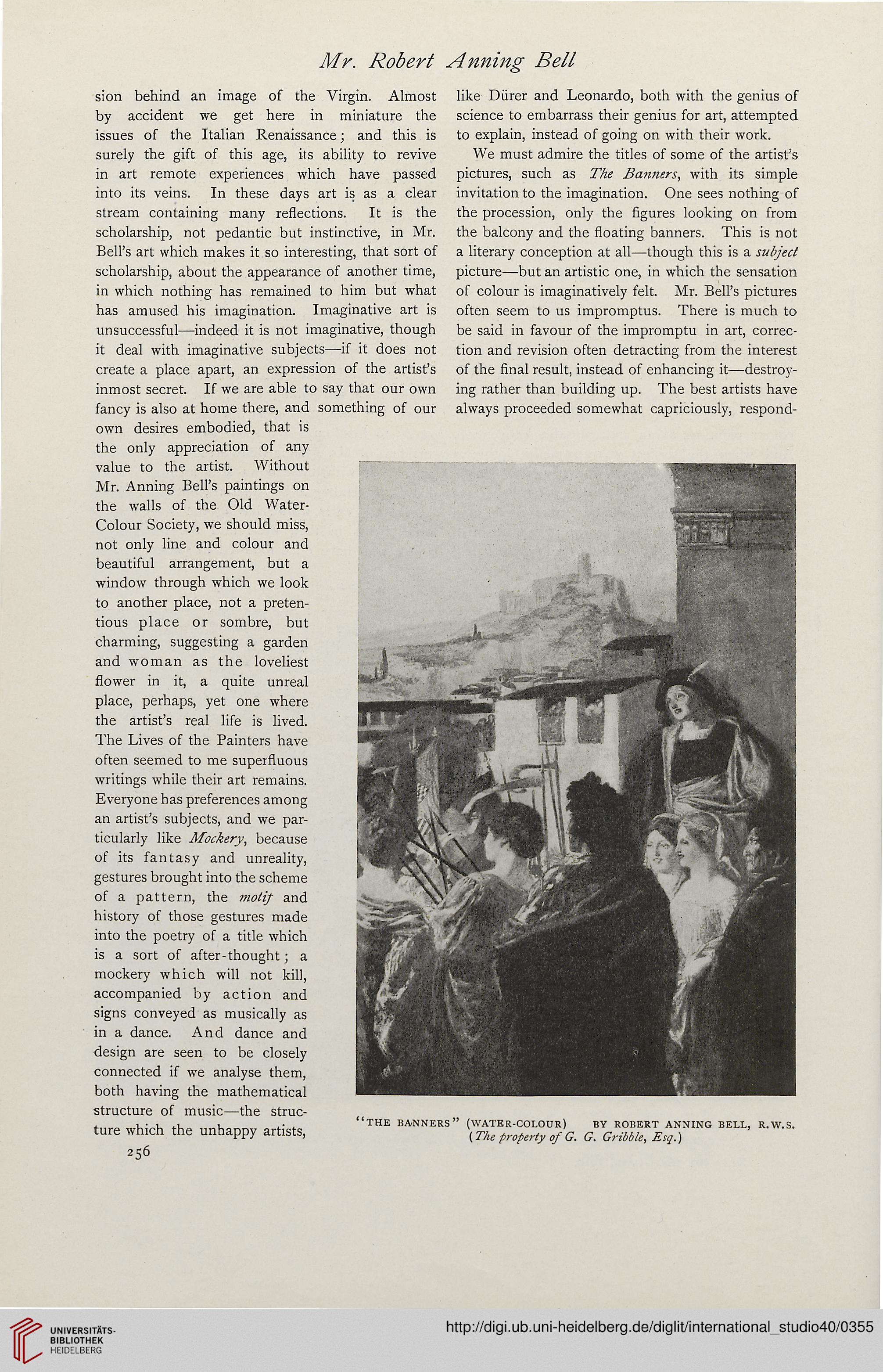

surely the gift of this age, its ability to revive We must admire the titles of some of the artist's

in art remote experiences which have passed pictures, such as The Banners, with its simple

into its veins. In these days art is as a clear invitation to the imagination. One sees nothing of

stream containing many reflections. It is the the procession, only the figures looking on from

scholarship, not pedantic but instinctive, in Mr. the balcony and the floating banners. This is not

Bell's art which makes it so interesting, that sort of a literary conception at all—though this is a subject

scholarship, about the appearance of another time, picture—but an artistic one, in which the sensation

in which nothing has remained to him but what of colour is imaginatively felt. Mr. Bell's pictures

has amused his imagination. Imaginative art is often seem to us impromptus. There is much to

unsuccessful—indeed it is not imaginative, though be said in favour of the impromptu in art, correc-

it deal with imaginative subjects—if it does not tion and revision often detracting from the interest

create a place apart, an expression of the artist's of the final result, instead of enhancing it—destroy-

inmost secret. If we are able to say that our own ing rather than building up. The best artists have

fancy is also at home there, and something of our always proceeded somewhat capriciously, respond-

own desires embodied, that is

the only appreciation of any

value to the artist. Without

Mr. Anning Bell's paintings on

the walls of the Old Water-

Colour Society, we should miss,

not only line and colour and

beautiful arrangement, but a

window through which we look

to another place, not a preten-

tious place or sombre, but

charming, suggesting a garden

and woman as the loveliest

flower in it, a quite unreal

place, perhaps, yet one where

the artist's real life is lived.

The Lives of the Painters have

often seemed to me superfluous

writings while their art remains.

Everyone has preferences among

an artist's subjects, and we par-

ticularly like Mockery, because

of its fantasy and unreality,

gestures brought into the scheme

of a pattern, the motif and

history of those gestures made

into the poetry of a title which

is a sort of after-thought; a

mockery which will not kill,

accompanied by action and

signs conveyed as musically as

in a dance. And dance and

design are seen to be closely

connected if we analyse them,

both having the mathematical

structure of music—the struc-

, A ~U„ H t "THE MANNERS" (WATER-COLOUR) BY ROBERT ANNING BELL,

ture which the unhappy artists, (The property of G G Gribb^ Esq )

256

sion behind an image of the Virgin. Almost like Diirer and Leonardo, both with the genius of

by accident we get here in miniature the science to embarrass their genius for art, attempted

issues of the Italian Renaissance ; and this is to explain, instead of going on with their work,

surely the gift of this age, its ability to revive We must admire the titles of some of the artist's

in art remote experiences which have passed pictures, such as The Banners, with its simple

into its veins. In these days art is as a clear invitation to the imagination. One sees nothing of

stream containing many reflections. It is the the procession, only the figures looking on from

scholarship, not pedantic but instinctive, in Mr. the balcony and the floating banners. This is not

Bell's art which makes it so interesting, that sort of a literary conception at all—though this is a subject

scholarship, about the appearance of another time, picture—but an artistic one, in which the sensation

in which nothing has remained to him but what of colour is imaginatively felt. Mr. Bell's pictures

has amused his imagination. Imaginative art is often seem to us impromptus. There is much to

unsuccessful—indeed it is not imaginative, though be said in favour of the impromptu in art, correc-

it deal with imaginative subjects—if it does not tion and revision often detracting from the interest

create a place apart, an expression of the artist's of the final result, instead of enhancing it—destroy-

inmost secret. If we are able to say that our own ing rather than building up. The best artists have

fancy is also at home there, and something of our always proceeded somewhat capriciously, respond-

own desires embodied, that is

the only appreciation of any

value to the artist. Without

Mr. Anning Bell's paintings on

the walls of the Old Water-

Colour Society, we should miss,

not only line and colour and

beautiful arrangement, but a

window through which we look

to another place, not a preten-

tious place or sombre, but

charming, suggesting a garden

and woman as the loveliest

flower in it, a quite unreal

place, perhaps, yet one where

the artist's real life is lived.

The Lives of the Painters have

often seemed to me superfluous

writings while their art remains.

Everyone has preferences among

an artist's subjects, and we par-

ticularly like Mockery, because

of its fantasy and unreality,

gestures brought into the scheme

of a pattern, the motif and

history of those gestures made

into the poetry of a title which

is a sort of after-thought; a

mockery which will not kill,

accompanied by action and

signs conveyed as musically as

in a dance. And dance and

design are seen to be closely

connected if we analyse them,

both having the mathematical

structure of music—the struc-

, A ~U„ H t "THE MANNERS" (WATER-COLOUR) BY ROBERT ANNING BELL,

ture which the unhappy artists, (The property of G G Gribb^ Esq )

256